Moneyball, the Bennett Miller movie adaptation of Michael Lewis’s 2003 bestseller, is that rare movie that hits a home run. An exuberant, somewhat fictionalized account of how Billy Beane transformed the Oakland A’s baseball team in 2002, this is not the typical sports movie. Unlike The Natural or Bull Durham, it is not about washed up heroes who come back one last time, or rookies that are mentored into the big leagues. Rather, Moneyball tells the story of how an impoverished baseball team switches paradigms with regard to how one should rebuild its team after its money-rich rivals buy out in the off-season the contracts of three of the A’s best players. In Lewis’s words, Beane, the A’s general manager, was willing “to rethink baseball; how it is managed, how it is played, who is best suited to play it, and why.” Beane was willing to ignore most of what he had been taught about the game and adopt new ways of projecting the team’s future. The results prove compelling on screen, as viewers root for his team to win it all.

Moneyball, the Bennett Miller movie adaptation of Michael Lewis’s 2003 bestseller, is that rare movie that hits a home run. An exuberant, somewhat fictionalized account of how Billy Beane transformed the Oakland A’s baseball team in 2002, this is not the typical sports movie. Unlike The Natural or Bull Durham, it is not about washed up heroes who come back one last time, or rookies that are mentored into the big leagues. Rather, Moneyball tells the story of how an impoverished baseball team switches paradigms with regard to how one should rebuild its team after its money-rich rivals buy out in the off-season the contracts of three of the A’s best players. In Lewis’s words, Beane, the A’s general manager, was willing “to rethink baseball; how it is managed, how it is played, who is best suited to play it, and why.” Beane was willing to ignore most of what he had been taught about the game and adopt new ways of projecting the team’s future. The results prove compelling on screen, as viewers root for his team to win it all.

As the movie opens, Beane realizes that the small budget made available to him by the club’s owner would never allow him to win against those teams like the Yankees with four times his resources if he continued to use the same strategies they used. If that was how he played the game, “moneyball” would always trump his “baseball.” Beane concluded that his seasoned scouts who had been prognosticating player-success the same way for thirty years, picking who they subjectively believed to be the best good-looking prospects who fielded well and had high batting averages, could no longer dictate his actions. After all, they once had picked him, causing him to forsake a college education at Stanford, and he had proven a bust. A new paradigm on which to build for the future was called for. Beane, therefore, chooses to take the wisdom of a young, pudgy geek, a recent graduate of Yale in economics by the name of Peter Brand.

Brand was committed to a kind of quantitative analysis known as “sabermetrics” to track those undervalued players who had a high on-base percentage, even if their batting average was lower. He was convinced that the game was won by having a higher number of runs scored, and those who got on base by any and all means, however unglamorous, were those best able to help a team when the big hit arrived. Using Brand’s wisdom and computer results, Beane trades for a team of no-names over the strong objection of his manager and scouts. (When Art Howe uses his power as manager, for example, to play another first baseman, Beane simply uses his power as general manager and trades the player.) And, after some initial growing pains, the team gels into a pennant contender. Viewers find themselves rooting for Beane and his new system to succeed, despite Beane’s continuing personal rough edges. As one reviewer wrote, “Moneyball is a story about how Billy, with Peter’s help and his laptop crammed with numbers, trades old knowledge for new.” Or as Beane tells his team, “Adapt or die.”

Brand was committed to a kind of quantitative analysis known as “sabermetrics” to track those undervalued players who had a high on-base percentage, even if their batting average was lower. He was convinced that the game was won by having a higher number of runs scored, and those who got on base by any and all means, however unglamorous, were those best able to help a team when the big hit arrived. Using Brand’s wisdom and computer results, Beane trades for a team of no-names over the strong objection of his manager and scouts. (When Art Howe uses his power as manager, for example, to play another first baseman, Beane simply uses his power as general manager and trades the player.) And, after some initial growing pains, the team gels into a pennant contender. Viewers find themselves rooting for Beane and his new system to succeed, despite Beane’s continuing personal rough edges. As one reviewer wrote, “Moneyball is a story about how Billy, with Peter’s help and his laptop crammed with numbers, trades old knowledge for new.” Or as Beane tells his team, “Adapt or die.”

Of course for the movie to work there needs to be a smart script, talented actors, and an accomplished director. Moneyball has all three. Bennett Miller, whose earlier movie, Capote, was nominated for an Oscar, took over a troubled production and guided the story with a sure hand. Steven Ziallian (who wrote Gangs of New York and Schindler’s List) and Aaron Sorkin (whose script for The Social Network was about the creation of Facebook, but also much more) worked on the script. Together, these writers produced a compelling storyline with clever dialogue. As importantly, they wrote a movie that transcends baseball.

Of course for the movie to work there needs to be a smart script, talented actors, and an accomplished director. Moneyball has all three. Bennett Miller, whose earlier movie, Capote, was nominated for an Oscar, took over a troubled production and guided the story with a sure hand. Steven Ziallian (who wrote Gangs of New York and Schindler’s List) and Aaron Sorkin (whose script for The Social Network was about the creation of Facebook, but also much more) worked on the script. Together, these writers produced a compelling storyline with clever dialogue. As importantly, they wrote a movie that transcends baseball.

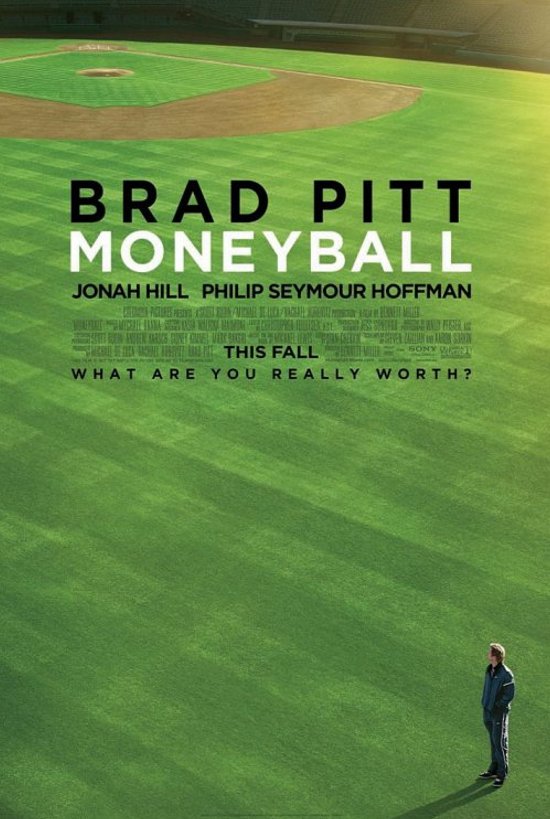

Key to the movie’s success is also the chemistry between Jonah Hill as Peter and Brad Pitt as Billy. Brad Pitt is at his best; he should get an Oscar nomination. Willing to play down his rugged, good looks, Pitt is at one and the same time inviting and unsettling, confident and yet filled with self-doubt. Viewers never move far from the sense that Beane must prove himself not only to others, but to himself. Moreover, Pitt allows his character’s acerbic and a-social character traits to remain in play throughout the story, even as his role as the “good guy” emerges. The movie never becomes saccharine. And Jonah Hill, more used to being showcased in Judd Apatow comedies that are rude and crude, but also humane and with a moral, almost steals the movies from Pitt. He too is an Oscar contender. Hill’s deadpan humor and pinpoint timing play off Pitt’s character brilliantly. His somewhat more serious roll as the pudgy genius provides Beane both his new game-plan and a confidant who is endearing.

The subtitle of Lewis’ 2003 best-seller was “The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.” This sums up exactly the appeal of Moneyball. Why we are attracted to this movie goes beyond its entertainment value or the potentially award-winning performances of its two lead characters. Beyond the humor, smart script, and personal chemistry, is our recognition that many of life’s games are also unfair. We also sense that today, we must “adapt or die.” We will no longer succeed playing with old game plans.

The subtitle of Lewis’ 2003 best-seller was “The Art of Winning an Unfair Game.” This sums up exactly the appeal of Moneyball. Why we are attracted to this movie goes beyond its entertainment value or the potentially award-winning performances of its two lead characters. Beyond the humor, smart script, and personal chemistry, is our recognition that many of life’s games are also unfair. We also sense that today, we must “adapt or die.” We will no longer succeed playing with old game plans.

This is the reason that executives throughout the entertainment industry both discussed the book when it came out and quickly bought its option. In just about every seminary across the country, there is the similar recognition that unless we adopt new measures and new metrics, unless we change the way we go about projecting our endeavors, we will no longer be effective in serving the church. We might not even long be in business. The same sense of a changing scenario holds true for those running hospitals. Even the very best stand-alone hospital knows that within ten years, it will be out of business if it doesn’t reinvent its business model. Does the same go for the church? I think it does.

To give but one example, my church is soon to celebrate its one hundredth birthday. It sits in the shadow of a mega-church with ten times our membership, multiple times our budget, and every specialized ministry conceivable. Can we as a church of 250 members compete with them? Not if we adopt their paradigm. Not if we try to use the same criteria for selecting staff, try to develop the same programming (only dumbed down to our budget), try to have the same quality of professional excellence, and so on. Instead, a new set of metrics is called for; one based on a new vision of what our church can and should be.

To give but one example, my church is soon to celebrate its one hundredth birthday. It sits in the shadow of a mega-church with ten times our membership, multiple times our budget, and every specialized ministry conceivable. Can we as a church of 250 members compete with them? Not if we adopt their paradigm. Not if we try to use the same criteria for selecting staff, try to develop the same programming (only dumbed down to our budget), try to have the same quality of professional excellence, and so on. Instead, a new set of metrics is called for; one based on a new vision of what our church can and should be.

Our less resourced church needs a minister, for example, who will be my pastor and not just my preacher; he/she needs to know the names of my children. We need a worship service that promotes community by building into it lay participation and congregational prayer, turning our size into an asset. We need a few well-focused outreach ministries (in our case, we house Pasadena’s only shelter for the homeless on cold nights) that both make a difference and allow for congregational participation.

If smaller churches simply aspire to become smaller versions of bigger churches, they will dwindle. If, instead, they opt for a strategy tailored to who they are, they might not only succeed in their mission, they might thrive. Moneyball invites its viewers to find in it a parable – a story about the art of winning given unfair odds. Here is a movie to show to your church’s leadership, and then to have a discussion about how its wisdom might fit your own “unfair games.”