For many congregations, the coffee hour after church has become like the Thanksgiving dinner episode of a sitcom. Everyone knows that they love each other, but the only way to keep the peace is to make sure no one discusses politics. Many of our churches have good Christians on very different sides of the political issues. And the rhetoric of the time has come to treat politics like a college football rivalry—rooting for my team means booing your team.

For many congregations, the coffee hour after church has become like the Thanksgiving dinner episode of a sitcom. Everyone knows that they love each other, but the only way to keep the peace is to make sure no one discusses politics. Many of our churches have good Christians on very different sides of the political issues. And the rhetoric of the time has come to treat politics like a college football rivalry—rooting for my team means booing your team.

According to a recent Pew Research study, 55 percent of Republicans view Democrats as “more immoral” than other Americans, while 47 percent of Democrats say the same about Republicans.1 We Christians are called to the kind of community that listens intently to one another with love and respect. We are called, at the same time, to engage the world in such a way that we cannot ignore the political sphere—especially since so many of today’s political debates are framed in moral and religious terms.

How, then, do we maintain the bonds of faith in such a divided climate?

We interviewed four pastors who lead at churches with people on both sides of the political divide. We asked them, as they look to the coming election year, four questions about how they think about Christian unity in the midst of political division. Here are their answers.

How do you, as a pastor, help your people remain the community of faith in the midst of these tense times and in this fractious world?

Suzanne Vogel: One of the first questions I have to answer is, “What is our call as a church? What is my call in relationship to the culture and the politics of this moment? How can we be a prophetic voice?” There are different ways churches can answer that question. Some churches and some pastors are invited by God to be a prophetic voice that calls their congregation into a particular view that leans politically more in one direction or another. Personally for me, and historically for our church, the prophetic voice we’re called to is to actually press against the tribalism of the moment and call the church to lay down our political differences and align with the kingdom first. We are in a culture where we don’t know how to hold covenant anymore. If I disagree with you, I’m out—I unfriend you on Facebook and I mute you on Twitter and I watch only my news shows and I get a divorce and I move towns. It’s systemic. So the most prophetic voice we can have is to actually demonstrate the gospel in the midst of our differences. That’s the kind of discipleship we want to cultivate, that practice of living the character of the gospel, even in our differences.

Phil Allen: I have people who are left. I have people who are center. And I have people who are right. But I ask people to think about where their allegiance is. And why they believe what they believe. It’s about getting people to look at their political allegiances, their cultural allegiances, denominational, what have you, then filtering them through the lens of Scripture. That can be tricky, too, because people are looking for the one-to-one equivalents. The verse that says that thing. So it’s about teaching people to have a biblically informed theological lens, and also an imagination, because you might not find a verse that talks about that thing. Also, it’s about getting people to have conversations within our ministry, giving a space where they can share perspectives, whether they walk away agreeing or not. It’s about having the willingness to sit and hear someone else’s perspective.

Andrés Zelaya: Part of being a pastor is that my people expect me to show them what it means to be a Christ-centered, peaceful, calm, focused presence in their midst. So a big task, for me, is making sure that I choose words carefully, making sure that the way I talk about politics or even certain positions is firm and with conviction, but full of grace. Full of charity toward those who disagree with me. A big part of being a pastor to my community of faith is making sure they have some model or example to show them what it looks like to navigate the tensions that do exist in our country. During lunches or coffee meetings, when somebody inevitably brings up a certain position or candidate, maybe starts describing them in an uncharitable tone, I try shifting the tone of the conversation. Ultimately I want to model Jesus, and that means thinking, how would Jesus respond in this situation? What would he act like? What would he say? I’m trying to think really critically in that moment and just be charitable toward others’ opinions and positions.

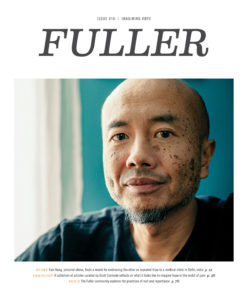

Kevin Haah: It’s helped me to teach my congregation about how the gospel has three parts—incarnational, restoration, and atonement—which each has a different understanding of the kingdom of God. The incarnational aspect warns us against making too much of political engagement. The kingdom of God and the kingdom of this world are different, and Jesus did not focus on overthrowing the kingdom of this world. This aspect of the gospel focuses more on creating a countercultural community that reflects the kingdom of God and loves our neighbors. The restoration aspect of the gospel calls us to a more transformational approach to community and political engagement. We are in what theologians say are the “in-between times.” But Jesus gives us the end picture of what the kingdom of God looks like—the New Jerusalem. (That’s where our church—New City—got its name.) It is a place where all people from all cultures come together. It is a place where there is no more injustice. No more racism. No more sexism. It is a place where there is no more pollution or decay, and no more poverty or sickness. It is a dwelling place of God. When you know what the kingdom is supposed to look like, you know what you are supposed to do now. So we are called to engage the world and help the poor, marginalized, orphans, widows, immigrants, oppressed, suffering, sick, and otherwise excluded people. Finally, the atonement aspect of the gospel reminds us that it is not just about compassion and helping the needy or social justice. The Bible teaches us that Satan has taken over the world—not just our hearts, but also the systems of this world. The world is broken at all levels. This is why we need the cross. Jesus, by dying on the cross, liberated us from bondage to sin. Grace has the power to change people’s hearts. And it is through changing people’s hearts that we can truly see change in the world.

Are there any political issues that you feel you absolutely must address? Or any political issues you feel like you absolutely must not address?

Phil: There’s no political issue that I feel like I can’t address. There’s none that I won’t address. None I’m afraid to address. I do think the pro-life, pro-choice debate is one that I should address. I don’t even address it to try to convince people anymore. I just address it to try to help people be informed, and to see it through a biblically informed theological lens. Where they land is totally up to them. Also, I think the issue of power, as it relates to race, socioeconomic status, gender—those things have to be talked about. Power is the undercurrent to a lot of issues. It’s power dynamics. A lot of the time, they are longstanding and they’re unchallenged. So, when I get a chance, I’ll talk about that to get people to start to see below the surface and reflect more deeply about, what’s really happening when this politician says this? Or when this party does this thing, what’s really happening? What’s at play here?

Andrés: If the kingdom of God is truly here, and if Jesus inaugurated the kingdom and he rules and is sovereign over all things, there’s not a single domain, area, or issue in life that Christians are not empowered or called into. Now, as a pastor, as a shepherd who knows my people, it requires wisdom and discernment to know how to talk about certain issues in a way that makes sense, that’s contextualized, that’s graceful, that’s truthful and honest. For us here, being the fourth-largest city in America, issues around the economy must absolutely be addressed. Issues around racial segregation, sure. Issues around social class dynamics, yeah. Issues around immigration and diversity, absolutely. I think those have to be addressed. Now, do they necessarily have to be addressed from the pulpit, or with the same level of force or intention? Not necessarily. That’s where tact and wisdom, just trying to be a good shepherd to my people, comes in.

Suzanne: We try to preach the Scripture and let the issues come out of it, rather than bringing the issue to the Scripture. I think that keeps us from being reactive and it allows us to respond over time. And the truth is, if you spend much time in the Bible, there are issues that get raised all over the place. Where things get tripped up in the congregation is if they feel like we’re bringing an agenda to the Scripture. However, I would say issues of race and racism are pretty important to us because we’re an interracial body. We’re for sure trying to address that and touch it and deal with it. The hard part right now is that you could be reacting every single Sunday. Every single Sunday, you could be reacting to something and commenting on something that’s happened. I just feel like the culture’s baiting us into that all the time.

Kevin: I don’t want to be afraid to speak up prophetically on issues that affect the least among us. If we don’t stand with the oppressed, who will? If we don’t stand with the refugees, who will? If we don’t stand with those who are victimized, who will? We have to live in the tension between two competing biblical principles: first, that Jesus did not seek to change the world through grabbing the power of this world, even when there was a lot of evil going on from the government; and second, when we truly love people who are oppressed, we are called to find the source of the problem and address it. If people are pushing people off the roof of a building, we can’t just take care of the people who are pushed off. We have to address the issue of the people who are pushing people off. We sometimes need to get the police to go up there and stop the pushers. Or maybe we have to make sure the government policy is not what is pushing people off the building. It’s important not to get pegged into liberal or conservative mode and instead think about the kingdom of God. What does that look like? It may look like a combination of policies supported by Democrats and Republicans or Libertarians.

Are there any role models that you look to? A person who you think is navigating this well?

Suzanne: I think about Eugene Peterson. I’ve realized that I need to be really aware of my own political convictions and desires, and what sparked that for me was in Eugene Peterson’s book Under the Unpredictable Plant. He talks about how one of the temptations of ministry is that we occasionally speak for God, and then we start thinking we always speak for God—or even that we are God. So I have to manage my own humility. Just because I’m the pastor and I happen to have the platform doesn’t mean I get to always speak what I think. I have a position of authority and power that I have to steward carefully.

Andrés: Tim Keller. As far as I’ve seen, he has done a really great job, especially being from a large urban center like New York City. I imagine, being in ministry for almost 30 years there, he’s had tons of these conversations. From the ’80s when he started his congregation, there’s been a ton of different parties, whether it’s in Congress or the presidency or local elections. I’ve really appreciated his tact.

Phil: I really have to go back to Obama. I’m not saying I agree with all of Obama’s policies, but the man that he is, the person he has shown himself to be—I liked the way he carried himself. The way he speaks is calming; it brings people down to think and reflect, and not act so emotionally.

Kevin: I think a good example is Martin Luther King Jr. He didn’t seek to change society through the power of the sword. He sought to change society by demonstrating enemy love, even when they were beaten or blasted with a water cannon.

Are there any Scriptures that call out to you in this moment?

Phil: The first that comes to mind is Ephesians 2. Christ brought the Gentiles and Jews together, reconciled them in his body. I use that when we talk about race, but I think the principle can apply to any division, any divisiveness, that’s going on. Before there’s a reconciliation, there’s a solidarity. His body represents solidarity. He gave of himself on behalf of—for—others. I try to get people to come back to a place of humbly submitting ourselves to listening to the other person, the willingness to be in solidarity with, so that we can be reconciled—so that we can do things together.

Andrés: Recently, the Psalms have allowed me to give language to the different tensions that I often feel in my heart. Whenever there’s an issue or a politician who says something that rubs me the wrong way, to know that you can come before God and there’s nothing that can, or should, remain hidden or veiled. To know that I can, when I see an injustice, speak to God about it and wrestle with it honestly. Even in the midst of my doubts and my questions and my anger. Like Psalm 58, it’s the Psalmist railing against unjust politicians and how they take bribes or how they ignore the cry of the poor. And the cry of the Psalmist is—I mean, we want to label it righteous anger, and it is, but it’s anger nevertheless. The Psalmist is going to God and saying, “God, may they become like the snails who melt under the sun. May they be like a baby who never saw the light.” It’s very strong language. When you’re living in this tension, to know I don’t have all the answers, but I need to have somewhere to bring them to, that’s the Psalms for me. I need to have somewhere to vent my anger, my stress, my sadness, my questions. And to know that God is there, listening.

Kevin: One of the first things Jesus said in public was this, in Mark 1:15: “The time has come. The kingdom of God has come near. Repent and believe the gospel.” Then he went on to demonstrate the power of the kingdom by healing the sick and casting out demons, to teach us what this kingdom was like. It is a place where things are upside-down. The marginalized are elevated. The poor, blind, and oppressed are freed. Sinners are forgiven and embraced. Even enemies are loved. They assumed that the kingdom of God would overpower the kingdom of this world immediately. But Jesus said, no. He said in John 18:36 when he was conversing with Pilate: “My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jewish leaders. But now my kingdom is from another place.” We need the kingdom of this world. We need our police, courts, judges, legislators, governors, and military. But what happens when the church, the visible presence of the kingdom of God on earth, tries to take over the kingdom of this world or to fuse the two kingdoms? Every time we have done that, we have created a huge mess. Christianity has a bad history because it started to wield the power of the sword, the power of the kingdom of this world. But the incarnational aspect of the gospel tells us that we have to be very careful when the church starts to make winning political battles and gaining political power its focus.

Suzanne: Ephesians 3 is all about how Christ, in himself, tears down the dividing wall of hostility. Then, chapter 4 pivots and talks about, “As a prisoner of the Lord, I urge you to live a life worthy of the calling you’ve received.” Most of us would think, well, that life looks like a life of huge sacrifice, maybe, or radical generosity, or mission work in some other part of the country. But then he says, “Okay, this is what it looks like: Be completely humble and gentle, patient, bearing with one another in love, making every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace.” So that’s the rubric I think about a lot and talk about a lot. This is what in Ephesians is defined as a life worthy of the calling we have received.

ENDNOTES