Bridesmaids, the highest rated R-rated female-starring comedy of all time, releases for home viewing this Tuesday. Janna Gould explains why we shouldn’t have been so surprised it is so funny.

_______________________________________________________________________

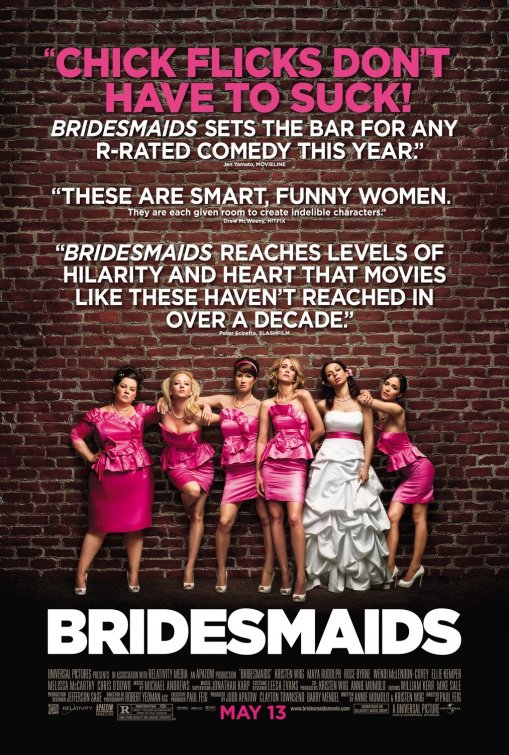

“Chick flicks don’t have to suck!” boasts the movie poster for the 2011 film Bridemaids. The film was written Annie Mumolo and actress Kristen Wiig, which means the movie has behind it the force of over twenty years of comedy writing and acting. The caliber of the movie’s humor should not have been surprising; it should have been expected. Yet somehow the hype about the film seemed to be condensed to shock about its surprising, actual hilarity. Its actual hilarity is surprising, of course, for two reasons: the film’s genre and the writers’ gender.

“Chick flicks don’t have to suck!” boasts the movie poster for the 2011 film Bridemaids. The film was written Annie Mumolo and actress Kristen Wiig, which means the movie has behind it the force of over twenty years of comedy writing and acting. The caliber of the movie’s humor should not have been surprising; it should have been expected. Yet somehow the hype about the film seemed to be condensed to shock about its surprising, actual hilarity. Its actual hilarity is surprising, of course, for two reasons: the film’s genre and the writers’ gender.

Bridesmaids is a chick flick, a film genre aimed at a primarily female audience that boasts certain sentiments and contains certain narrative elements: a(n unrealistic) love story, strong friendships, enviable fashion. Chick flicks are not typically entertaining to men partly because of these elements but also because they (apparently) often lack one major component: humor.

The second basis for surprise at the film’s success is the gender of the writers. One reviewer, Drew McWeny, remarks that Mumolo and Wiig are “smart, funny women.” While it would be nice to read such a review as a simple, to the point use of adjectives, the fact that McWeny makes this point at all perhaps reveals the true sentiment behind his statement: “These women are actually smart and funny.” That is, women are neither typically smart nor funny. And therefore, it’s surprising that a film written by women is funny. (Think about it. When is the last time a movie was advertised as by “smart, funny men”? Smart and funny are characteristics thought to be innate to men.)

I found the film both genuinely entertaining and perplexing. I laughed (at times uncontrollably and louder than my theatre-mates). I was entertained by the over-the-top-ness of the characters and was endeared by the relatability of Annie, Kristen Wiig’s character. But I was also puzzled. While some of the humor was good, situational comic gold (much of it based on the experience of being female in the West), much of it was, well, very masculine. Bridesmaid Megan (played by Melissa McCarthy) provided much of the comic relief. But her character is a masculine woman, a no-nonsense, top-secret government worker. “Ladylike” is not in her personal vocabulary (although her fake nails and pearls throughout the film are confusing). She makes fart jokes and inappropriate, lowbrow sexual references. And yet it is her character that all the men in the audience seemed to find funny.

I found the film both genuinely entertaining and perplexing. I laughed (at times uncontrollably and louder than my theatre-mates). I was entertained by the over-the-top-ness of the characters and was endeared by the relatability of Annie, Kristen Wiig’s character. But I was also puzzled. While some of the humor was good, situational comic gold (much of it based on the experience of being female in the West), much of it was, well, very masculine. Bridesmaid Megan (played by Melissa McCarthy) provided much of the comic relief. But her character is a masculine woman, a no-nonsense, top-secret government worker. “Ladylike” is not in her personal vocabulary (although her fake nails and pearls throughout the film are confusing). She makes fart jokes and inappropriate, lowbrow sexual references. And yet it is her character that all the men in the audience seemed to find funny.

Further, one particular scene on an airplane seems written solely to entertain (heterosexual) men. Badass mom and bridesmaid, Rita (Wendi McClendon-Covey), and the young, innocent bridesmaid, Becca (Ellie Kemper), get drunk on airplane cocktails and make-out with each other. At the risk of sounding like my mother I must say that this bit adds nothing to the scene or the overall story. It seems the only function this scene serves is to provide shock value and the elicitation of a laugh. And one must ask, a shock of value to whom? Elicitation of a laugh from whom? Probably heterosexual men.

Further, one particular scene on an airplane seems written solely to entertain (heterosexual) men. Badass mom and bridesmaid, Rita (Wendi McClendon-Covey), and the young, innocent bridesmaid, Becca (Ellie Kemper), get drunk on airplane cocktails and make-out with each other. At the risk of sounding like my mother I must say that this bit adds nothing to the scene or the overall story. It seems the only function this scene serves is to provide shock value and the elicitation of a laugh. And one must ask, a shock of value to whom? Elicitation of a laugh from whom? Probably heterosexual men.

Now, I will be the first to argue that there is nothing inherently male about these kinds of qualities (lowbrow sexual reference, fart jokes, being entertained by women-on-women action). But a point does need to be made about what society and popular culture have deemed masculine, and therefore, funny. In this sense, it’s not just women that should be offended by the sexism involved in the marketing and popularity of Bridesmaids. But men too should be offended that the elements added to the story to attract a male audience are sophomoric and distasteful, at best.

Now, I will be the first to argue that there is nothing inherently male about these kinds of qualities (lowbrow sexual reference, fart jokes, being entertained by women-on-women action). But a point does need to be made about what society and popular culture have deemed masculine, and therefore, funny. In this sense, it’s not just women that should be offended by the sexism involved in the marketing and popularity of Bridesmaids. But men too should be offended that the elements added to the story to attract a male audience are sophomoric and distasteful, at best.

If butch bridesmaid Megan were not in the bridal party would Bridesmaids have succeeded in the eyes of men (and, therefore, the public) as it did? Something tells me it wouldn’t have, which is a shame because Kristen Wiig is hilarious, as a writer and an actress. She is an obvious student of human nature and the female experience, able to translate both into comedy.

The denial of or felt surprise at the female ability to be hilarious is probably one of the most persistent and prevalent forms of sexism in pop culture today. Esquire magazine recently published a list of women they find funny. There were twelve women on the list. And while Esquire notes with an asterisk that the list is not exhaustive, the very existence of a list insinuates the rarity of funny women. The myth that women aren’t funny (and its sister-myth that in order for women to become funny they must become more “masculine”) needs to be destroyed. Women are funny. While I am tempted to prove it to you by providing for you an Esquire-esque list of my own containing the names of women I find funny, I will refrain, as the ability of women to be funny shouldn’t have to be proven. Proving the existence of funny women is as useless as proving that trees exist. You don’t have to prove it. They’re everywhere. Just look around. And, “funny” men, you might have to shut up in order to actually hear them.

The denial of or felt surprise at the female ability to be hilarious is probably one of the most persistent and prevalent forms of sexism in pop culture today. Esquire magazine recently published a list of women they find funny. There were twelve women on the list. And while Esquire notes with an asterisk that the list is not exhaustive, the very existence of a list insinuates the rarity of funny women. The myth that women aren’t funny (and its sister-myth that in order for women to become funny they must become more “masculine”) needs to be destroyed. Women are funny. While I am tempted to prove it to you by providing for you an Esquire-esque list of my own containing the names of women I find funny, I will refrain, as the ability of women to be funny shouldn’t have to be proven. Proving the existence of funny women is as useless as proving that trees exist. You don’t have to prove it. They’re everywhere. Just look around. And, “funny” men, you might have to shut up in order to actually hear them.

________________________________________________________________________

Janna Gould is a second year MAT student. You can read her personal blog at jannagould.com (it’s not that funny).