“The senses are our bridges to the world. Human skin is porous; the world flows through you,” says John O’Donohue in his book Anam Cara. If the theology section of this issue reveals anything, it is how the expression of worship and art is embodied, and that this embodiment affects both what we absorb as the world flows through and what we release back into it. If astronomer Carl Sagan and songwriter Joni Mitchell are correct—“we are stardust, we are billion-year-old carbon”—not only the world flows in and out like breath, but an eternal cosmos, too. If the imagination can stretch that far, is it so great a leap that we, first enlivened by the breath of God in Eden, still exhale that breath back into the world? Might our service be the simple act of breathing out the presence of God in a thousand places?

This territory is not new to artists or worship leaders—or those called to intercessory prayer. I have referred before to the artist as intercessor, bridging the gap between suffering and hope (Rom 5:3–5) with one foot planted firmly in each. Why? No one in their right mind would remain in such tension by choice, yet some artists do so to become a bridge themselves, so that others might cross over them. “There is a kind of consciousness,” confirms Christian Wiman in his book My Bright Abyss, “[that] involves allowing the world to stream through you rather than you always reaching out to take hold of it. . . . People, occasionally, can be such works, creation streaming through them.” How might we be such people in a world of catastrophic change and rage fatigue? One context at a time: Lance Kagey, Artist in Residence at Fuller Northwest, is just such an artist, engaged in a unique dialogue with Seattle through the hand-printing and random hanging of original works around town. His art, found opposite this page and throughout the magazine, is thought-provoking and vital, but it is the artist himself who is in dialogue with the city, crossing the distance between thought and stranger.

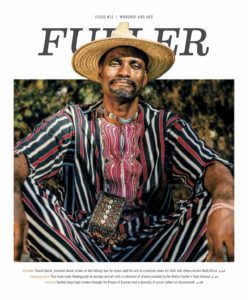

“The purpose of theology—the purpose of any thinking about God,” says Wiman, “[is] to make the . . . aspects of the divine that will not be reduced to human meanings more irreducible and more terrible, and thus ultimately more wonderful.” This is why, he goes on to claim, “art is so often better at theology than theology is.” It most certainly is true that art tells a tale of God that theology cannot (to which most theologians will attest), and vice versa. But this seminary is peopled with those who embody both theology and art at once. Daniel Dama, whose beautiful visage graces the covers of this magazine and whose story is told within, is evidence of this dual embodiment of God’s presence as theologian and musician, prompting the question, why choose between worship, theology, and art when we might embody all?

+ Lauralee Farrer is storyteller and chief creative at Fuller, editor in chief of FULLER magazine, and creative director of FULLER Studio.