A (Humble) Manifesto

Evangelical mission theology and praxis is implausible in the present time unless it is attentive to the opportunities and challenges of interfaith engagement. Although we live in an increasingly secular global context, non-Christians are mostly people of faith rather than atheists or agnostics. Credible Christian mission in a religiously pluralistic world, then, must be fundamentally alert to interfaith complexities. There are three interrelated modalities and rationales for interfaith interaction: orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and orthopathy.

First, the orthodoxic trajectory foregrounds the human quest for and witness to the truth. There is a dialogical character to such witness bearing. The missional thrust of Christian and specifically evangelical faith motivates confession of Christ. Here, orthodox confession denotes less the affirmation of specific creedal formulations as the commitment to engage with religious others at the discursive level. Such “truth encounters” insist that in the meeting between people of living faiths, there are not only similarities but, more importantly, inevitable differences that identify what is at stake. Hence the interfaith encounter includes both negative and positive apologetics: the former defending the plausibility of Christian faith against the polemics of others, and the latter involving interrogation of other faith claims from the Christian standpoint. Interreligious dialogue at this level is crucial for clarifying what the interlocutors in other traditions affirm so that Christian apologetics speaks truthfully about, rather than bears false witness against religious others. At a deeper level, Christian mission in such interreligious contexts appropriately contextualizes faith claims in order to more effectively engage those in other traditions. Just as the Christian stream includes dogmatic traditions that various Christians receive differently, so also other faiths include variations that inform their adherents across the spectrum. Effective Christian witness must thus be attuned to traditional, regional, cultural, linguistic, and personal dynamics in an interfaith world.

Yet Christian enthusiasm for proclaiming and sharing the truth must be matched by their quest for truth. There is a fine line here, one that involves the Christian conviction that the truth is found in Christ on the one hand, but also recognizes that our knowledge of “the mystery of Christ” remains partial in some respects (Eph 3:4; Col 4:3; cf. 1 Cor 13:12; 1 John 3:2). While people in other faiths certainly do not testify to the truth of Christ (that is the point of non-Christian faiths), who is to say that their own quests for the truth might not also somehow refract the light of Christ that shines somehow in every heart (cf. John 1:9)?

If on the one side Christians interact dialogically with people of other faiths in order to understand them and thereby witness truthfully and effectively to them, on the other side, Christians also ought to expect nothing less than such committed approaches from others. The result would be a standoff—one in which both groups dig in their heels convinced of their own corner on the market of truth and of the others’ misguided beliefs. But Christians have theological warrant to believe both that the conversion of others is ultimately God’s responsibility and that their own transformation might indeed be mediated through substantive encounters with others. After all, as evangelical missionaries consistently testify to, participation in God’s mission involves not only witnessing to others but also being shaped by the living witness of others in turn. Hence there is not only the hope of influencing and impacting the lives of others, but there should also be every expectation that authentic interfaith interaction will result in personal transformation as well. At the more general level of communal faith identity, Christian thinking theologically, doctrinally, and constructively in a pluralistic world will then be informed by in-depth reflection on and with those in other faiths. Theology by and for the church in the twenty-first century cannot proceed in isolation as if others were absent.

Second, the orthopraxic domain focuses on the human need for and the collaborative fostering of the common good. Such missional thrusts vis-a-vis those in other faiths have both theological and pragmatic aspects. Theologically, Christian mission is increasingly being recognized as multifaceted inasmuch as Christian salvation is understood in more holistic terms. If the latter includes not only the spiritual but also the material, communal, social, political, economic, and environmental dimensions, then the former must engage deeply with these multiple layers in order for the message of Christ to be good news to the world. Christian mission participates in the redemptive work of God to heal, restore, and renew what is fractured by sin. Hence, concrete impact in many of these arenas involves bringing faith commitments into the public square. In a post-secular world, then, people of faith walk a fine line that both refuses to blur the lines between “church and state” (or synagogue and state, etc.) and yet recognizes that meaningful human efforts in the public realm cannot be achieved if homo religiosus has to check their deepest values at the door before making such contributions. If that goes for Christian believers, then it applies mutatis mutandis also to those of other faith persuasions.

Simultaneously, it ought to be recognized that people of other faiths are also motivated by their faith traditions to work for the common good. Other religious ways have nurtured human flourishing in cultures and civilizations for millennia long before our current age of globalization. The difference today is that all humans tend to draw from their own wells in order to collaborate on matters that impact the common good, not just for their own specific faith communities but for all. Response to the environmental crisis, for instance, has to be an interfaith effort, and members of the various faith traditions will need to muster all resources available to them—religious or otherwise—and then work cooperatively with people of no or any faith in order to make a difference for succeeding generations. Christian mission work, therefore, now proceeds with people of other faith rather than merely to them. On the other end, Christians also reap the benefits of the work of religious others in the public sphere.

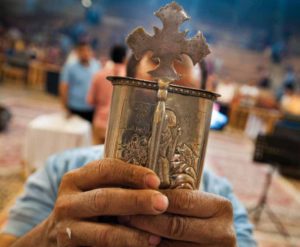

Third, the orthopathic sphere highlights the human orientation toward and desire for the beautiful. The point here is not only that other religions are also in search of the beautiful; in fact, if the glory of the new heavens and earth will be constituted in part by what kings and nations bring into the New Jerusalem (Rev 21:24, 26), it is inconceivable that such will be bereft of the beauty found in other faiths. But more importantly, what is being discussed concerns the affective dimension of the human constitution: the beautiful is what we hope for, long for, and love.

This aesthetic vision, however, can be reduced neither to cognitively construed propositions (orthodoxy) nor pragmatically resolved constructions (orthopraxis); rather, it operates at the interior level of the human will, imagination, and heart. It is for this reason that religious conversion is both about being caught up by something beyond the self (this is the point about grace) and about choosing to make a commitment (this is the point about religious freedom). Hence, at the end of any kerygmatic declaration of the gospel’s content or after any manifestation of works of mercy regarding the gospel’s commitments comes an invitation to “taste and see that the LORD is good” (Ps 34:8 NRSV). Christian testimony (orthodoxy) and holistic witness (orthopraxy) here culminate in an appeal to the heart (orthopathy).

But herein lies the deepest and most profound challenge for Christian mission in a pluralistic world. If the beauty of Christian faith derives from its being experienced by others, so also is the beauty of other faith traditions incomprehensible apart from some kind of performative engagement with them. Just as the mysteries of the incarnation and the Trinity are captivating only to those who have immersed themselves in a lifetime of spiritual disciplines, so also the beauty of other faith traditions are fully available only to those who have walked in those pathways. Yet evangelicals cannot give their hearts to other faiths in these ways for that would be akin to selling their souls to other deities (the temptation to idolatry). However, in the image of the triune God who sent his Son incarnationally into the far country and poured out his Spirit pentecostally upon all human flesh, so also are Christians invited to be both hosts to and guests of those in other faiths. In the former role, Christians welcome those in other faiths to experience the gracious hospitality of the triune God; in the latter role, Christians enter into other ways of life following in the footsteps of Jesus and empowered by the Spirit who enables human solidarity across otherwise constructed boundaries (i.e., of race, gender, class, culture, language, and even religion). While hosts maintain a certain level of control over the (interfaith) environment, guests are vulnerable amidst the parameters established by others. Evangelical Christians will disagree on how much to risk in venturing affectively, performatively, and practically along the road with their neighbors of other faiths. Yet their own faith commitments suggest that their own transformation in the process pales in comparison to the glory to be revealed in the grand scheme of things when and where all creatures—“us” Christians and “them” of other faiths—are guests in the beautiful presence of the triune God.