Dialogue, Cooperation, Conversion

Interfaith engagement is a serious business. People who want to be involved in it need to be willing to take up the challenges that the community of one faith presents to the other community. A genuine and meaningful engagement will necessarily lead to witnessing to one’s faith while fully respecting the other one. Christian partners in interfaith engagement must first consider a threefold challenge that Jesus himself demonstrates with his disciples in the Sermon on the Mount. Understanding this example then will enable us to address the following threefold challenge of Islam: theological, political, and missionary.

The Threefold Challenge of Jesus to His Disciples

In Mathew 7 Jesus puts to his followers a threefold challenge that can be defined as follows. First he demands that they take a critical look at themselves (vv. 1–5). This includes scrupulously examining our turbulent history with Muslim peoples, our divisions, and even our theologies. Second, Jesus advocates taking a critical look at other faiths (vv. 15–20). Once we have accepted to see ourselves in the mirror, we are probably better equipped to assess Islamic doctrines and claims, without being judgmental or arrogant. Third, Jesus advises the disciples that they not be deluded about their faith; if it doesn’t lead to obedience to God’s will, it is useless (vv. 21–23). Evangelical Christians who rightly believe that salvation is by God’s grace through faith often overlook those New Testament texts that highlight the need to produce good deeds to authenticate faith. This is one of the main points Jesus makes in the parable of the sheep and the goats (Matt 25:31–46).

The Golden Rule for interfaith engagement is this: “In everything do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets” (Matt 7:12). This means respecting Muslims as human beings and as religious people, appreciating their monotheistic faith, studying Islam without prejudice as much as possible, removing misunderstandings and building bridges between the two faiths, but also acknowledging their differences, even their contradictions. It also entails explaining the Christian faith without denigrating Islam, seeking to commend the truth of the gospel to Muslims in a way that fully honors their freedom of conscience, being open-minded and willing to learn from others, staying humble and acknowledging one’s failures, and appealing to God’s mercy for all of us—Christians, Muslims, Jews, people of any faith and of none.

- The Theological Challenge: Understanding Islam

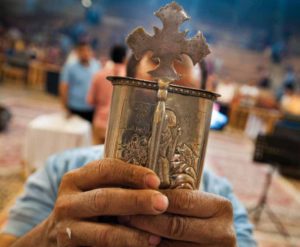

Engaging theologically with Islam involves considering Islamic teaching, the prophetic credentials of Muhammad and the status of Islamic Scriptures. For Muslims the core of Qur’anic teaching is found in the first sura, al-Fatiha, seen by Muslims as the greatest sura. Muslims say this prayer seventeen times a day during their five ritual prayers.

Islamic teaching encapsulated in Al-Fatiha (Qur’an sura 1)

In the Name of God/The Ever-Merciful, the All-Merciful/Praise be to God/The Lord of the Worlds/The Ever-Merciful, The All-Merciful/King of the Day of Judgement./You alone we worship/And You alone we ask for help./Guide us on the straight path,/The path of those who enjoy Your grace,/who are not under Your wrath,/and who do not go astray./Amen

To be fair to Islamic faith we need to understand it the way Muslims do, not the way we often tend (or even desire) to see it. Are there any parts in this prayer that Christians cannot accept? How does it compare with some of the Old Testament Psalms? As a monotheistic faith, Islam is remarkably similar to Christianity. Christologically, however, the two faiths are irreconcilable, as the Islamic account of Jesus Christ makes no room for his divinity and for his historical death and resurrection.

Muhammad

Muslim scholars put forward four main proofs for Muhammad’s prophethood: his miracles of which the Qur’an is the greatest, the perfection of Islamic law, the fact that Muhammad was foretold in the Bible, and his military achievements. These proofs are not compelling when carefully examined from a Christian perspective, which explains why Christians do not accept Muhammad as a prophet, let alone the greatest and the last prophet. Having said this, Muhammad was undoubtedly a great religious, social, and political reformer.

Many Christians examine Muhammad’s career in the light of Jesus Christ’s mission. They blame the Prophet of Islam, among other things, for his military career and his many wives. But they forget that in the Old Testament we find many polygamous prophets (including Patriarch Abraham and King Solomon). We also find violence carried out by respected prophets (e.g., David conquered Jerusalem through a holy war in 2 Samuel 5:6–10, and Elijah slaughtered four-hundred-and-fifty false prophets in one day, 1 Kings 18:40).

The Qur’an

The fact that Muhammad cannot be seen as a prophet from a Christian point of view means the Qur’an cannot be considered God’s word either. This does not imply, however, that we have to reject the Qur’an completely. A balanced approach to the Qur’an (see 1 Thess 5:21–22) has to take into account both the similarities and the differences between the Qur’an’s and the Bible’s messages. There are truths in the Qur’an, and we need to identify them and see how they relate to those in the Bible.

- The Political Challenge: Working with Muslims

Muslims are first and foremost our fellow human beings. Those who live in our country are also our fellow citizens. As fellow monotheistic believers, they are God-fearing people as well. The parable of the Good Samaritan invites us to see them as our neighbors and to love them as ourselves (Luke 10:25–37).

The political challenge should be understood in the sense that we need to work with Muslims for the common good of the city (“polis”), of our society, for the benefit of people of all faiths and of none. Rather than ignoring our faith identity, we need to make the most of the commonalities between our faiths in order to enhance cooperation. After all, we have received from our Creator a similar mandate, and we are called to fulfill this mandate with all our fellow human beings, including Muslims, based on our shared values.

Our God-Given Mandate

Christians and Muslims see themselves as God’s servants whose duty and privilege is to obey their Creator, to worship him, to acknowledge his greatness, and to bear witness to him and to his mercy, forgiveness, justice, sovereignty, and so forth. We have been honored by God who appointed all his human creatures as stewards over his creation and his representatives on earth (in Arabic, caliph). Our task is to rule over and to look after God’s creation (see Gen 1:27–30; Qur’an 2:30).

Our Shared Moral Values

The values that Christians and Muslims have in common are numerous and include the following: respect for human life from beginning to end; sexual chastity for unmarried people; marital faithfulness for couples; family life; and solidarity with our fellow human beings, especially the most vulnerable, including children, orphans, the poor, widows, the elderly, travellers, strangers, the sick, disabled, jobless, prisoners, and so on (see Qur’an 2:177; 9:60; 76:8–9).

- The Missionary Challenge: Witnessing to Christ

Working hand in hand with Muslims to further the cause of justice and peace in society and in the world doesn’t mean ignoring the distinctives of our respective faiths. For Christians it means bearing witness to Christ in a context where this witness is more likely to be heard, understood, and hopefully received.

Some Christians are inclined to ask questions such as, Do Muslims really need to know the gospel? Isn’t Islam as good for Muslims as Christianity is for Christians? Should the gospel be shared with Muslims? To the extent that the Islamic Jesus is no more than a prophet, it is our duty and joy as Christians to make known—as well as the right of all Muslims to have the opportunity to know—that Jesus is much more than a prophet; he is the Savior of the world.

Muslims expect Christians to live up to their faith and not to shy away from the teaching of Christ. What they do not want us to do is to share the gospel arrogantly, using unethical means including despising and demonizing their religion, seeing them as target for evangelism, and the like. Before he ascended to heaven, Jesus Christ appointed all his disciples to be his witnesses (Acts 1:8). We may not be gifted evangelists or preachers, and we are not all called to be missionaries. Yet Jesus Christ wants all—not just a few—of his disciples to be involved in mission. Ordinary but committed Christians are key to Christian mission. The Great Commission (witnessing to Christ) must be carried out within the context of the Great Command (loving our neighbor). Effective Christian witness needs to be holistic. In its mission statement, World Vision, a Christian development and relief NGO, defines Christian witness comprehensively as follows: “[We bear] witness to Jesus Christ by life, deed, word and sign that encourage people to respond to the Gospel.”

If (or when) people respond positively to the gospel, they become followers of Jesus Christ. Thus, conversion is to be seen as an expected outcome of interfaith engagement. It is important for new converts to remain loyal to and active in their community in order for them to witness to their family and society. They need to remain positive in their relationships with their culture and not to offend their people unnecessarily.

In summary, theological dialogue is an important aspect of interfaith engagement. It is meant to gain a better biblical understanding of Islam and to make it easier for Christians to engage in more practical ways with Muslims as fellow citizens and God-fearing people, for the good of the wider community. “Political engagement” represents the context that is likely to lead to spiritual sharing as the uniqueness of Jesus Christ can be explained to Muslims starting with his Qur’anic portrait as a stepping stone to understanding his full revelation as disclosed in the New Testament.