At the Oscars, so much attention is paid to the Best Picture nominees. That’s fine, I suppose, since most of us exclusively watch feature length, fictional narrative films. In years like 2013, there are lots of great narrative features to watch. And of course, Hollywood is an industry, and the movies nominated in the Best Picture category are the top products of the movie-making industry, their finest money-makers (though, thankfully, making money isn’t the most important determiner of a movie’s Oscar hopes).

As the distribution channels continue to flatten, we increasingly have the opportunity to view some of Oscar’s other gems. All five of the nominees for Best Documentary Feature are available to stream online, four of them from the same streaming video service (Netflix). They’re each worth your time.

Concerning the Oscars, there is one documentary I think should win – The Act of Killing – for being one of the most exceptional and unique documentaries I’ve ever seen. There is one I wish would win – Cutie and the Boxer – because it affected me most deeply, as I share its love and concern for artists. There is also one I expect will win – 20 Feet From Stardom – because I imagine it will have the most resonance with Oscar voters. Honestly, I’m impressed by all five of these documentaries, and in at least this one category this Sunday, I’ll be pleased with the results regardless (and especially if a little golden statue encourages a few more people to watch any one of these films).

Below are capsule reviews of each of the five nominated films.

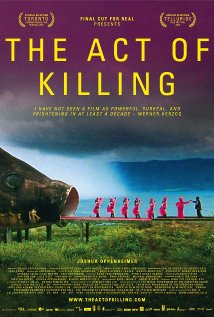

The Act of Killing

The Act of Killing

I reviewed The Act of Killing in depth back in August. This isn’t always the case, but I stand by my review. Here’s an excerpt:

The shock of The Act of Killing is in the graphic openness with which these men discuss the ways they killed, raped, and extorted (and still extort) the weaker members of Indonesian society. The Act of Killing is primarily explicit anecdotally – the men talk about what they did. This lessens the affect of the acts somewhat, but the film’s focus on telling also makes their pride all the more striking. The telling is the point. This film attempts to expose the ways we glorify societally in mass murder “for the common good.”

We are not supposed to despise Anwar Congo and the other gangsters interviewed in the film. We are supposed to identify with them, to see ourselves in them, to reflect on all the ways we too glory in genocide. We arenot meant to hate them. We are meant to empathize with them. As Oppenheimer states, “In The Act of Killing, I ask you to see a part of yourself in Anwar, a man who has killed perhaps 1,000 people… The moment you identify, however fleetingly, with Anwar, you will feel, viscerally, that the world is not divided into good guys and bad guys—and, more troublingly, that we are all much closer to perpetrators than we like to believe.”

20 Feet From Stardom

20 Feet From Stardom

20 Feet From Stardom features interviews with and the histories of some of the music industry’s most celebrated and overlooked back-up singers. The film is mostly heads-up interviews and archival footage of concerts interspersed sporadically with snippets of live performances done expressly for the documentary. The film bills itself as a crowd-pleaser, and it is certainly that, full of music you know and a lot of applause for people (almost all of them women) perpetually on the edge of the spotlight.

The film is very concerned with why these women with dynamic voices never achieved fame like the people they backed-up. Some of them sought it and were scuttled in their efforts. Others never really wanted it. They were content with standing in the shadows and singing for a living. Regardless of each performers individual desire, the film is exemplary in its eagerness to celebrate everyone, both back-up singer and star alike. The last don’t get to be first very often and this is especially true in industries founded on fame.

Dirty Wars

Dirty Wars

It seems every Oscar ballot contains at least one documentary explicitly critical of the American military. Dirty Wars is this year’s conscientious objector. The film chronicles one journalist’s obsession with uncovering the efforts of what was once one of the military’s most secret clandestine force – the Joint Special Operations Command or JSOC. JSOC is much less secret now as they were thrust into the spotlight after they successfully carried out the mission to kill Osama bin Laden. (See Zero Dark Thirty. No really, see it.)

Dirty Wars is a conscience doc, and a dour one at that. I tired of its defeatist tone, though I understand the helplessness the filmmakers likely felt as they tried to get answers out of the opaque, bureaucratic behemoth that is the United States military. Someone out there needs to make a documentary about these kinds of documentaries and question why they seem so unable to get answers to their questions.

Democracies are supposedly built on transparency between citizens and their government. The flaw in that idea, of course, is that governments are made up of people, and people are prone to deceitfulness. Documentaries like Dirty Wars cry out for the kind of revelations Jesus promises in Matthew 10 when he encourages his disciples not to be afraid of those who would do them harm,”for there is nothing concealed that will not be disclosed, or hidden that will not be made known” (Matthew 10:26). That day is coming. Come, Lord Jesus.

The Square

The Square

The number one thing that makes me cry in a movie is when one character says to another, “I forgive you.” That happens so rarely in our world. Blatant forgiveness in a story seems more magical than anything else to me. The second thing that will most often make me weep is a group of people standing in solidarity against tyranny. The Square is about just such a group of people.

The film follows a small number of people with different affiliations but the same goal – freedom from tyranny and rule by democracy in Egypt – throughout the ongoing popular protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square from 2011-2013. The film is both intimate and expansive. You get to know these few subjects well, their struggles and goals, their relationships with each other, their failures, and the you get a very good overview of the revolution itself, how it develops, falters, and where it stands as the film ends. The film is masterfully edited. Even with all the parallel stories, never once did I feel disoriented. And the film clips by like an action thriller. it’s probably the most well-made documentary of this Oscar nominated bunch.

The Square chronicles a populist uprising, so it’s natural that the film is broadly antagonistic of any allegiance other than personal allegiance to other people. Institutions of all kinds – bureaucratic, martial, national, and even religious – are depicted as needlessly complicating (at best) and tyrannical (at worst).

I want to stick up for the church here, but I’m reminded of the time the Pharisees asked Jesus when the kingdom of God would come, and Jesus answered, “The coming of the kingdom of God is not something that can be observed, nor will people say, ‘Here it is,’ or, ‘There it is,’ because the kingdom of God is in your midst.” (Luke 17:20-21) AS I watched The Square, I wished I could have been in the midst of the people in Tahrir Square. I think they’re in the right place.

Cutie and the Boxer

Cutie and the Boxer

My favorite of the nominated documentaries is Cutie and the Boxer, a cinematic photograph of a married couple, both of them visual artists, living in New York City. The premise is cute – two elderly, Japanese artists living and working together in their NYC home/studio – but the movie stops being cute as soon as the opening credits roll over a static shot of the old man wearing paint-soaked gloves maniacally slugging a wall.

Cutie and the Boxer is a movie about fighting with walls of all kinds, be they artistic, professional, or relational, and how the fighting itself can be a form of love. The movie is equal parts heartbreaking and heartwarming. It reminds me of another lauded 2013 documentary, Stories We Tell, both in subject (artists) and intention (to explore the ways we understand and process our lives via our creative pursuits). However, Cutie and the Boxer is less explicit than Stories We Tell about its conclusions and more comfortable with the inherent ambiguity in comparing people’s perspectives on their shared lives.

I love this movie, and I would make it required viewing for anyone aiming to pastor artists. Cutie and the Boxer is a unflinching look at the kinds of pain (partiularly humiliation and isolation) that most artists are made to endure for their art in our society. It takes seriously the passion of these artists. It is curious about how they can be blind to some their own limitations while being piercingly aware of some of their other limitations at the same time. This movie knows what kind of love artists need, and it knows how hard it can be to give it to them. This movie knows that the only way to love artists is to be in committed community with them no matter what. It’s also funny and warm and surprising. Cutie and the Boxer is a fantastic film.