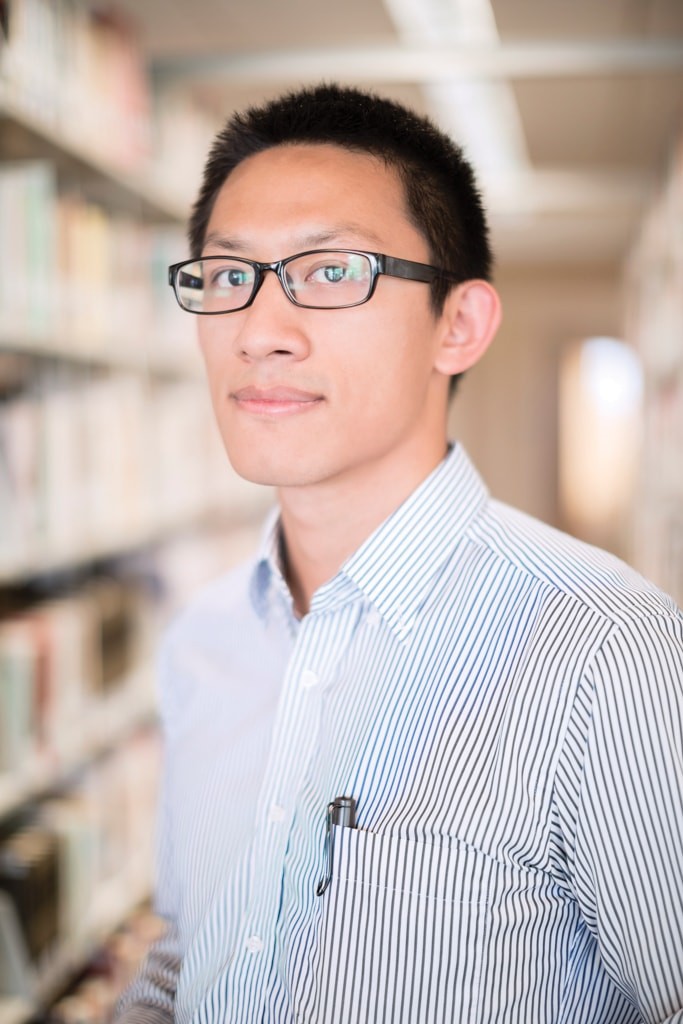

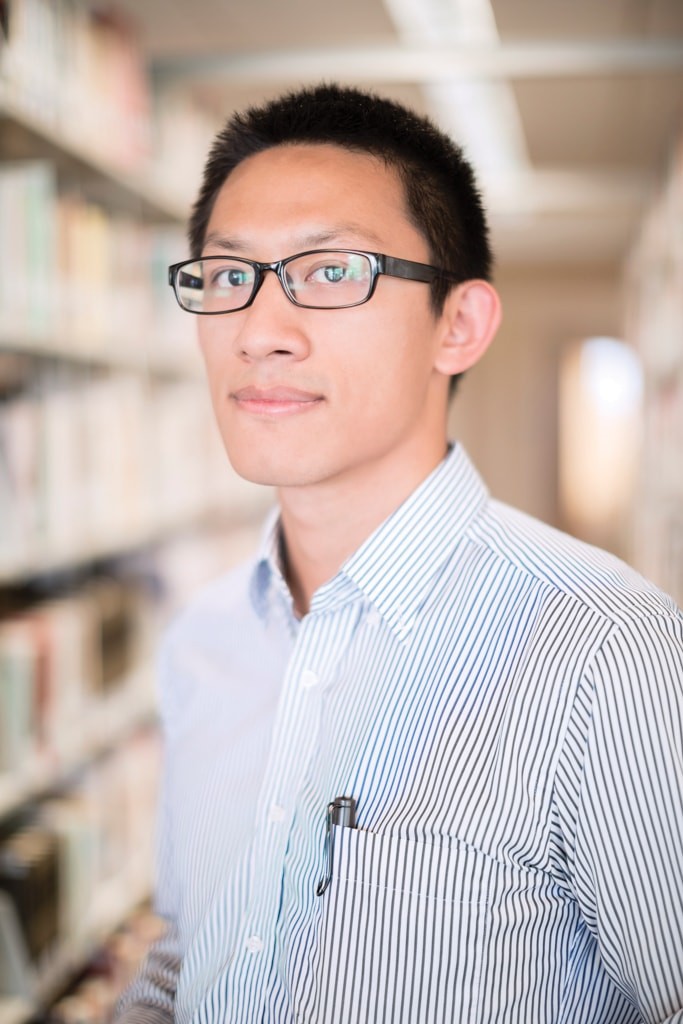

Gabriel Qi [PhD student] started reading historical novels in his native Mandarin language when he was six years old, and by the time he reached middle school in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, he had already graduated to translations of Western literature. “I wasn’t intimidated by foreign names like my friends were,” he remembers. Over the next five years, he filled his shelves with Chinese translations of Russian novels and his favorite French writer, Balzac, whose works were “an encyclopedia of different kinds of people of his time.” Gabe was following a passion for reading, but along the way he was also gaining a cultural education from books like Fathers and Sons or Le Père Goriot that helped cultivate in him an empathic understanding of others: “While we all put a lot of emphasis on the differences across cultures,” he says, “there are also a lot of commonalities that we human beings share.”

However, the reading that had exposed him to other cultures soon became a means to escape his own; Gabe was turning inward, preferring silence to relationships: “I didn’t want my relatives or mom or sister to talk to me. I preferred quiet.” It was in this deliberate silence that Gabe discovered poetry, especially the atheist poets writing after China’s Cultural Revolution. While his peers worked with academic tutors on the weekends, he was reading and writing poems with monastic discipline, filling notebooks with poems and shelves with notebooks—words that voiced his inner emotional life and stirred in him a longing for transcendence he could not otherwise name: through his writing and reading he “came to believe that there was a Ruler of creation beyond human intelligence and that humans need salvation.” Looking back, he says, it was an important season in his life—even if he’s embarrassed by the immaturity of his early work. “I just wanted to feel sad, but if I hadn’t written those silly poems, I’d still be naïve now.”

It was during a weekend trip to his cousin’s house when Gabe picked up another book that caught his attention. “There was a Bible in my cousin’s bedroom where I lived on weekends during my time at boarding school,” he recounts—a 1919 Chinese translation gathering dust in a trunk by the bed. He read six chapters of Genesis in that Bible before stopping. Looking back, Gabe calls the experience an “unexpected trigger,” drawing him out of silence and toward faith. It was the first of many triggers he experienced, and God continued to give Gabe more—often in surprising places: vulgar fictional characters who cursed God and made Gabe wonder whom they were addressing; gospel verses smuggled into the popular novel The Da Vinci Code that resonated far deeper for Gabe than the story on the surface. “Two years later, I realized that book was heretical,” he says with a sheepish grin, “but the verses from the gospel quoted in that book were profound and deep”—and strong enough to provoke his curiosity about the faith they described.

“Kun-Ming Lake”

Sky overflows the world

in pale blue watercolor,

daubing the ground by chatting reeds

a quiet thick willow

sea-foamed still water

This bank belongs to my eyes.Wind overflows another world

which belongs to my skin, hair, and eyelashes.My heart:

overflowing with one name.

Gabe took his love of literature and his interest in Christianity with him to Beijing, where he attended Peking University. “At that time I was anxious,” he says. “I wanted to be a poet, but I felt burdened to financially support my mom and sister.” While his mother encouraged him—“For now, your job is to be a student,” she told him—he still didn’t have a clear sense of where his studying should take him. He tentatively chose English, a subject that was more financially stable than poetry and more poetic than the hard sciences. “It seemed like a good compromise,” he remembers.

In one of his first English classes, Gabe learned his teacher was also a British missionary who felt called by God to teach English to Chinese students. Gabe sent him an email with a long list of questions, and they began to dialogue. “I didn’t know the difference between Jews and Christians,” he says. “It was all foreign—all different. I was asking my English teacher if I needed a circumcision!” And while he began reading Scripture again, archaic translations only added to the confusion: “Sometimes, when I didn’t understand the Chinese, I would see what the English translation said!”

Soon that professor invited Gabe to an English fellowship at a nearby church, and after he had been visiting for a few months, the congregation sang a song that struck Gabe as autobiographical:

God will make a way

Where there seems to be no way

He works in ways we cannot see

He will make a way for me.

It was an epiphany and a moment of deep relief; Gabe knew they were singing his experience. God had made a way for him—through his family who worked every day to give him time to read, through the words of writers and poets who had become his own cloud of witnesses, and through a passion for other cultures that led Gabe to study the very language filling that sanctuary with song.

It was an epiphany and a moment of deep relief; Gabe knew they were singing his experience. God had made a way for him—through his family who worked every day to give him time to read, through the words of writers and poets who had become his own cloud of witnesses, and through a passion for other cultures that led Gabe to study the very language filling that sanctuary with song.

That summer, Gabe volunteered at a camp for “leftover children” abandoned by impoverished parents who left to find work in the city. Gabe saw in their loneliness his own solitary childhood, and when they had “deep listening sessions”—a time of sharing stories and hopes—he listened carefully and shared his own experiences with them. It was a moment of empathy that triggered a new conviction: Gabe decided to become a psychotherapist. He declared a second major in psychology and, a few years later, moved from Bejing to Pasadena, where he now studies at Fuller’s School of Psychology.

He still reads all the time, but now he’s filling his shelves with books that help him integrate his wide experience into an approach to therapy: “It’s less about opinions or doctrines and more about the embodiment of love and action.” And now Gabe writes in a new way—the poetry has moved off the page into the therapy room, where he uses psalms with clients to help them translate their suffering into a language of praise.

+ Gabriel attends Fuller with scholarship support from the China Initiative—a developing program under the directorship of Professor of Religion Diane Obenchain. The initiative cultivates partnerships with the Registered Church in China and has plans to develop a master’s program fully in Chinese. This story marks FULLER magazine’s first Mandarin translation, courtesy of Gabriel Qi.

奇巍(Gabriel,在读博士生)第一次读小说是六岁时读简化版的《三国演义》,到初中时,他已经在读诸多西方小说的译本。“我不像有的朋友,一点都不觉得译过来的英文名拗口”,他回忆道。在接下来的五年时间里,他得书架上渐渐多了许多苏俄小说,以及他最喜欢的作家法国人巴尔扎克的小说。巴尔扎克的著作被誉为“法国社会的百科全书”。他读书主要是依着兴趣,不过渐渐地也从中得到了全面的文化教育,诸如《父与子》和《高老头》之类的著作让他发现人类之间所共有的体验:“我们总是特别强调不同文化间的差异,但有时却忽略了某些全人类共有的特质”。

然而不久之后,阅读所让他接触到的不同的世界成为了他逃避现实的去处;奇巍变得更内向,也更沉默:“我喜欢安静。不想听我母亲,姐姐和其他亲戚的唠叨”。也是在沉默中,奇巍开始接触到诗歌,特别是文革过后八十年代兴起的那一代中国诗人。当他得朋友们在周末上补习班时,他就开始静静地写诗,在笔记本和书架上填满让他诉说情感的文字,也让他感知到从别处找不到的超然体验:“从那时起我开始相信,这世界一定有一个主宰,超过人类的意念。而人类终究需要拯救”。回头看看,奇巍说他觉得那是人生中很重要的一段时光——即使他的诗让他有点难堪:“当时算是为赋新词强说愁,不过如果没写出有点傻的诗来,可能现在还仍然愁着。”

高中时的一个周末,他去表亲家做客,那是他第一次读《圣经》。“当时我住校,每周末去表哥家住两天。他的卧室里有一本《圣经》。我读了六章《创世记》,然后睡着了。”——鉴于那本《和合本圣经》最初翻译于1919年,文字有些古旧,这反应并不奇怪。奇巍说那是“完全没预料到的契机”,让他开始走出沉默,走向信心。而契机不止一个。讽刺的是,其中之一是许多小说中,人物的咒骂被直接翻译成“看在上帝的份上”,这让他好奇他们是在冲谁起誓咒骂。另一个则是当时非常流行的《达芬奇密码》中引用了很多福音书中得经文。“直到两年后我才意识到这本小说所讲的是异端,”他不好意思地笑笑,“但是但是真的觉得福音书里的文字那么深奥和有力!”

“西堤”

天空占据世界的十分之九,

均匀的浅蓝水彩。

剩下的是摇曳群居的芦苇,

年迈而刚健的垂柳,

水:结出海浪的湖。

它们属于我的眼睛。风占据另一个世界,

属于皮肤,头发和睫毛。至于我的心,

里面只写满一个名字。

奇巍带着他对文学的热爱和对基督信仰的好奇来到了北京,进入北京大学。“那时我很焦虑,”他说,“我想做个诗人,但是又觉得背负这撑起我的家庭的负担。”尽管他妈妈当时鼓励他说:“现在你全部的工作就是做个好学生”,他仍然不知道毕业时他回去向何方。踌躇过后他选择了医学英语的专业,经济上比学文学更有保障,文学上比商科工科来的诗意。“看起来是个不错的折中点”他回忆说。

在他最初的几门英语课中,奇巍遇到了一位来自英国的外教。外教觉得他得呼召就是到中国教书。奇巍给他发了一封邮件,问了一连串问题,他们就开始了谈话:“当时我不知道犹太人和基督徒的区别,对我来说他们都是外国人,完全不同。当时我甚至问我的老师我需要不需要去行割礼!”他又一次开始读《圣经》,虽然有些古老的和合本译文一开始有些困难:“有时候我看不太懂中文经文的意思,就读对照的英文译文”。

很快,外教邀请奇巍渠道附近一所教会的英文团契,而在定期聚会几个月后,敬拜时的一首歌曲让他深受感动。歌词唱道:

“神要开道路,

在旷野无路之处,

虽未看见祂已看顾,

他要为我开道路。”

那是顿悟和放下一切重担的体验。他知道歌中所唱的正是他得生命。神已经为他开好了道路——通过他家庭的供应让他能够每天安心读书,通过作家与诗人的文字让他读到自己的见证,也通过对不同文化的兴趣让他选择去学习那天圣所中高声赞美所用的语言。

那是顿悟和放下一切重担的体验。他知道歌中所唱的正是他得生命。神已经为他开好了道路——通过他家庭的供应让他能够每天安心读书,通过作家与诗人的文字让他读到自己的见证,也通过对不同文化的兴趣让他选择去学习那天圣所中高声赞美所用的语言。

那年夏天,奇巍作为志愿者参加了两个夏令营,其中一个的服务对象是所谓的“留守儿童”,他们的父母为了进城打工只能把孩子留在老家由爷爷奶奶抚养。奇巍在孩子们的孤独中看到了自己的童年,他们在进行“深度聆听”的活动——类似心理咨询的一个环节,大家共同分享自己的故事与梦想——时,他听得很认真,和孩子们分享了自己的经历。那时他开始渴望成为一名心理治疗师。与营会辅导以及学校的老师们咨询后,他开始修心理学双学位,也开始准备申请Fuller的心理学项目。毕业后不久,他就来到帕萨迪纳学习。

他仍然一直在阅读,不过现在塞满书架的书变成了帮助他将各种知识融入治疗的专业书籍:“意见和教条没有身体力行的爱和行为重要。”而现在他得写作有了新的形式——他的诗从纸面上移到了治疗室中,在那里他用诗篇帮助来访者把他们的苦难翻译成赞美。

+ 奇巍在Fuller的学习受到了China Initiative项目的经济资助,该项目的主任是宗教学教授欧迪安(Diane Obenchain)博士。该项目旨在通过各种活动和奖学金与中国的三自教会建立合作关系,并计划发展完全由中文授课的硕士项目