Andre Henry (MAT ’16) is an award-winning singer-songwriter, the host of the Hope and Hard Pills podcast on racial justice and social change, and the author of All The White Friends I Couldn’t Keep: Hope—and Hard Pills to Swallow—About Fighting for Black Lives. Learn more at andrehenry.co.

Jerome Blanco: I’ve seen people describe you as many things—activist, public theologian, historian, writer—and maybe some of these labels are more or less accurate than others. But you actually often respond by saying what you really are is an artist. How would you introduce yourself then and the kind of work you do?

Andre Henry: Well, I’m a singer-songwriter. And I’ve been focusing a lot on social justice in my music lately, ever since the murder of Philando Castile. I thought I knew what my music was about. It was mostly about love, you know? But I found my voice after I saw Philando Castile dying on Facebook and while I was on this journey of studying systemic racism and studying nonviolence. So that’s how I describe myself. An activist called me an “artivist” when I started writing songs about justice. I don’t like terms that combine words like that, but I kind of wish I would have gotten over myself and just said, “Okay, yeah, that’s what I am,” because it’s confusing for people. They say, “Oh, Andre’s an author, and he’s a musician, and he’s a historian.” And, yeah, it’s all connected. But the way I like to think about it is that an artist has something to say. So, I just think of myself as an artist with something to say.

JB: Can you talk more about the process of how this—the movement for Black lives—became your “something to say”? Obviously, the importance of the fight can’t be overstated, but you’ve poured so much of yourself, in every capacity, into the movement in a very active way. How did you take the steps to go in with such deep commitment?

AH: Obviously Philando Castile was not the first instance of racism that I witnessed. I grew up in Stone Mountain, Georgia, where the Ku Klux Klan was reborn, and I saw and experienced a lot growing up in an anti-Black society. One of the ways it preserves itself is by gaslighting Black people into believing that maybe we’re just being too sensitive—maybe we’re the ones being racist because there is no systemic racism. So for a long time, those things that I experienced and saw, I didn’t really feel free to say. But there was this long chipping away. It started in Bible college, when I knew that I was experiencing microaggressions, but I didn’t have that language for it. Then I moved to New York City, where it’s more liberal and where people take for granted that racism is a thing. When I started naming those experiences in New York, not so many people said, “You’re making too big a deal of it, you’re playing the race card.” It was people saying, “Yeah, totally.” Anyway, the political scene was the last straw. Hearing about Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, the list goes on. Within the same 48 hours, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. It’s still not the end. I was tired of feeling angry and helpless and powerless. And so, I decided that I needed to learn everything that I could about systemic racism, and I needed to learn everything I could about the civil rights activists who preceded us, to gain as much progress as they did. That was how that came about for me. With this line in the sand. From there, the more that I read, the more questions there were, the more there was to know. And I found myself feeling hopeful and enlightened by what I was finding. I felt like everyone in the world needed to have this information, especially the information about nonviolent struggle.

JB: What specifically pointed you to nonviolent struggle in that journey? What anchors your commitment to that way of doing things?

Andre Henry (MAT ’16) is an award-winning singer-songwriter, author, and podcaster.

Jerome Blanco (MDiv ’16) is editor in chief of FULLER magazine and Fuller’s senior content editor.

Andre Henry (MAT ’16) is an award-winning singer-songwriter, the host of the Hope and Hard Pills podcast on racial justice and social change, and the author of All The White Friends I Couldn’t Keep: Hope—and Hard Pills to Swallow—About Fighting for Black Lives. Learn more at andrehenry.co.

Jerome Blanco: I’ve seen people describe you as many things—activist, public theologian, historian, writer—and maybe some of these labels are more or less accurate than others. But you actually often respond by saying what you really are is an artist. How would you introduce yourself then and the kind of work you do?

Andre Henry: Well, I’m a singer-songwriter. And I’ve been focusing a lot on social justice in my music lately, ever since the murder of Philando Castile. I thought I knew what my music was about. It was mostly about love, you know? But I found my voice after I saw Philando Castile dying on Facebook and while I was on this journey of studying systemic racism and studying nonviolence. So that’s how I describe myself. An activist called me an “artivist” when I started writing songs about justice. I don’t like terms that combine words like that, but I kind of wish I would have gotten over myself and just said, “Okay, yeah, that’s what I am,” because it’s confusing for people. They say, “Oh, Andre’s an author, and he’s a musician, and he’s a historian.” And, yeah, it’s all connected. But the way I like to think about it is that an artist has something to say. So, I just think of myself as an artist with something to say.

JB: Can you talk more about the process of how this—the movement for Black lives—became your “something to say”? Obviously, the importance of the fight can’t be overstated, but you’ve poured so much of yourself, in every capacity, into the movement in a very active way. How did you take the steps to go in with such deep commitment?

AH: Obviously Philando Castile was not the first instance of racism that I witnessed. I grew up in Stone Mountain, Georgia, where the Ku Klux Klan was reborn, and I saw and experienced a lot growing up in an anti-Black society. One of the ways it preserves itself is by gaslighting Black people into believing that maybe we’re just being too sensitive—maybe we’re the ones being racist because there is no systemic racism. So for a long time, those things that I experienced and saw, I didn’t really feel free to say. But there was this long chipping away. It started in Bible college, when I knew that I was experiencing microaggressions, but I didn’t have that language for it. Then I moved to New York City, where it’s more liberal and where people take for granted that racism is a thing. When I started naming those experiences in New York, not so many people said, “You’re making too big a deal of it, you’re playing the race card.” It was people saying, “Yeah, totally.” Anyway, the political scene was the last straw. Hearing about Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, the list goes on. Within the same 48 hours, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. It’s still not the end. I was tired of feeling angry and helpless and powerless. And so, I decided that I needed to learn everything that I could about systemic racism, and I needed to learn everything I could about the civil rights activists who preceded us, to gain as much progress as they did. That was how that came about for me. With this line in the sand. From there, the more that I read, the more questions there were, the more there was to know. And I found myself feeling hopeful and enlightened by what I was finding. I felt like everyone in the world needed to have this information, especially the information about nonviolent struggle.

JB: What specifically pointed you to nonviolent struggle in that journey? What anchors your commitment to that way of doing things?

Andre Henry (MAT ’16) is an award-winning singer-songwriter, author, and podcaster.

Jerome Blanco (MDiv ’16) is editor in chief of FULLER magazine and Fuller’s senior content editor.

AH: It’s the type of movement that, in recent memory, has brought us this far. When you think of how racial progress happened in America, I think the first name that comes to mind is Martin Luther King Jr., right? And this is not to say that the armed struggle over slavery, and riots that have happened, and the Civil War, and those things didn’t play their part too—they have played a part. But the first name that comes to mind is Martin Luther King. And so, I was just an ordinary dude making music and wanting to do something to make a difference in the world, and I went to the first place that most people could think of.

It was actually a Fuller professor, Scott Cormode, who introduced me to the field of social movement theory, which I didn’t know existed. He told me, “If you really want to do this, then you need to really understand civil rights history.” That was my gateway into studying these things. And one book led to another. I didn’t know about Dr. King, even though he was the first person who came to mind. I started reading about the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which was more radical than the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in their views and their tactics of nonviolence. That led to me reading Gandhi, Tolstoy, all the way down the line—reading from Tolstoy opposing the Mexican-American War to stuff from the Black Lives Matter movement.

When you study the literature and study the data around nonviolence, you learn things. There’s a massive study from Erica Chenoweth that found that in the 323 conflicts they studied, the nonviolent conflicts were almost twice as likely to win. That’s by the numbers. We’re not even talking about the principle of whether or not nonviolence is better. And I don’t think that oppressed people are forbidden to use force to liberate themselves if that’s what it takes. But for me, I’ve seen the data. And the data seems to show that nonviolence has been more successful.

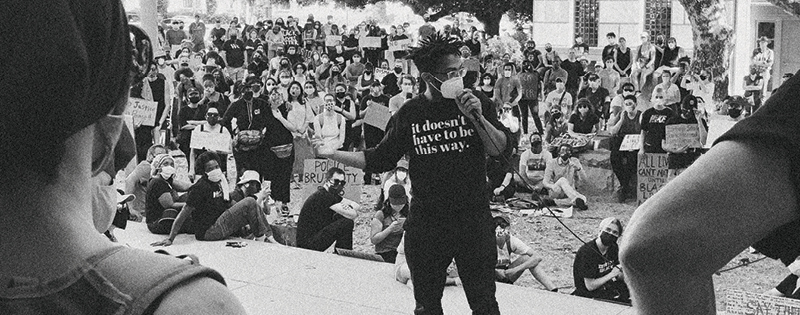

JB: You’ve really dedicated yourself to studying history—in the US and even beyond. But our society, in general, seems to have such a short collective memory. I think, for example, of all the protests in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd and where we are now, and many of our attention spans seem so short. You’ve been in it for the long haul though. What has it looked like to sustain your work even when other people’s memories falter? When many don’t remember the history? How do you deal with that and what would you teach others about that?

AH: There’s that saying: This is not a marathon, it’s a relay race. I say that to say, first off, I think it is really admirable when you look at people like Dr. King and his children and others who are lifelong freedom fighters. But that also takes a huge toll on people’s bodies and on their mental health. I’m learning now that it’s actually common for people to be very active for several years and then to basically retire. One thing that a lot of people don’t understand about social movements—but one of those things that makes them strong—is that it’s not just this reactive mobilization to some horrendous piece of news. What really helps movements to sustain themselves is building leaders. So, people who have been involved for a while need to be investing in people who are coming in so that they can learn. I am very fortunate and humbled to have people who came into the movement in 2020 and are now doing activist work in different places. They look at me and say, “Well, you taught me these things,” as I am feeling like it’s time for me to take a step back and get off the streets and heal. And I’ve invested in other people in that way. So, a part of that memory is just making sure that we keep investing in other people. We keep telling other people the stories, so that none of us feels like we have to be the torchbearer alone.

JB: That recognition that you can’t do it all or can’t do it alone makes me think of this story in your book. You write about a single mother with two sons who showed up to a protest, and that story sort of touches on the reality that the struggle involves everybody, but at the same time, there are different roles to play. This woman, for example, can’t commit to the deep study and intense work that you have done but has been a part of it in her own way. Can you say more about what that looks like?

AH: There can be like a really unhealthy culture of activism where it becomes very insular, and then it just becomes kind of a radical performance, right? Like, how are you presenting yourself as a revolutionary or a radical person? Are you making the sacrifices? Are you putting in the time? Then it just becomes about who’s got the most bruises and who’s got the least sleep and who hates the most things. A toxic version of wokeness can present itself. I’ve learned a healthier way. Not that I have mastered it—I want to be very clear that I’m not a master of a healthier way—but I’ve been exposed to healthier ways of doing this through trial and error. I’ve learned that it is legitimate to ask ourselves, “What are we capable of? What are we passionate about? What resources do we have?”

Because you’re one person. You have many commitments, and you have limited time, energy, and resources. Like you said, we can’t do everything. So, what is our role? That has to be connected to what we are passionate about. In the book, I ask, “What makes you angry?” because I think that’s a good indication of what you’re passionate about. Usually, anger is a signal that you feel like something should not be a certain way. That is a hint that maybe you have an idea of how things should be in that area. And maybe you should lean into that because on the flip side of that anger is your vision of tomorrow—as one of my mentors phrases that. Then use your gifts and your talents and your resources to work in that area.

Also at that intersection, I’m learning that your passion can also be about what you enjoy doing. In the work of Black liberation in the 1950s and 60s, women played a huge part. Without Black women involved, the movement wouldn’t have happened. But that’s not how we tell the story when we talk about the movements of the 50s and 60s. Black men are overrepresented in the way that we tell these stories. And because of that—the patriarchy—the way that we view the movement through that picture crowds out the insights that Black women brought to the movement, which did include a more holistic vision of Black liberation. I’m thinking right now of someone like Audre Lorde and her essay “Uses of the Erotic,” where she connected the dots between the fact that there is a sense of deep internal satisfaction that all of us seek in life, and that justice work needs to be connected to that deep sense of satisfaction. Our work needs to be in pursuit of that sense of satisfaction, but it can also flow out of that sense of satisfaction.

All that goes into our role. If you’re a single mom raising two boys by yourself, maybe you can’t play the same role as Dr. King, you know? But I’ve told this story many times. My friend told me about a friend of hers who offered to watch people’s kids while they went out to protest. And that is just as valid as marching in the streets because you are creating the space for others to do that work. This happened in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, too. They organized a carpool so that they could perform the boycott, right? Some people’s role was driving other people to work or to school. Some people were helping organize who’s driving. Some people were helping to organize some kind of way to replace people’s shoes. And some people were cooking meals. There are all kinds of ways that this movement has to happen.

JB: I love how you also talk about how hope comes into play in the movement. In the book, you write about the practice of having hope, and even establishing your own hope regimen. Can you talk about that a bit? When did you decide you needed to do this?

AH: It was around 2017. It was just a year after I started being active, when every single day I would wake up and ask myself, “What can I do today to try to help move this thing forward?” For a whole year, I was writing blogs, making videos, writing articles, writing songs, performing here, speaking there. I was reading and studying. I was all in, and a year later, I was already feeling, “This is so much.” Then someone sent me Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit. I read a chapter every day like it was a devotional, because it was so enlightening. I said, “I need to make sure I always have a book about hope that I’m reading.” I realized I needed to be hopeful, or else I was going to buckle under the weight. I was so depressed from doing the work that I knew I needed hope. And the only way that I’m really going to get it, I’m learning, is if I look for it intentionally. So that’s what I did, what I’m learning to do. Over the years, I’ve built a kind of self-care regimen that includes nursing my memory on the stories of people who have fought against the powers and won, also just taking care of my physical body, drinking water, getting sleep, putting my cell phone away when I sleep at night so that, when I wake up in the morning, I am more clear-headed. It’s kind of like mental hygiene. A huge part of this battle is psychological.

JB: Going hand in hand with that idea of hope is also the idea of joy. You write about that too—how you can’t just wait for the end of the suffering and the struggle to then reach the joy someday in the future. You write about the necessity of joy now, in the present. What does that kind of joy look like?

AH: I was kind of poking fun at the dynamic earlier when I said people have this idea that being a serious revolutionary means you have to be upset all the time and be this hard individual. And, okay, part of this journey of political awakening involves that seriousness. There’s a balance here though, where I think some people just become so woke—I hate using woke in a pejorative sense—they’re just no fun at all, and there’s no joy at all. And that’s not why we do the work ourselves. It makes a movement an end instead of a means of people beginning to live. People begin to behave as though the point is just for us to constantly be fighting. But the point is for us to create joy, right? We want to abolish punitive, inequitable systems so that people can experience the joy of living outside of those systems, living in the joy of being in a restorative community where communal care is our common sense and where people’s needs are met. That’s a joyful vision of the future. And people don’t realize that it’s not the disillusioned realism that makes the movement strong. Joy makes the movement strong.

*This interview has been edited and condensed for publication.

Leaders from Fuller’s Asian American Center share about a new initiative serving the Filipino American Church and the church beyond.