When Al Dueck was first interviewed for a faculty position in Fuller’s School of Psychology, he brought his own handmade pottery to the Geneva Room for his theological examination. “It was one of my best bowls,” he remembers. “I placed it in front of me on the table and never made mention of it.” The faculty asked him about atonement theory, his Mennonite background, and more, and when the questioning was done, he picked up the bowl and started to walk out. “But Al—what about the pot?” a professor called out from the back of the room. He responded, “That’s how I integrate theology and psychology.”

Al grins as he recounts the story in his corner office some 20 years later, books and more of his own pottery lining the walls, the windows cracking as they cool from the direct sunlight. In one framed picture near his desk, his grandson’s hands rest on Al’s while he shapes clay on a potter’s wheel. “Art has everything to do with how you bring together spirituality and psychology,” he says. “It’s integration with an artistic sensibility.” After teaching for decades at the seminary, he’s demonstrated to Fuller over and over what that sensibility might look like.

When Al was installed in 1999 as the first Evelyn and Frank Freed Professor of the Integration of Psychology and Theology, he applied an artistic sensibility to his installation. Rather than only offering a lecture, he hosted an evening of music and poetry the night before in the Pasadena Mennonite Church. An accomplished cellist and pianist performed, the Mennonite poet Jean Janzen read from her work, and donor Evelyn Freed and ethics professor Glen Stassen both presented reflections on integration. “That was very exciting; all of these people were trying to do integration from their convictions in their own contexts,” Al remembers. At the installation service the next day, he lectured on the language of psychology and theology, framed by the tower of Babel, Pentecost, and “The Language of Fire,” a poem by Janzen commissioned for the day: “Now let our tongues, like leaves, fall from their careful hold, / our fists release, trusting the tree which bore us; / Christ in our roots and crown, Spirit-wind loosening. . . .”

Word began to spread around campus about the professor who used pottery to teach about psychology and theology. In one chapel service, Al gave malleable clay to half the audience and dried clay to the other half to preach about the Incarnation and being open to the Spirit. He ended every “Introduction to Integration” course by bringing his potter’s wheel to class, giving each student a small piece of clay to mold in their hands as he worked on the wheel, offering a class-long meditation on the importance of centering, intuition, and faith. “We want certainty and therapeutic techniques that we know are sure to work, but as people made in the image of a mysterious God, there are parts of us that are mysterious,” he says. Like guiding clay into beautiful forms, “being a therapist is a creative process. It pulls on that which is not in consciousness, which is intuitive. And that demands a process of self-emptying by the therapist. It is all an incredible mystery.”

Word began to spread around campus about the professor who used pottery to teach about psychology and theology. In one chapel service, Al gave malleable clay to half the audience and dried clay to the other half to preach about the Incarnation and being open to the Spirit. He ended every “Introduction to Integration” course by bringing his potter’s wheel to class, giving each student a small piece of clay to mold in their hands as he worked on the wheel, offering a class-long meditation on the importance of centering, intuition, and faith. “We want certainty and therapeutic techniques that we know are sure to work, but as people made in the image of a mysterious God, there are parts of us that are mysterious,” he says. Like guiding clay into beautiful forms, “being a therapist is a creative process. It pulls on that which is not in consciousness, which is intuitive. And that demands a process of self-emptying by the therapist. It is all an incredible mystery.”

For Al, pottery was more than just a classroom illustration—it had become a therapeutic practice for himself decades earlier. “After several years in academia, I was living too much in my head,” he remembers. “I knew that emotionally I was missing important cues in my work as a therapist. Starting my own personal therapy was a process of softening, of moving from head to heart.” Soon after beginning his own therapy, he discovered shaping clay on a wheel as a way to reconnect his mind to his body.

Over time Al began looking not only to pottery, but to the arts in general as pedagogical tools to share with others and offer a valuable space for reflection. Now, from the classroom to the therapy office, he offers students and clients alike poetry by Wendell Berry or Mary Oliver, paintings by Marc Rothko or Chagall, and books like My Name Is Asher Lev and Madeleine L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art to help them connect their intellect to their bodies and relationships. Storytelling, he believes, is essential. “In novels, I’m always seeking out glimpses of redemption. There’s also an implicit ethic on how to live one’s life,” he says. “Novels give me a concrete and imaginative display of human nature. We need a point of commonality between faith and healing, and I believe that stories are one such point of contact.”

Al is most energized when this artistic sensibility blends with his deep commitment as a Mennonite to justice and elevating marginalized voices. More than just engaging art and culture for himself, Al has traveled around the world empowering indigenous communities who seek to rediscover the values of their own art and culture. He’s taken students to Guadalajara and Mexico City to study state violence and the paintings of Diego Rivera. He coauthored a book with Gladys Mwiti on African indigenous Christian counseling and emboldening African readers to use their proverbs and stories in their own therapeutic practices. On one trip to Nairobi, an African therapist approached Al after Gladys’s lecture and said, eyes brimming with tears, “Is Gladys really telling us that it is okay for us to use our ancient proverbs in therapy? We were always told that as Christians we needed to leave behind our past.” Al answered with an impassioned yes. “An indigenous spirituality of psychology requires us to decolonize our understanding of culture—which we often assume is like Christendom,” he says. “We have to decolonize power constantly, not give it its desired rule. I want people like that therapist to discover they have a heritage of their own.”

Al is most energized when this artistic sensibility blends with his deep commitment as a Mennonite to justice and elevating marginalized voices. More than just engaging art and culture for himself, Al has traveled around the world empowering indigenous communities who seek to rediscover the values of their own art and culture. He’s taken students to Guadalajara and Mexico City to study state violence and the paintings of Diego Rivera. He coauthored a book with Gladys Mwiti on African indigenous Christian counseling and emboldening African readers to use their proverbs and stories in their own therapeutic practices. On one trip to Nairobi, an African therapist approached Al after Gladys’s lecture and said, eyes brimming with tears, “Is Gladys really telling us that it is okay for us to use our ancient proverbs in therapy? We were always told that as Christians we needed to leave behind our past.” Al answered with an impassioned yes. “An indigenous spirituality of psychology requires us to decolonize our understanding of culture—which we often assume is like Christendom,” he says. “We have to decolonize power constantly, not give it its desired rule. I want people like that therapist to discover they have a heritage of their own.”

More recently, through a generous grant given to Fuller’s China Initiative, Al has traveled throughout China to dialogue with scholars about psychology, religion, and developing uniquely Chinese therapeutic models. “It’s not just us lecturing—it really is an exchange. We have real dialogue,” he says. “That’s always my hope.” In one case, Al took Chinese American students on a trip, and he was energized to watch as the students discovered their own cultural background. “To hear them speak in their own voice gives me incredible joy; it brings tears to my eyes every time.”

Working on a wheel, a potter cannot force how the clay takes shape. Molding the clay takes intuition and stillness. “It’s a long process of learning, but there’s an incredible moment when under your hands the clay is centered, still and turning,” Al says. “T. S. Eliot would have called this the ‘still point of the turning world.’” Without this essential step, the clay will wobble in the potter’s hands or even lose balance and collapse on the wheel. “My bowls remind me of a communion chalice; there’s a cup, and then it flares out at the top,” he reflects. “There’s a hollowing out and an openness to transcendence.” He gestures beyond the bowls and toward the sky, standing in the middle of his office with two open hands.

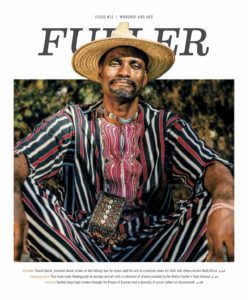

+ Al Dueck at work in his studio