Anyone who knows much about Baptists will quickly recognize that we do have some major challenges in articulating a suitable spirituality at this time in history. Some of these are rooted in our history, others spring from present experience. Together, they leave us with a mixed bag of both positive and negative elements. Let me enumerate some of the challenges that leap out at me as I reflect on our situation.

Individualism

One of the first is a tendency to define spirituality almost exclusively in terms of the individual. If you range religious groups across a spectrum from intentionalist/corporatist on one end (in which the Spirit is thought to effect obedience through the corporate body), to voluntarist/individualist on the other (in which the Spirit is thought to effect obedience through the individual), at the time they began, Baptists and Quakers would have occupied the extreme voluntarist/individualist end, while Roman Catholics and Anglicans would be near the extreme intentionalist/corporatist end.

Baptists shaped their spirituality largely by way of negative reaction to abuses in the exercise of authority over individuals in the late middle ages, especially the Acts of Uniformity of the Church of England. Subsequently, they imbibed heavily of the elixir of the Enlightenment. Their experience in America, where you will find almost 85 percent of Baptists, has accented individualism still more. The frontier exhibited an extreme form of individualism, but Charles Reich warned several years ago that even frontier individualism would pale alongside the extremes of “Consciousness III” which was engulfing American society.1 In their spirituality Baptists have sailed along with this tide. They have tended to place responsibility heavily on the shoulders of the individual and to eschew means for the cultivation of piety. They have looked suspiciously on formation as a threat to the liberty of the individual believer. Although you may now see a sizeable number of Baptists who seek spiritual direction and appreciate the rich heritage of Christian spirituality, they represent a small and select group within the Baptist fellowship.

Accent on Conversion

Tangential to individualism is the Baptist accent on conversion. Heavily influenced by American revivalism, Baptists in the South especially have identified salvation with the response of faith to the preaching of the Word and neglected the growth process. Emphasis on grace as God’s unmerited favor and fear of “works righteousness” have resulted often in the watering down of the divine demand to the point of irresponsibility. “Jesus paid it all, All to him I owe. Sin had left its crimson stain. He washed it white as snow,” we Baptists love to sing. The use of means to effect growth might lead to “works righteousness” and militate against a grace that leaves nothing more to be done to put ourselves right with God. Hardly anything stirred more controversy among Southern Baptists in recent years than the questioning of the popular Southern Baptist cliché, evidently invented by J. R. Graves to undergird Baptist one-upsmanship, “Once saved, always saved.”2

Like other Protestants, Baptists too have inherited from the Reformers a definition of grace too narrow to encourage a process of spiritual nurture and growth. Grace is “God’s unmerited favor,” above all, in acquitting the sinner at the judgment rather than, as Augustine expressed it, God’s gift of Godself, the Holy Spirit. Combine this with the theory of a substitutionary atonement so popular in “conservative evangelical” or fundamentalist circles which now dominate the Southern Baptist Convention, and you will find great reluctance to foster spiritual formation at all. Take the bus and leave the driving up to Jesus.

Dearth of Models and Means

Just as Baptists have shared this inadequate definition of grace with other Protestants, so too have they suffered from a dearth of models and means for the cultivation of piety negated and discarded by the Reformers. As to models, like their early forebears, Baptists have used up quite a lot of ink proving that Paul labeled all Christians “saints” and repudiating the idea of a more dedicated few. In the past and even today, they have looked with horror on the calendar of saints days, prayer through the saints and Mary, the monastic vocation, and the whole idea of “holy persons.” Well, Southern Baptists do have Lottie Moon, a missionary to China, and Annie Armstrong, a fabled “home” missionary, to appeal to in raising money for missions, but we would not want to call them saints. If the faithful emulate anyone, they should select biblical models. At the same time, Baptists influenced by dispensationalism—and they are legion in the South because of the use of the Scofield Bible—have undercut expectation of matching the level of piety exhibited there by placing the biblical era in an altogether separate category. According to dispensationalists, the Holy Spirit all but ceased to function after inspiring the last New Testament writing or perhaps held out on deathbed until the canon was closed.

BAPTIST TRADITION

The Baptist spiritual tradition has roots in seventeenth-century Puritanism, diverging from that tradition in a radical insistence on voluntary obedience. “In this central principle we can see the source of Baptist pride in idiosyncrasy from the beginning,” says Hinson, “and we may find it shocking that some Baptists would adopt highly regimented approaches that their forbears would have rejected.”

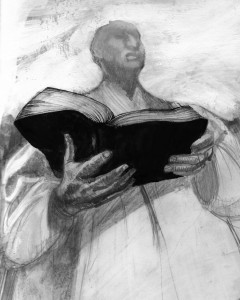

Baptists have retained two sacraments, which many scrupulously call “ordinances” to assure that they do not convey grace, but Scriptures, sermons, and prayers have taken pride of place as the means through which they expect God to communicate with the faithful. Scriptures may be the chief Baptist sacrament, that is, the means through which we receive grace. Corporate worship has revolved around reading and exposition of Scriptures. Private devotion has focused on meditation on Scriptures. And Southern Baptists are great proof texters who have engaged in a protracted controversy from the 1960s until now as to whether Scriptures are “inerrant.” Bailey Smith, then president of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), famously declared, “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” A near-bibliolatry has resulted in a circumscribing of the means through which people relate to God. Baptists have cut themselves off from the wisdom of the centuries as they have shied away from devotional classics, counting themselves “people of the Book.” Meantime, most have lost touch with the traditional approaches to Christian meditation on the Bible.

Preaching probably ranks just behind the Bible as a Baptist sacrament. Most Baptists probably would push sacraments to the background in their consideration of the magisterial Reformers’ definition of the Church as “where the Word is rightly preached and the sacraments properly administered.” The sermon is “where it’s at.” If rightly preached, it will admonish, encourage, inspire, and direct the sinful saint. It can touch every aspect of life. Using a shotgun rather than a rifle approach, however, it is questionable whether it has substituted adequately for the more personalized and individualized assistance of confessionals and spiritual directors. Baptist piety generally, as a consequence, has depended on individual, personal proclivity and effort rather than corporate design.

The same problem has afflicted the Baptist practice of prayer. Baptists talk a lot about prayer, and they include lots of space for it in their worship, but, negating as vehemently as the early Baptists did the medieval inheritance in devotion, all too many Baptists have deprived themselves of the proven methods of earlier centuries and, more costly, virtually slammed the doors shut on the main schools of prayer—the liturgy, prayer books, great prayers of Christian history, and the contemplative tradition. Some Baptists still feel very uncomfortable reciting the Lord’s prayer in public worship, and you will not attend many services in which Baptists do that. Baptists haven’t gotten over early Baptist reaction against imposed prayer forms of the Book of Common Prayer. In his treatise on prayer, composed while he was in prison in 1663, John Bunyan labeled reciting of such prayers, even the Lord’s prayer, as only “a little lip labour and bodily exercise.”3 When asked to explain how he would teach children to pray if he did not use the Lord’s prayer or other forms, he said to tell them about their wretched condition, hell fire, and damnation.4

As Baptists, along with the other Protestants, shifted from a liturgical/sacramental/confessional/contemplative to a biblical/sermonic piety, they both gained and lost. They gained something in the way of the cognitive dimension. They lost something in the way of the affective and intuitive dimensions, the cultivation of what Theodore Roszak has called “the powers of transcendence.” They have often touched the head more than the heart.5 The loss here, of course, has been offset to some extent by music, but not much even now by art and architecture. Although early Baptists fought a bitter battle over whether they could use hymns,6 their descendants have fallen in love with music and actually contributed significantly to it. Baptist hymnals probably exhibit the very best of Baptist spirituality. Baptist recovery of art, however, has proceeded more slowly and is still woeful.

Shaping Saints

The ultimate test of spirituality, however, should not rest with models and means but with effects. Have Baptists, Baptist churches, shaped saints? Have they shaped people whose lives are irradiated by grace, who seek not to be safe but to be faithful, who have learned how to get along in adversity, who are joyfilled, who are dreamfilled, who are prayerful?7 Are they shaping them today?

I have to say, though, that I think Baptists have produced too few saints and exercised too little encouragement to sanctification. Lest we feel too battered, let me hasten to add that most religious groups would suffer much the same criticism. At the same time, interest in spirituality in the past decade or so has brightened this dark picture noticeably. As a matter of fact, Jack U. Harwell recently depicted the trend in spirituality among Baptists in the South as “epidemic.”8 Among other evidences, he cited the ministry of Tom Turner as a spiritual director, his call to a vocation of prayer, the employment of professors of spirituality in Baptist seminaries, and the focus of the 1999 Cooperative Baptist Fellowship (CBF) annual meeting in Houston on spirituality. A high level of interest in spirituality is beyond question.

JOHN THE BAPTIZER

The Baptist tradition is marked by a history of nonconformism, leading to a wide diversity of beliefs joined by emphasis on baptism. Though the name has its origins with “anabaptist,” the biblical figure of John the Baptist is arguably the tradition’s earliest forebear.

El Greco, M. H. de Young Memorial Museum

From Typographic to More Iconic and Tactual Culture

The recent technological revolution brings to my mind another shift in Western culture that is impacting spirituality, perhaps both complicating and assisting Baptists as they seek to articulate a meaningful spirituality in the contemporary moment. Western culture is reversing a shift that occurred on the eve of the Reformation of the sixteenth century. With the invention of moveable type, Europeans—especially Protestants—moved from a more iconic and tactual culture to a more typographic one. Today, with the invention of television and computers, we have been shifting from a more typographic to a more iconic and tactual culture. The downside of this revolution, especially with television, is that we have become an entertainment culture.9 The upside, however, especially with computers, is that we can learn in ways not possible in the typographic era, and we can appreciate in a new way the symbols of our faith. My students, for instance, do not have the intense reservations about painting, sculpture, architecture, and other icons their forebears did. In fact, many use icons in their prayer. They also appreciate sacraments in ways their forebears could not. All of this would seem to mean that they will appropriate things from the vast treasury of Christian spirituality which the ecumenical era has put at our disposal.

A Cornucopia of Options

What the religious search of recent years has produced is a cornucopia of options in spirituality, which may help Baptists find a meaningful spirituality but also leaves them with a problem of overchoice. In his recently published book entitled Streams of Living Water: Celebrating the Great Traditions of Christian Faith,10 Richard Foster has elucidated six traditions of spirituality—contemplative, holiness, charismatic, social justice, evangelical, and incarnational. You are likely to find a little of all these specimens in spirituality somewhere among some Baptists. As a matter of fact, there is such an array that they almost defy any orderly classification. After reviewing several other ways of categorizing, Molly Marshall has settled on four types of “discipleship” or spirituality as practiced in contemporary Baptist life: conversionist, charismatic, crusading or prophetic, and contemplative.11

Sorting Options

Although the vital religious search and variety of options should be welcomed, we must recognize that they do confront us with a critical dilemma: How do we sort out these options and make sure they are going to help us attain our chief goal in spirituality—to love God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength and our neighbors as ourselves? How can we be sure they do not conflict with what belongs to the essence of our own tradition, namely, the voluntary principle in religion, that faith, to be responsible, must be free?

Our basic challenge, as I now began to see it: How do I go about the critical task of conserving the authentic insights my own tradition has bequeathed to me while laying claim also to those from the larger one? Richard Foster offers an approach to the great traditions of Christian faith, that is, that there is a certain validity in each of these and that healthy spirituality requires something of all of them. This is not to say that each is equally worthy and will give any of us all we need. Far from it. We need balance for a healthy spirituality, just as Baron Friedrich von Hügel insisted. Like the four legs under a table, a healthy spirituality requires a balance of experimental, intellectual, social, and institutional elements. Some of these traditions may not supply all those elements by themselves.

One element of our Baptist heritage will make it hard for some to bring our Baptist tradition into dialogue with the broader Christian tradition, namely, the tendency we have had to sneer at “tradition.” We haven’t learned to distinguish “tradition,” the kernel, from “convention,” the husk, and it has cost us. When the latest fad has come along, we have plunged whole hog into it. In the late fifties many joined the charismatic movement. In the sixties and early seventies many jumped on the band wagon of secular spirituality. In the later seventies and eighties some turned eastward to other religions. Now you see an obsession with “experience.” This is the age of experience seekers, and we crave experience.12 If we are to avoid shipwreck on the shoals of novelty, we had better keep the anchor of tradition handy.

ENDNOTES

1. Charles A. Reich, The Greening of America (New York: Bantam Books, 1971).

2. See Dale Moody, The Word of Truth (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981), 348–65, and the Festschrift dedicated to Dale Moody published in Perspectives in Religious Studies 14 (Macon, CA: Mercer University Press, 1987). Moody’s questioning of the Calvinist doctrine of election in the “Abstract of Principles” doctrinal statement, which the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary requires all professors to agree to teach “in accordance with and not contrary to,” led to his forced retirement from the seminary in the midst of a sharp controversy.

3. John Bunyan, I Will Pray with the Spirit, ed. Richard L. Greaves (Oxford: Clarendon, 1976), 243.

4. Ibid., 269.

5. This observation might seem to conflict with the highly emotional appeal of much Baptist preaching. However, I think emotion in fundamentalist contexts sustains certain theological convictions more than it tries to meet deep personal needs.

6. Calvinistic Baptists permitted use of the Psalms, but they feared more popular music, which might “corrupt” those who used it. Benjamin Keach, a General Baptist who transferred to the Calvinist Particular Baptists, first introduced congregational hymn-singing in his church at Horsley-down in England in 1663. He met vigorous opposition, and the introduction of hymn-singing in his church led to a bitter controversy among Particular Baptist churches. The controversy continued until 1692.

7. This definition adapts two given by Douglas V. Steere, the first in On Beginning from Within (New York: Harper Brothers, 1943), 1–32, and the second in his inaugural address as Harry Emerson Fosdick Visiting Professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York, “Spiritual Renewal in Our Time,” Union Seminary Quarterly Review 17 (November 1961), 33–56.

8. Jack U. Harwell, “Spirituality Trend ‘Epidemic’ among Baptists in the South,” Baptist Today, 2, Vol. 16 No. 4, April 23, 1998, 6–7.

9. Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (New York: Penguin, 1986), has offered this assessment of the entertainment culture’s impact on the “electronic church”: “Everything that makes religion an historic, profound and sacred human activity is stripped away; there is no ritual, no dogma, no tradition, no theology, and above all, no sense of spiritual transcendence. On these shows, the preacher is tops. God comes out as second banana.”

10. Richard J. Foster, Streams of Living Water: Celebrating the Great Traditions of Christian Faith (San Francisco: Harper/Collins, 1998). This follows the categorization of Devotional Classics, ed. Richard J. Foster and James Bryan Smith (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993), which used five categories.

11. Molly Marshall, “The Changing Face of Baptist Discipleship,” Review and Expositor 95 (Winter 1998): 67–70.

12. This seems to be what Henry Blackaby and Claude V. King are responding to in programs pushed by the Southern Baptist Convention, Experiencing God: How to Live the Full Adventure of Knowing and Doing the Will of God (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1994).

This article was published in Theology, News & Notes, Fall 2009, “Winds of the Spirit: Traditions of Christian Spirituality.”