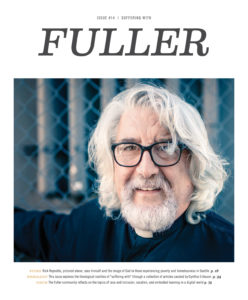

“We don’t think of ourselves as being garbage generators,” Rick Reynolds (MAT ’85) chuckles while explaining the work he stumbled into at Seattle’s Operation Nightwatch. “We got somebody hauling it off for us, whereas people sleeping outside don’t have that luxury.” His work has required him to look deeply at those who are often invisible to mainstream society, which he says has been a transformative experience.

Operation Nightwatch is a faith-based compassion ministry that seeks to reduce the impact of poverty and homelessness. Before joining the organization 25 years ago, Rick was attending Seattle Pacific University, training to become a school teacher. However, after one quarter of student teaching, he decided to drop out of the university’s School of Education. “It was my senior year; I only had two quarters to finish up, and after one quarter of teaching, I hated it,” he explains. “I have nothing but the highest respect for people who can manage a classroom. The problem was that I had a high tolerance of chaos, and that doesn’t work in a classroom.” Afterward, Rick’s vocational path led from Seattle Pacific to Fuller’s Seattle campus.

During his first quarter in seminary, Rick seemed to find his calling with Operation Nightwatch. Although he was not yet ordained, he bought a clerical collar to wear while passing out pizzas to Seattle’s poor as a volunteer with the organization. “Nightwatch said if you’re on an ordination track, which I was, they didn’t have any qualms about letting you wear the collar,” he explains. Ten years later, Rick became the organization’s executive director.

To combat homelessness, Operation Nightwatch provides some basic survival services, including a dispatch center that feeds and provides access to shelter for about 120 to 140 single adults. They also have an apartment building for 24 formerly homeless seniors. “It’s very simple housing, kind of dormitory-style,” Rick explains. “But it’s a permanent rental, so people have a bed, a dresser, a refrigerator, a place to call home, and a community around them, which is really great.” He says that these basic survival services are essential for people experiencing homelessness to get stable. Otherwise, “they tend to go from being a one-time homeless person to being periodically homeless, because they have these recurring problems, to being somebody who’s stuck on the street.”

Twenty-five years into doing this work, Rick says he has seen significant changes in the relationship between the city and its homeless population. He remembers that years ago it didn’t take long for people to move from a shelter into some kind of permanent housing. “But as the downtown and closed-in neighborhoods have become gentrified, a lot of people have been priced out,” he says. “And so that’s when despair settles in, hopelessness and then drugs and alcohol become more of an issue, and mental health issues start to surface. It’s pretty heartbreaking, really.”

Rick speaks of the divide between the city’s homeless and mainstream people as “sadly ironic.” He tells a story to illustrate that those with homes are not so different from the homeless: “The newspaper covered how an area of town was being cleared out by the authorities, and likely needed to be. The mayor was proudly showing off the mess that had been left behind by ‘filthy homeless people’ on the little greenbelt area,” he recalls. “But buried on another page was an article about a 10 million gallon sewer overflow into Lake Washington that barely ruffled anybody’s feathers at the time. Ten million gallons of sewage from people living in houses dumped into a local lake, but we’re going to focus on the half ton of garbage that homeless people left behind, because they are forced to sleep outside and don’t have anything to do with their cans and bottles and effluent.” He says he wishes people could see that “human beings are human beings, and everybody’s worthy of dignity and respect. They all have the stamp of God on them.”

The problem, Rick suggests, is that cultural lenses of prejudice often make it difficult for us to recognize the image of God in the poor. “They’re all created in the image of God, and that’s the thing: I want people to look, and not just look past.”

Working with the poor has required Rick to truly look at the poor and to confront his own prejudices.

His first year on the job with Operation Nightwatch, he had a memorable exchange with a man named Ronnie. To Rick, Ronnie fit all of the stereotypes that many assign to the homeless: “He was loud, obnoxious, drank, heard things that nobody else could hear, and was getting barred from one shelter after another.”

One night, while standing in front of the shelter with his homeless friends, Ronnie asked, “Pastor Rick, ain’t I beautiful?” Telling the story, Rick pauses for a second. “He’s looking at me with this big crooked grin on his face,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Ronnie, you’re beautiful.’ I’d come up next to him to try to do an old seminary buddy hug. And he throws his arms around me. He’s hunched down. He’s six inches taller than me. His cheek is pressed up against my cheek. Pulls back, kisses me on the cheek, and off he goes to shelter, into the night.”

One night, while standing in front of the shelter with his homeless friends, Ronnie asked, “Pastor Rick, ain’t I beautiful?” Telling the story, Rick pauses for a second. “He’s looking at me with this big crooked grin on his face,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Ronnie, you’re beautiful.’ I’d come up next to him to try to do an old seminary buddy hug. And he throws his arms around me. He’s hunched down. He’s six inches taller than me. His cheek is pressed up against my cheek. Pulls back, kisses me on the cheek, and off he goes to shelter, into the night.”

He admits that he was initially “self-congratulatory” about that exchange with Ronnie. However, upon later reflection, he had an epiphany: “Sometimes I’m the ‘Ronnie.’ I’m the one who doesn’t smell so great. I’m the one who doesn’t act right. You know? That homeless guy has got every bit of God’s grace on him that you have.”

Rick suggests that if we are intentional about looking at the poor, we’ll also have our prejudices challenged, much like his were with Ronnie. “We have these assumptions about people standing on street corners. Panhandlers are who we see,” he says. “But if you just keep your eyes open, you’re going to see homeless people that go to work every day, and homeless people that are doing the best job they can to stay out of trouble, and are peaceable, funny, intelligent, talented people.”

Sometimes Rick has run into a homeless person he knows through Operation Nightwatch at their workplace. “They’re horrified that I’m going to out them, because there’s such a stigma attached to being homeless that nobody wants to let anybody know, and they don’t want their families to know,” he says. “Some of them have families out of town; they’d be mortified if they found out a loved one was homeless.”

After two and half decades, Rick still understands the temptation many of us have to look past the poor. “There’s an awkwardness when you encounter somebody who’s maybe panhandling or sitting around. And we all kind of do that little dance around them, and we don’t want to look too closely,” he says, recalling how he recently tried to avoid eye contact with someone panhandling at a stoplight. That awkwardness only intensified when he saw that the panhandling man was someone he knew. “I’m still trying to overcome that avoidance. It’s something that everybody needs to get over.”

If we can manage to get over that, Rick says, he hopes that people can graduate from “the acknowledgement of the poor to basic humane treatment.” He suggests keeping an extra bottle of water in your car to pass out, or a soft granola bar—“because a lot of these guys can’t chew very well; they don’t have good teeth.” And then, he continues, “maybe moving beyond charity to advocacy: speaking up when they’re making it illegal to sleep in your car, or banning sidewalk loitering.”

He believes in the power of looking at—and not past—the poor to gradually transform us, because he continues to experience that transformation himself. It’s why, he says, 25 years later, he’s still excited about his work with Operation Nightwatch. Rick dreams that, perhaps, a commitment on the part of everyday people to refuse to look past the poor could lead to a world without tent cities. “I don’t know what the way forward is,” he says. “I don’t know how it’s going to happen, but I believe that God’s future for us is that there’s equity and social justice and care for all human beings.”