The first task of a prophet is to make the invisible visible. Prophets usually do so through symbolic acts, or what some biblical scholars call “prophetic drama.” For example, God commanded the prophet Isaiah to walk naked for three years “as a sign and portent” of coming judgment (Isa 20). God commanded the prophet Hosea, “Go, marry a prostitute and have children of prostitution, for the people of the land commit great prostitution by deserting the Lord” (Hos 1:2). God commanded the prophet Jeremiah to wear a wooden yoke, like the ones farmers used to control oxen, as he walked through the streets of Jerusalem to show the people that God wanted them to “bow the neck to the king of Babylon” (Jer 27). These are but a few examples of God’s prophets using symbolic actions to reveal to God’s people what they would otherwise not see. To my surprise, God called me to do a similar thing.

The first task of a prophet is to make the invisible visible. Prophets usually do so through symbolic acts, or what some biblical scholars call “prophetic drama.” For example, God commanded the prophet Isaiah to walk naked for three years “as a sign and portent” of coming judgment (Isa 20). God commanded the prophet Hosea, “Go, marry a prostitute and have children of prostitution, for the people of the land commit great prostitution by deserting the Lord” (Hos 1:2). God commanded the prophet Jeremiah to wear a wooden yoke, like the ones farmers used to control oxen, as he walked through the streets of Jerusalem to show the people that God wanted them to “bow the neck to the king of Babylon” (Jer 27). These are but a few examples of God’s prophets using symbolic actions to reveal to God’s people what they would otherwise not see. To my surprise, God called me to do a similar thing.

In the summer of 2016, a young man named Philando Castile was shot by a local police officer in front of his girlfriend and their four-year-old daughter. This tragic, lethal encounter with police was seen by many as a clear instance of racial profiling. Consequently, it became a national headline, sparking widespread protests against police brutality and reinvigorating the Black Lives Matter movement.

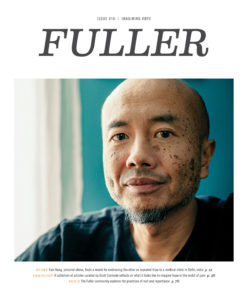

Three weeks after Castile’s death, I had a vision: I was walking past a park in downtown Pasadena, California. From inside the park I could hear a street preacher. My curiosity led me to follow the man’s voice, and when I came to where the messenger was standing, I saw that the street preacher was me. I was standing next to a large, white granite boulder. On the stone was written all types of racial injustices. I was reciting whole passages from Isaiah and Revelation, announcing a world full of justice and free of racism.

When I came back to myself, alone in my living room again, I began to weep. I was crying because I felt like the vision was an instruction and I did not want to do it. It was a call to engage in prophetic drama.

The next day, I did what the vision commanded; I began pulling the largest boulder I could manage atop a rolling flatbed wagon. On the boulder, I had written the racial injustices that weigh heavily on many Black people every day: police brutality, white fragility, mass incarceration, the names of victims of state violence, and microaggressions, to name just a few.

For the next four months, I dragged that boulder everywhere with me. I took it on job interviews, to class, to work, to dinner with friends. I almost took it on a date, but she ended up just coming to my house for dinner. Some people were proud of me for doing what I felt compelled to do. Some people were upset with me for “stirring up trouble.” I was ambivalent—feeling silly for making a spectacle of myself, but compelled to keep going, and relieved to finally be living honestly. I’d only known the world to be hostile to those who speak up about racial injustice. So, for a long time, my mouth had been sewn shut about such injustice. Carrying the boulder was a way of telling the whole truth with my whole body. It felt good to be honest.

I got a lot of questions about my actions. I eventually learned to tell inquirers that the boulder represents the burden that systemic racism lays on the psyches of many Black Americans. I wanted to make visible the burden that I carry each day, a burden that many people neither see nor acknowledge.

I eventually posted about the boulder on Facebook, to save myself the energy of repeatedly explaining what I was doing and why. One commenter asked, “What good will it do?” It was a good question. What type of success can one expect by doing things like walking about naked for a few years, marrying a shrine prostitute, wearing an ox yoke, dramatizing a foreign invasion, or lugging a stone around their city to speak truth to power? Can symbolic actions confront social injustice in any meaningful way?

The short answer is yes. But to understand how, one must understand a few things about the anatomy of the struggle for progress.

Winning the Symbolic Contest

The first thing one must understand is that half the battle for social progress has to do with our common sense. By common sense, I mean the dominant frames that inform the way we think about ourselves and live in the world. The other half of the battle is the institutional structure of our society through which we express our common sense. For example, race apartheid is an institutional expression of a white supremacist common sense.1 Jonathan Smucker, a scholar-activist and prominent leader of the Occupy Wall Street movement, refers to the battle over a society’s common sense as the “symbolic contest.”2

Symbolic actions don’t have a direct effect on the structure of society. Just as the prophets didn’t stop the exile with any of their prophetic drama, I didn’t convince the Pasadena Police Department to change their policies because I carted a stone around town. Symbolic actions, however, are well-suited for dealing with the cognitive obstacles to social progress.

Cognitions in general are a source of political power that can be cultivated to support the status quo—or wielded against it. Fear, apathy, and despair are three obvious cognitions that serve to keep people from mobilizing for progress. The task of the activist is to strategically confront those kinds of barriers by inducing what sociologist Doug McAdam calls “cognitive liberation.”3 Cognitive liberation is the process by which people come to see their situation as both unjust and changeable. It is also the path to winning the symbolic contest.

The appropriate methods for this half of the struggle are different from those that effect change on the structural level. Laws can be passed to produce greater social equity, but policy can’t erase the fear of the other. Policy alone can’t transform the myths that distort our society’s imagination with xenophobic visions. The way to convert fear to courage, apathy to love, and despair to hope is through the imagination. And we access the imagination through story, art, and symbol. Two of the most formidable cognitive blocks to progress that must be overcome through the imagination are apathy and cynicism.

Confronting Apathy with Lament

Activists often find themselves crying, “Where is your outrage?!” at an apparently apathetic society, just as the Old Testament prophets lamented they were preaching to a nation that “doesn’t know how to blush at her sins” (Jer 6:15). The fact that making the invisible visible is an activist’s essential task tells us that many social injustices are difficult to see, especially by those who do not suffer under the weight of them. Social distance and ideology obscure the systemic violence that marginalized people experience every day.4

Some of the big lies in American society that obscure racial problems, for example, are the notions that the Emancipation Proclamation ended racism, that America is the world’s most exceptional democracy, and that racism is largely about personal feelings of emotional hate. These misconceptions are often used to justify inaction on racial issues. In response, a prophet might say that we live in a culture that is reluctant to grieve its racial sins.

Grief, however, is an essential movement toward social progress because we can only change the social problems that we are willing to confess. In making the invisible visible, activists share in the essential prophetic task to engage the community with what theologian Walter Brueggemann calls the “language of grief,” that is, “the rhetoric that engages the community in mourning for a funeral they do not want to admit.”5

The biblical name for the language of grief is lament. Lament is unfortunately an underused form of prayer in the North American church that allows the petitioner to name the vicissitudes of life, including social oppression, in the presence of God (see Psalm 137). The Scripture identifies this mode of prayer as the spark that initiates salvation history: YHWH is summoned by the cry of the oppressed Israelites to deliver them from Egyptian bondage (Exod 3:9).

Lament confronts the cultural narratives that obscure social injustice. Lament challenges the ecosystems of apathy and numbness that support oppressive societal arrangements, creating space for people to engage the social injustices that were previously invisible. But American culture is averse to lamentation.

Many Americans seem to be convinced that talking about racism can only exacerbate racial divisions, that talking about our country’s racist history keeps us living in the past. My experience has been the opposite. Carrying the boulder was an ongoing lament that drew me into deeper community with other racial justice sympathizers and invited them to take action alongside me.

My friend Aaron provided the boulder that I carried around Los Angeles. He had a number of them lodged in his yard. When I came to pick it up, he asked, “When is your Sabbath?”

“Saturday,” I replied.

“Then I’ll come and pick this up from you every Saturday and bring it back to you on Sunday,” he said. He kept his word.

Years later, I posted to Twitter, saying, “White people, tell me of a time when a black person confronted you about racism and you stepped back, considered what they had to say, and made lifestyle changes.” Aaron replied to my post: “You did that for me, Andre.” That is what community shaped by lament should be.

On one occasion, I had arrived at the steps of my home church. I stopped and looked at that staircase for a moment and let out an exhausted sigh, as I realized there was no way I was going to get that wagon up those steps. To my surprise, four other men surrounded the wagon, lifted the boulder up and walked it up the stairs, without my having to ask! Symbolically, this episode demonstrates what can happen when we allow ourselves to lament. Other people can come alongside us—and join the movement toward a remedy—if we’re willing to state the problem, to point it out to them.

There was even one week when local San Gabriel residents signed up for times to come to my house, pick up the boulder, and take it with them to give me a break. Many of those people I had only known through the internet.

A few months later, my neighbor J. R. Thomas, a mentally ill father of eight, was killed by the Pasadena police while having an episode. This was the exact kind of injustice I had been protesting, so I knew that I had to respond. I decided that a memorial should be built for J. R. at the doors of the Pasadena Police Station. And for the year that followed, a group of concerned citizens met at the doors of that police station to hold a vigil in protest of J. R.’s death. Aaron helped organize it, one of the guys that carried the boulder up the church steps was there, and several of my internet friends who carried the boulder to their workplaces and dates became the core team to keep the vigil going.

All of these stories remind me that people are not always inactive due to apathy. Sometimes people care deeply but don’t have the first clue about what they should do. Sometimes people don’t care because they can’t see the injustice. And in those cases where there really is apathy, lament can be a powerful method to induce the type of grief that leads to action.

Confronting Cynicism with Hope

Movements for social change only happen when people believe that change is possible or that their efforts will be worthwhile. If people believe their votes are useless, extinction is inevitable, or that the authorities will always succeed in squashing a movement’s activity, they are much less likely to mobilize. Only hope can counteract our collective drift toward cynicism.

It is a mistake to limit the task of prophetic drama to expressing grief and pronouncing judgment. Writes Brueggemann, “Alongside this intense preoccupation with the burden and demand of the present, the prophets characteristically anticipate Yahweh’s future; that is, they think eschatologically, and mediate to Israel an imagined possibility willed by Yahweh.”6

Hope is about alternativity. At the end of the day, part of what keeps people from pursuing positive social change is the inability to imagine alternatives. Political scientist Gene Sharp puts forth that idea in his essay Making the Abolition of War a Realistic Goal. Some creative alternative must be offered to counter the idea that war is inevitable, he argues.7 And he takes his own advice by providing a blueprint throughout the rest of the essay, based on years of research, to explain how unarmed, ordinary civilians could ward off a foreign invasion through nonviolent struggle. It sounds unimaginable! But his ability to envision an alternative to violence has made his work widely used in successfully toppling dictators around the world. We need more prophetic imagination, to envision the unimaginable and break down our mental walls of despair and liberate us to hope.

To confront cynicism, we need to have humility about the future. Months into my protest, a college friend named Paul sent me Rebecca Solnit’s book entitled Hope in the Dark. Paul could see that so much time in constant public grief was beginning to consume me alive. Solnit’s writing began to poke holes in my ideas about the nature of hope. “Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists,” she writes. “Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists take the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting.”8 Before reading those words, I felt pressure to hold a kind of certainty about the future. At that time, my idea of being hopeful meant that I could answer that Facebook commenter, the one who asked me what good could dragging a boulder do, with a confident “This will do plenty of good!” Solnit convinced me that “maybe” is actually the language of hope. The truth is that I have no idea if America will become a truly antiracist society. Oftentimes, the injustices we witness, and the systems that make them possible, make certainty about social progress untenable and untrustworthy. But I am confident that it is possible, and that every citizen can play a part in building such a society. It is not inevitable but it is possible, and possibility is what hope is all about.

The prophets tell us about the world God desires to bring about, a world free from all of the fatal phobias and isms of history, a world where tears are obsolete. However, those visions don’t give us license to wait passively for God to bring that future into fruition. Instead, those visions of a coming age, where God makes all things right, serve as the grounds for summons to live in the world as God always intended in the present. The message is not, “Relax. Everything will be fine,” but rather, “Repent. The reign of God is at hand.”

We have everything to gain from answering the call to grieve the social injustices our society is trying to ignore. The guy walking around with an ox yoke on his shoulders or lugging a boulder around town is trying to reveal more to us than social pain—each is trying to make the road leading to true hope visible for those who can’t yet see it.

Endnotes