Alumni Delonte Gholston (MDiv ’15) and Justin Fung (DMin ’19) are pastors in Northeast DC, their churches just 15 minutes apart. The two meet occasionally to share their experiences pastoring in the nation’s capital. While the city is often thought of as a stage for national politics, they focus their ministries first on the lived experiences of their communities and the people that fill them. Because DC does not have voting representation in Congress, they point out, political engagement has certain limitations for many DC residents. However, together with their congregations, they engage their neighborhoods and the political circumstances that face them, such as access to education, gentrification and displacement, and police violence. Here are two stories of pastors whose ministries don’t avoid politics—rather, their political engagement is from the ground up. It begins with the streets, schools, homes, and people that make up their communities.

Delonte

Delonte

On the evening of September 27, 2019, the DC Peace Walk was scheduled in a Washington, DC neighborhood that had recently received notice that their homes would be torn down. As dusk fell, friends and neighbors sat outside talking with one another as kids ran around and climbed on the jungle gym at the neighborhood playground. While they played, a police SUV drove back and forth on the street, bright white lights shining from its roof onto friends gathered and into their living rooms—a constant traumatizing reminder of violence. Before officially beginning the peace walk, which would be a time to meet neighbors and share job and health resources, Delonte Gholston, known in his community as Pastor Delonte, lifted his hands and prayed: “We’re here because of a collective trauma. We’re all survivors of violence in some way. We’re here to say no to violence. We’re here to say yes to love.”

Saying Pastor Delonte grew up in DC may give the wrong impression if it leads to imagining large white monuments and people in suits chauffeured in motorcades with tinted windows. Those images of the nation’s power do not represent Northeast DC, where Delonte now pastors, a predominantly Black area of the city 15 minutes east of the US Capitol Building. The tightly packed rows of two-story brick houses and apartments are full of families and friends, the neighborhood alive with people walking, talking, and living. But conspicuously missing are the grocery stores, restaurants, and businesses that mark the wealth and resources pooled into other DC neighborhoods down the road.

Pastor Delonte was raised in Northwest DC by parents who fled the racist terrorism of the deeper South and lived in a city that still felt the warmth of the civil rights era fire. “You know, I grew up when Marion Barry was the mayor, almost my whole childhood—the former chair of SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee]. Our shadow-elected congressman was Walter Fauntroy, the man who helped to organize the March on Washington.”

As a child, Delonte learned from the leaders of the civil rights movement, even performing their speeches under the eye of the pastor-activists who helped lead the movement. “When I was six years old, I was memorizing King speeches. My dad was really into King and X. He would have me listening to vinyls and I would memorize them.” Pastor Delonte remembers that, the second year that Martin Luther King’s birthday was celebrated as a holiday, “All the Black churches around the city were trying to figure out what to do. So they had a bunch of us do different things and I did my King speech. And then somebody else there was like, ‘You should do that speech at this other thing.’ So I did my speech at Israel Baptist Church, which is a big church in Northeast DC. And Wyatt Tee Walker was there, who was Dr. King’s correspondence secretary—was like his right-hand man. I’ll never forget it.”

At the same time, DC was experiencing turmoil. The arrival of crack cocaine, increased police surveillance and harassment, and violence all came as a package in the ’80s for many Black communities, including those in the nation’s capital. “Growing up in this city, the power of the nation has always been centered here, but the resources of the nation have never made their way here.”

Even though Pastor Delonte felt that church provided a sanctuary for him through his childhood, it did not stop him from experiencing the trauma happening in the neighborhood. “I still saw everything everybody else saw, still heard everything everybody else heard. Still saw people bleed out. I mean, I have tons of friends who have been killed. Still pulled over by police, harassed. For different things like having an air freshener hanging from my mirror, being pulled over because it’s an obstruction to my view.”

A tradition and memory of Black church resistance, along with a community burdened by violence, led Pastor Delonte to search for prophetic fire—the fire that led the church of the 1960s to resist the political realities crushing the marginalized. To him, even churches with histories of political resistance seemed to have lost the fire. “I guess it’s just been a lifelong kind of query, or a lifelong quest—what happened to the prophetic fire? What happened to Wyatt Tee Walker’s fire? What happened to that generation’s fire?”

“As a Progressive National Baptist, I really felt like that was where I was coming from,” says Pastor Delonte. “But I didn’t really see as much of that on the ground. And it wasn’t until I went into the belly of the beast at Fuller that I learned the roots of our own white supremacist theology.” As a student studying the white Euro-American traditions of theology that provide the foundation of evangelicalism, he says he began to realize, “So this is where we get this problematic theology from.”

The search for the Spirit, for the fire of the civil rights movement, led Pastor Delonte into the Black Lives Matter movement. A turning point came for him one day during a demonstration outside of Los Angeles City Hall. “A few of us had been showing up in BLM spaces for quite a while. People knew we were pastors and somebody asked me if I sang,” he remembers. He brought out his guitar and asked, “Does anybody know ‘There’s Power in the Name of Jesus?’ This sister who hadn’t been in church in over a year said, ‘Oh yeah! That’s my song!’ And this brother named Amari, he said, ‘Oh I love that song! That’s my song!’ And Amari is Black, experiencing homelessness in downtown LA, and a strong believer. He followed the Spirit where it led him. And we followed the Spirit where it led. And we were together outside the city hall. And we just sang, ‘There’s power in the name of Jesus to break every chain.’ And that’s where I discovered, I realized—oh my goodness, these are our people.”

Pastor Delonte was able to recognize the Spirit and the Spirit’s people on the street because of the prophets of the Old Testament. “I guess that was one of the gifts of John Goldingay’s class,” he says. “He didn’t have us read a whole bunch of people; he just had us read the prophets. And what really struck me about the prophets was that many, many prophets were really outside the temple courts. Many kings really just wanted to hear from good-news prophets.”

Reflecting on that element of prophetic history in the Old Testament, Pastor Delonte sees a similar pattern today. “When it comes to the movement for Black lives,” he says, “what I learned is that the answer to my question of, ‘What happened to the Spirit of the movement?’ was that it jumped over the church because the church wasn’t willing to continue to be part of it.”

When Pastor Delonte and his family moved back home to DC to pastor Peace Fellowship Church, he knew to search for the Spirit and the Spirit’s people on the streets. Every other week over the summer, Peace Fellowship Church, along with other local churches, met on the streets to walk, to meet neighbors, and to build peace by providing information on job and health services. These were gatherings of God’s people on the streets, a testimony of peace in neighborhoods that suffer what seems to be endless violence.

At the Peace Walk on September 27, Pastor Delonte approached the police vehicle that had been patrolling the area, shining bright lights onto the people after dark, and asked the officers to consider how their surveilling presence might retraumatize the community. Advocating and caring for the community, Delonte serves as a pastor on the street, and all those who join the DC Peace Walks also pastor on the streets as they talk with neighbors, attending to their needs.

The search for the Spirit, the search for the fire, led Pastor Delonte to the streets, where he found the Spirit already interacting with the community, attending to its daily realities and caring for its trauma. What he learned from the Old Testament prophets, and from his work in LA, continues to give direction to his ministry in DC as a pastor of the streets. “What does Genesis chapter 4 say? Genesis chapter 4 says that when Abel was killed, that the blood cried out from the ground,” he says. “The streets are sacred. Where blood is shed is sacred ground.”

Justin

Justin

At noon on Sunday, pastor Justin Fung leads the voices of his church in a final chorus. As the last chords are strummed, a new rhythm takes its place. Bodies all over the room begin to move chairs, fold curtains, and wrap cables. In a few moments, the place where Justin and his congregation gathered for the cup and bread becomes once again the place where children will gather for lunch on Monday. Christ City Church, where Justin serves as a pastor, meets at Miner Elementary School, a predominantly Black public school in Washington, DC’s H Street Corridor.

While walking through the streets, passing brightly colored brick buildings, each with its own stoop and porch, Justin has grown comfortable retelling the story he has heard about the neighborhood. The H Street Corridor was devastated by the 1968 riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. “Just a few years ago, you could still see the burn marks on the buildings,” he says. “But they’re being painted over now.” H Street, which is now known for its trendy restaurants and designer shops, has been on the front end of rapid change and gentrification in Northeast DC.

Justin was part of the team that planted Christ City Church, originally a parish of The District Church, in this neighborhood in 2013. Learning to be a good neighbor in a community threatened by change and displacement is an essential concern for Justin as a pastor, whose congregation is made up of both native Washingtonians and transplants. “It’s one of the ways we’re wrestling now,” he says. “We’re predominantly transplants, we’re predominantly middle class with resources to move and all that.” The question is, he says, “How do we become a multiclass church? How do we wrestle with gentrification and our place in that?”

While they’re trying to understand their place in the neighborhood, Justin’s church is also debating its own theological identity, navigating LGBTQ conversations. “We got tired of seeing queer folk walking away because they didn’t feel like they could stay,” he says. “But we’re also a community that is theologically diverse. We’re trying to pursue unity in Christ, not uniformity, while also centering the marginalized—in this case that is folks who identify as queer.” Christ City Church, like many churches, is full of competing identities and visions. It is forming its identity as a transplant in a new space.

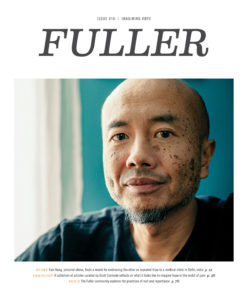

When you ask Justin about how to pastor a church that is trying to understand itself and its place in a foreign land, he starts with himself and his experiences of migration, having been born and raised in Hong Kong. Living in LA and DC—a city that embodies a Black-White binary with large Black and White populations but very few Asians and Asian Americans—propelled him to ask new questions about the world he entered and about himself in that space. “Starting at Fuller was my first time living in the US. I remember arriving here, hearing the stories of friends of color—about this thing called race. It was a whole new world that I had to figure out and research,” he says. Figuring out the undercurrents of a culture have become second nature to him. “After moving around a bunch, my inclination is always to listen first. Learn the history, the lay of the land, and what’s going on underneath the surface.”

For Justin, there is another layer of complexity when it comes to his experiences “transplanting” in the US. “I have to navigate my own identity as Asian American and learn the history of Asians in America,” he says. “We are people of color, but we don’t fit in the Black-White binary. We have experienced indentured servitude, we’ve been exploited, we’ve been otherized.”

“Every Asian American has had the question asked of them, ‘But where are you really from?’ And for me, yeah, I was born in Hong Kong, I can answer that question in a way that they’re expecting me to,” says Justin. “But it still adds to a lack of settledness. Not just do I belong here, but where do I belong, period?”

Justin remembers a conversation he had more than a year ago with Kathy Khang, a Korean American author. “How do I navigate this?” he asked her. “I don’t feel like I fit in the box. I was born an American citizen, but I didn’t live here until I was 23. My parents moved back to Hong Kong from the US. I don’t know what box I fit into.” Kathy told him, “The journey is part of the process—learning to share where you’re at right now, not expecting yourself to have it all together.” Justin reflected on that advice. “It’s hard to acknowledge that I might not have it together,” he admits. “Because then you’re like, should I even share? Should I even share where I’m at? But at the same time, we’re always functioning from imperfection and incompleteness.”

“So I’m always figuring out ‘who am I and what’s my space?’” he says. “What’s the place for my voice and what’s the place that I have to listen? What’s the place I have to step up and engage? All of that has shaped and formed who I am as a pastor now.”

Justin guides his church through those same questions that come from his own story. As a transnational Asian American with experience processing his identity in LA and, for the past 10 years, in Washington, DC, Justin hopes to lead his church of transplants and locals in learning who they are together in the Black and gentrifying H Street Corridor—when should the church raise its voice, when should it listen, and how should it engage? Justin leads his church to listen honestly to itself and to the neighborhood. This is reflected in the collaborative nature of Christ City Church, as Justin considers himself part of a team there—pastors, elders, staff, leaders, and congregants, all committed to living out the gospel in their city. “We don’t have an attitude of showing up with solutions. We’re asking folks how we can help.”

Schools are often a hub of neighborhood life, and as H Street experiences the intense shifts of gentrification, Christ City Church has found its place by supporting a local public school and its families. The church has been meeting at Miner Elementary for six years, and by now, Justin says, “The administration and the Parent-Teacher Organization know that if they ask for something, we show up.” One example is providing childcare for PTO meetings once a month. “On the surface, you might think we’re just caring for babies,” he says. “But it’s huge. It allows for more parents to be involved in the lives of their kids.” The community itself vocalized the need for childcare, without which parents with fewer resources may not be able to be involved in the education of their children, and Justin’s church took a posture of listening and then responding to those needs.

Listening to stories is what propels Justin to take up challenging topics. “It’s not like I’m thinking, ‘What’s the next most controversial thing that we can address right now?’” No matter the topic, the impetus is conversation. For example, Justin says, “I grew up in a setting where heterosexual marriage was just presumed to be normative. But then so many folks came out to me during my first two years of ministry. I didn’t know what to do but listen.” That listening challenged his own theological constructs. “We have those constructs, concepts of black and white, this is right or wrong, until reality challenges them and then we have to wrestle with, ‘Does this fit what I thought?’”

The elders at Christ City Church mimic the same process of listening to work through their theological identity. “Our elders went through a process of reading, talking, sharing stories, and praying. Because nobody wants to draw a line in the sand that means one of our friends is walking out the door.” While listening is essential, Justin also believes that more is needed. He says, “We’re balancing the care we want to have with the conversation with pastoral urgency. This is not a theoretical conversation. There are people who are like, ‘I’m just sitting around waiting to see if you will acknowledge my humanity, and my personhood, and my relationship.’”

“I don’t want a theology that can’t handle reality,” Justin says. “I don’t believe that’s what Jesus came to do. The kingdom Jesus inaugurated engaged real-life and real-world problems. So whenever I become aware of something in the world, I chase it down and allow my theology and my understanding of how God works to be shaped by what I see—as opposed to this abstract box that you try to cram everything into to make it fit. Then the stuff that doesn’t fit you pretend doesn’t exist.” Justin, being wholeheartedly committed to the gospel that is good news for the poor and marginalized, isn’t afraid of where reality will take him or his church.

For now, every Sunday Justin and Christ City Church will gather in the cafeteria of a local school in a changing neighborhood as a congregation trying to find its way, and finding the courage to listen and to share a story that hasn’t ended yet. “You gotta figure out who you are and what God is calling you to. It would be easier for me to look at other churches and be like, ‘I wish we were where they are’ in terms of organizing and being out in the neighborhood. Maybe we’ll get there,” he says. “But you give thanks for where you are and you continue to pray for grace to keep moving to where you need to go.”