When Nathan Graeser [MDiv ’12] and his buddies joined the Indiana National Guard straight out of high school, they didn’t think there was much of a chance they’d see combat. National Guard troops hadn’t been called since World War II. After a year of training, Nate enrolled as an undergraduate at Indiana University.

His second day of college was September 11, 2001.

Nate and his unit went on alert after the terrorist attacks that became known simply as “9/11,” ready to be deployed at any time—but for months on end, they weren’t. As freshman year turned to sophomore year, Nate decided to sign up for officer training and encouraged his best friend, Brett, to do the same. “Nah,” Brett replied: “I think I’ll get out of the military altogether.”

He didn’t get out in time. Two weeks later, their unit got the call. All were deployed to Afghanistan—except for those in officer training. Nate stayed in Indiana and said goodbye to his friends.

Brett didn’t come back. A few months before his slated release, he was killed by a landmine. The news rocked Nate’s world. “It was devastating. I lost my best bud,” he says. Almost as devastating was what he saw in his other friends who did make it back.

“They were absolute wrecks,” he says. “These guys had just been in combat for a year—but they got off the plane back home and there was no one to help them with that transition. Wives left them. They started getting DUIs. I was meeting with them, having coffee after coffee, listening and doing all I could to help, but it was like trying to stop a flood. I remember thinking, why am I the only one doing this?”

What you’re doing, Nate’s friends told him, is what chaplains do. This, along with a vivid call that came to him in a dream, convinced Nate to pursue chaplaincy and, as preparation, study at Fuller. Completing his MDiv in 2012, he became a chaplain soon after for the California Army National Guard 1-144 Field Artillery Battalion.

It wasn’t long, however, before Nate realized he needed more equipping. “One of my first days as a chaplain I saw a guy who was suicidal,” he remembers, “and I thought: ‘I don’t have the full skill set to deal with this.’ At Fuller I’d built a theological framework and understanding of suffering—I knew how to be present, to listen, to pray—but felt like I needed more tools to concretely apply what I’d learned in seminary.” He found those tools in a new military social work program at USC, which he completed over the following year. “Fuller was the ‘why,’ and USC was the ‘how,’” he says, explaining that the two programs complemented each other and prepared him to help veterans in a more fully orbed way.

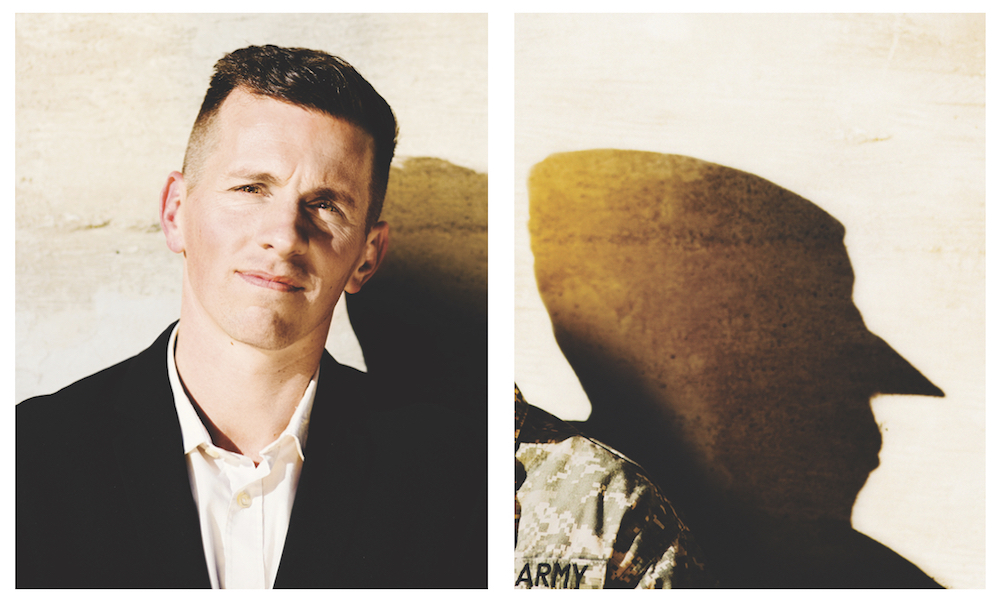

Bringing together that seminary and social work training, Nate today lives, as he puts it, “in two worlds.” He dons his military uniform monthly to serve as chaplain to the 450 soldiers in his National Guard unit. The rest of the time he dons a suit jacket for his civilian job: as Community Program Administrator for USC’s Center for Innovation and Research on Veterans and Military Families, where he works to catalyze support for veterans across the Los Angeles area.

Unifying those seemingly diverse worlds is Nate’s fierce conviction that every struggling veteran needs the support of a community. Far from the one-man counseling center he was to his veteran friends back in Indiana, Nate now pours his heart into rallying and equipping others to come together and do what he couldn’t do alone.

MORAL INJURY AND THE COMMUNALIZATION OF GRIEF

In the course of his studies at USC, Nate came across the concept of “moral injury,” coined by psychiatrist and author Jonathan Shay, to describe the deep wounds that result when one has been involved in actions that violate his or her own moral code. The discovery was an “aha” moment for Nate: “It gave me language to describe what I had been seeing and talking about for a long time as both a chaplain and a social worker.

“You can treat the symptoms of PTSD clinically and medically, but moral injury encompasses the soul wounds that linger,” he says. “Soldiers need to accept and forgive themselves, and that’s a long, hard process.” Nate sees moral injury as a holistic way of understanding the suffering veterans carry—and sees the community, especially the faith community, as having a responsibility to help address it.

“When people are pulled from their community and sent to war, the community should help own the suffering they bring back with them,” he says. “That kind of pain is not meant to be borne alone. Veterans can’t make sense of it alone. They need others to come alongside them, to listen to their stories, to help hold their pain so they can deal with it.”

Shay calls this the “communalization of grief,” and one way to reinforce it, says Nate, is through ritual. One particularly meaningful one Nate leads is what he calls “the Warrior Circle” [more details below], in which both veterans and civilians gather to consider the impact of soldiers leaving for war and then returning to their communities, marking one another with ash to signify the internal and external wounds of battle all are called to bear together.

“You can agree or disagree with whether war is justified,” Nate says, “but either way there is a duty to heal, especially among the faith community. To me this is a form of peacemaking. How can you make peace without dealing with the thing that’s the antithesis of peace—war—and the wounds that result from it?”

BECOMING THE BEST PASSERS WE CAN BE

Nate’s work is broad as well as deep: encouraging communities not only to understand and share in veterans’ invisible burdens, but also to reach out with more visible forms of practical support—a primary focus of his day job at USC. In that world he oversees the Los Angeles Veterans Collaborative, a network of more than 250 organizations and stakeholders seeking together to identify and resolve the needs of local veterans.

Gathering monthly in downtown Los Angeles, those stakeholders include anyone who wants to come with an idea or service that might help veterans. At a recent meeting, the opening announcements revealed just how diverse those voices can be. Some offered traditional forms of help—employment, housing, legal aid—but others were more inventive: culinary arts classes, dance and music workshops for families, a compassion fatigue group. “We have 20 to 30 new people coming every month,” says Nate. “My goal is to build social capital around vets’ needs. Every time you see a responsive, effective program, there’s an engaged community behind it.”

Working groups that focus on different areas of interest foster brainstorming and pilot programs. One outcome is Text2Vet, a 24-hour service where veterans can connect, via text, with a peer veteran navigator who links them to the resources they need. Another is expanding a Meals on Wheels outreach so that, when volunteers deliver food to vets, they also conduct a wellness check—seeing how the vet is doing, monitoring medications, referring to other services.

It’s the “referring to other services” that’s fundamental to Nate. “We can support veterans much more holistically when we make those connections,” he says, finding an analogy in pro basketball point guard John Stockton. “The guy made NBA records for the most assists. He helped his teammates shine because he was such a great passer. We all need to be the best passers we can be.”

Nate brings this approach to his chaplaincy work as well. “Only about 20 percent of what I do there is what people think of as classic chaplaincy: praying with the soldiers, holding services and Bible studies. Mostly it’s soldiers coming to me with employment, family, life issues—and whenever I can, I connect them to someone in the community who can help them take the next step they need to take. We don’t separate our everyday lives from our spiritual lives.”

KEEPING THE LONG VIEW

As he does the work of helping to make Los Angeles a kinder place to its veterans, Nate looks to two Fuller professors who were particularly formative. The late ethics professor Glen Stassen modeled an approach that didn’t shy away from seemingly intractable challenges. “He tried to take on the world,” Nate recalls. “He was always asking hard questions—about homosexuality, about war. He showed us that we can actually bite off really complex issues, get at the root problems, talk about ways to solve them.” Pastoral counseling professor David Augsburger helped Nate grasp the deeply permeating influence of family and community systems: “None of us makes decisions completely objectively; others’ choices affect us tremendously. We’re interconnected, each a piece of a larger system.”

As he does the work of helping to make Los Angeles a kinder place to its veterans, Nate looks to two Fuller professors who were particularly formative. The late ethics professor Glen Stassen modeled an approach that didn’t shy away from seemingly intractable challenges. “He tried to take on the world,” Nate recalls. “He was always asking hard questions—about homosexuality, about war. He showed us that we can actually bite off really complex issues, get at the root problems, talk about ways to solve them.” Pastoral counseling professor David Augsburger helped Nate grasp the deeply permeating influence of family and community systems: “None of us makes decisions completely objectively; others’ choices affect us tremendously. We’re interconnected, each a piece of a larger system.”

Though he didn’t yet know, while he was at Fuller, the extent of the work he’d be doing today, Nate says seminary helped shape him for it. “My experience at Fuller cemented in me the desire and willingness to take on the grand challenges that require a long-haul approach,” he says. “The easy problems have been solved. It’s the hard ones that are left. We have to know we won’t fix this today or even tomorrow, but with thoughtful, loving action over time, we can see real change.”

THE WARRIOR CIRCLE

Thoughtful rituals can help communities better understand and share in the moral injury—soul wounds—many veterans bear. Nate Graeser developed the Warrior Circle ceremony, briefly described below, as one such ritual he often leads in faith community contexts.

Those who have served in the military form a circle, with civilians forming a circle around them—signifying that servicemembers begin within a community that knows them. The servicemembers are then asked to walk away, passing between the civilians to go beyond the large circle, symbolizing their deployment. The civilians can no longer see them or connect with them.

Once outside the circle, an appointed “chief” marks the forehead of each servicemember twice with ash. The first stripe signifies the visible sacrifices and wounds of battle: the physical disabilities and health challenges many veterans carry back from war. The second stripe symbolizes the invisible wounds they take on: birthdays, anniversaries, and other special moments they’ve missed back home; relationship losses; moral and psychological injuries.

Veterans then move back inside the circle, signifying the end of their deployment. Civilians are called to notice how they must step aside to let the veterans back in, and to notice how they now look different, marked with ash. The veterans then, in turn, mark each civilian with one stripe as well—for the invisible wounds they are called to bear along with their veterans.

Finally, all are called to notice that they are back in the formation in which they began, yet there is a difference. Every individual shows the marks of battle. Some may carry more stripes, but all share in the sacrifices and burden of war.