Countercult Heresy-Rationalist Apologetics, Cross-Cultural Missions, and Dialogue

For about a decade, evangelicals ministering to “cults”1 have developed divergent camps based upon very different understandings of these religious groups and what constitutes appropriate responses to them. After introducing new religious movements in the context of cultural trends, I will respond to them using three approaches: a heresy-rationalist apologetic, the lens of cross-cultural mission, and dialogue. Along the way, my advocacy for cross-cultural mission and dialogue will be evident in my analysis and critique. I will conclude with thoughts that evangelicals can use for further reflection on these methodologies in ministry.

“Cults” and New Religious Movements

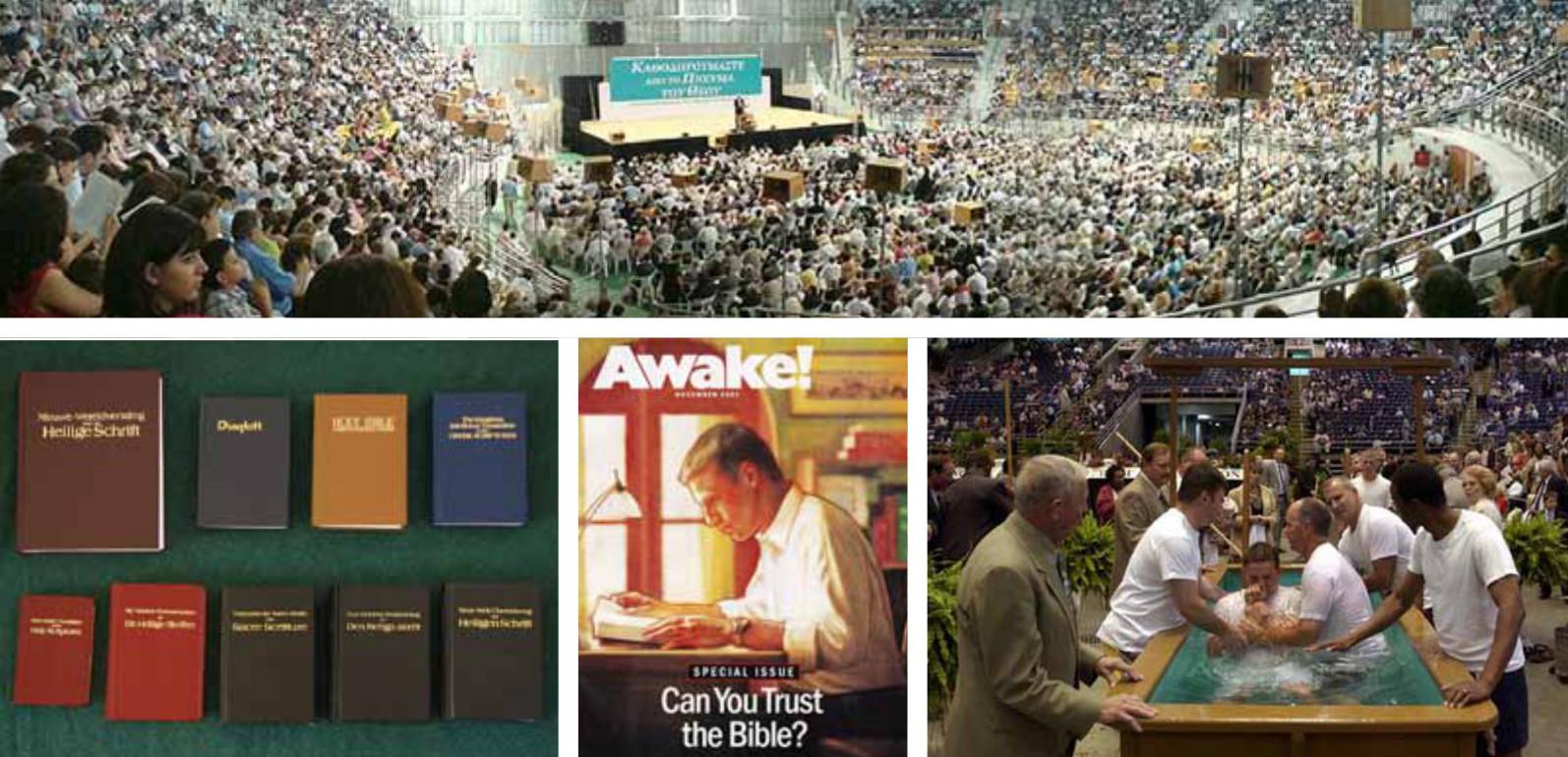

Although Christianity has been and continues to be the dominant religion in the United States, the religious landscape has also been home to a number of “cults” or new religious movements.2 A survey of the material produced by evangelical “countercult” ministries, which specialize in these groups, reveals that a large number of new religions are addressed, but only a select few receive attention in any great detail. These include Mormonism and Jehovah’s Witnesses as well as “the occult” and “New Age.” The group’s perceived danger to the church appears to be the criteria that determines which ones receive attention and critique.

Stepping back a bit for perspective, evangelicals should keep in mind that the samples of new religions addressed by the countercult ministries are not the only new religions or alternative forms of religiosity in America or in the West. In addition to the Bible-based groups like the Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses, we should also be aware of the Western esoteric tradition,3 which includes various forms of Pagan spirituality. In addition, increasing numbers of people are now pursuing an eclectic do-it-yourself spirituality that eschews institutional religion and draws upon any number of religions and spiritualities in a consumer-driven cafeteria style. This overlaps with the much-discussed demographic segment called “the Nones,”4 those who responded to recent surveys on religious affiliation by claiming no connections to institutional religious bodies. The responses of such individuals are best interpreted5 as part of the continuing trend towards dissatisfaction with institutional religion and preference for an individualized spiritual quest.

With this broader perspective in mind, although the new religions represent only a small part of America’s religious makeup, they are greater in number than often recognized, and only a handful of them receive the special attention of evangelicals. Even so, while their numbers are small comparatively speaking, they are religiously and culturally significant. In our new spiritual marketplace, as Christopher Partridge has noted, “New religions and alternative spiritualities should not be dismissed as the dying embers of religion in the West, but are the sparks of a new and increasingly influential way of being religious.”6

With this broader perspective in mind, although the new religions represent only a small part of America’s religious makeup, they are greater in number than often recognized, and only a handful of them receive the special attention of evangelicals. Even so, while their numbers are small comparatively speaking, they are religiously and culturally significant. In our new spiritual marketplace, as Christopher Partridge has noted, “New religions and alternative spiritualities should not be dismissed as the dying embers of religion in the West, but are the sparks of a new and increasingly influential way of being religious.”6

New Religions and the Evangelical Movement

Historically, countercult concerns over the new religions can be traced back to the early 1900s to the work of William C. Irvine. In his historical analysis of the countercult, Gordon Melton discusses the 1917 publication of Irvine’s book Timely Warning, later reprinted in 1973 as Heresies Exposed, as a book that would later pave the way for opposition towards “cult” groups as threats to Christianity.7 Prior to this, in the nineteenth century, other groups had been opposed as heresies, such as Spiritualism, Christian Science, and Seventh-day Adventism, with Mormonism standing out as the recipient of some of the greatest attacks. Melton notes in this regard, “Anti-Mormonism became a popular ministry among Protestant bodies and to this day provides the major item upon which evangelical countercultists apply themselves.”8

The number of heretical concerns multiplied over the course of the nineteenth century, and various books were produced in response. With the arrival of the twentieth century, modern liberal Protestantism came to be seen as the new threat. Fundamentalist Protestants mounted a defense by affirming various doctrinal essentials contra liberalism, such as the Trinity and the Virgin Birth of Christ. In the context of this struggle, the next major figure arose in Jan Karel Van Baalen. His book Chaos of Cults (1938) covered a wide variety of groups and provided a doctrinal refutation of their teachings by way of an appeal to the authority of the Bible. Melton notes that this volume went through numerous reprints and revisions, and its presence coincided with the end of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy in 1930. Evangelicalism would arise as part of the fallout from this battle, and with it, “Evangelicals sensed a need to draw even stronger boundaries to their community than Christianity in general.”9 This set the cultural and religious context for the rise of Walter Martin, who raised the bar for Protestant concerns about the threat level posed by heretical groups. In Melton’s view,

The number of heretical concerns multiplied over the course of the nineteenth century, and various books were produced in response. With the arrival of the twentieth century, modern liberal Protestantism came to be seen as the new threat. Fundamentalist Protestants mounted a defense by affirming various doctrinal essentials contra liberalism, such as the Trinity and the Virgin Birth of Christ. In the context of this struggle, the next major figure arose in Jan Karel Van Baalen. His book Chaos of Cults (1938) covered a wide variety of groups and provided a doctrinal refutation of their teachings by way of an appeal to the authority of the Bible. Melton notes that this volume went through numerous reprints and revisions, and its presence coincided with the end of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy in 1930. Evangelicalism would arise as part of the fallout from this battle, and with it, “Evangelicals sensed a need to draw even stronger boundaries to their community than Christianity in general.”9 This set the cultural and religious context for the rise of Walter Martin, who raised the bar for Protestant concerns about the threat level posed by heretical groups. In Melton’s view,

“It is easiest to see the countercult movement as it emerged in the 1950s as a boundary maintenance movement that found its dynamic in the Evangelical movement’s attempt to define itself as an orthodox Christian movement while rejecting its imitators and rivals.”10

Although several decades have passed since the fundamentalist-modernist controversy and the birth of the countercult as a boundary-maintenance movement, evangelicalism retains a strong sense of both its boundaries and the need to defend them from perceived enemies. Jason Bivins views evangelicalism as a religion that is combative and “preoccupied with boundaries,”11 including the line between orthodoxy and heresy. The skirmishes over this particular boundary marker are played out, in this writer’s estimation, through the construction of an evangelical faith identity that includes a combative posture towards other religions, particularly the new religions.

Countercult Heresy-Rationalist Apologetics

Evangelicals have utilized a variety of approaches in responding to the concerns posed by the new religions. After surveying countercult literature, Philip Johnson identified six basic apologetic models.12 By far, the dominant model is what Johnson labels the “heresy-rationalist apologetic.” This approach uses a template of systematic theology and apologetics that involves doctrinal contrast and refutation. Doctrines understood as central to evangelical Christianity, such as the nature of God, Christology, and soteriology, are contrasted with the corresponding views or their assumed counterparts in the new religions. When the doctrinal perspectives of the new religions are found to be incompatible with Christianity, a biblical refutation is offered. In addition, this approach can also include apologetic elements that seek to find the rational inconsistencies or shortcomings in the worldviews of the new religions. The emphasis on orthodoxy versus heresy, and the inclusion of apologetic refutations of competing worldviews come together to form the heresy-rationalist apologetic approach.

Johnson notes that this analytical grid of heresy versus orthodoxy has historical precedent, such as Van Baalen and others who were significant in utilizing this methodology.13 But in terms of the person responsible for cementing these ideas into the fabric of evangelicalism, it is difficult to overestimate the significance of Walter Martin.14 He had a direct or indirect influence on much of the countercult, and his books and presentations using the heresy-rationalist apologetic have also shaped much of the pastoral and popular evangelical theological and methodological assumptions about the new religions.

The positive elements of the heresy-rationalist apologetic should be acknowledged. Johnson points out15 that it excels in helping Christians develop discernment in regard to orthodox and heterodox doctrine: it involves a high view of Scripture in terms of its authority and inspiration and teaching; and it can provide teachers and other members of the church with the tools necessary to warn of heresy and maintain doctrinal integrity. Johnson goes on in his analysis to provide several examples of exemplary books of both an academic and popular nature that have utilized this approach.

Cross-Cultural Missions to New Religions

However, the heresy-rationalist approach is not without its shortcomings. In 2004, an international group of evangelical scholars and mission practitioners met in Pattaya, Thailand, as part of the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization. One of the issue groups, IG #16, was devoted to the study of new religions. Issue Group #16 produced one of the more extensive Lausanne Occasional Papers (LOP 45) to come out of this gathering, and it included critical interaction with the heresy-rationalist apologetic.16 In this paper, the group concluded that several elements “make doctrinal analysis unsuitable for use as the sole or primary method for evangelism to new religions.”17 These include the following:

- A confrontational style of argument that fails to build bridges and confidence between the messenger and recipient

- Utilizing the wrong set of biblical texts that rebuke false prophets and teachings in the church and applying them to groups outside our ecclesiastical walls

- Inappropriately drawing upon Jesus’ rebukes of the religious leaders within his own religious tradition as a model for evangelistic communication with those outside the church

- The focus on rational arguments without a relational context that includes caring and respect for other individuals

- Lack of field-tested practical advice and the use of “armchair strategies” without recourse to the sensitivities needed to communicate beyond offering apologetic arguments18

Many of the individuals involved in this issue group had each previously wrestled with their concerns about the heresy-rationalist approach long before participating in the meeting in Thailand. Although they had taken different routes along the way, fresh biblical, theological, and missiological reflection, interactions with the academic literature on new religions such as that from the social sciences, and personal encounters and relationships with those engaged in the spiritual quests of the new religions were all important parts of this process of critical reflection.

As a result of this critical process, new approaches were developed that drew upon biblical examples that contextualized the gospel message, case studies in the history of Christian mission, and the discipline of cross-cultural missiology. This resulted in a conceptual shift wherein the new religions were understood primarily as dynamic religious cultures19 rather than deviant systems of heretical doctrine. This change of perspective from cults to cultures coupled with concerns about the heresy-rationalist apologetic led to the formation of new missions approaches, examples of which are included in the 2004 Lausanne Occasional Paper. Additional examples and more extensive treatments can be found in the book Encountering New Religious Movements.20 This volume involved a number of the people connected to the Lausanne group on new religions, and its articulation of a cross-cultural mission model for engaging new religions resulted in a Christianity Today Book of the Year Award in the category of Missions/Global Affairs. It has also received positive reviews in academic theological and missiological journals and websites.21

Lausanne Issue Group #16 met again in Hong Kong in 2006,22 and again at Trinity International University in 2008.23 As a result of the Trinity consultation, Perspectives on Post-Christendom Spiritualities was published, which included the contributions of several participants.24 The development and utilization of cross-cultural mission approaches to new religions continues and now represents a significant alternative to countercult apologetic approaches.

Objections to the Missions Approach

The development of cross-cultural mission approaches to new religions has not been well received in all segments of evangelicalism. Given that the model was developed in part as a critique of the countercult and their use of a heresy-rationalist apologetic, it is not surprising that individuals within the movement have been its most vocal critics. Although no countercult spokesperson has published an essay in a peer-reviewed journal critiquing the mission approach, I have had email exchanges in years past with some of these individuals. As a result of these conversations, some of their main objections to the mission approach are summarized below, followed by my brief responses.

Inaccurate representation of the countercult. One common objection is that the critique offered of countercult ministries and methodology is not accurate and is based on misunderstanding. In response, we should recall the extensive academic research into the countercult done by figures like Johnson, Melton,25 Cowan,26 and others. In addition, many now involved in cross-cultural mission approaches were formerly involved in countercult ministries and at one time utilized heresy-rationalist approaches themselves. It is difficult to see how this depth of research and experience with countercult methodology could lend itself to such gross misunderstanding.

Mission approaches are already being done by the countercult. Another objection is that countercult ministries are already doing cross-cultural mission work, and thus these “new approaches” really represent nothing new. However, a careful comparison of the heresy-rationalist apologetic with cross-cultural mission approaches reveals a sharp contrast, as even one secular scholar has been able to discern.27

Biblical texts appropriate for Christian heresies. Countercult critics also take issue with the allegation that the wrong set of biblical texts are utilized in a heresy-rationalist apologetic. In their view, when these texts are applied to Bible-based groups, or to those heretical systems that arose within the Christian community, the application is appropriate. However, this argument still does not address the basic hermeneutical issues of the orthodoxy versus heresy template raised in the initial criticism of the heresy-rationalist apologetic. In addition, the biblical texts used by the countercult are not restricted to Christian heresies, but are also applied to those new religions such as the “New Age,” Transcendental Meditation, and the International Society of Krishna Consciousness.

Heresy-rationalist apologetics wins converts, so why consider an alternative? One final argument from countercult spokespersons is that the heresy-rationalist apologetic is an evangelistically pragmatic one—that is, it results in converts. In response, it should first be noted that such claims are anecdotal. No scientific survey data has been done in connection with countercult methods and the disaffiliation and reaffiliation journeys of those in new religions. Second, the complex and multifaceted personal journeys of former members of new religions must be taken into account. Apologetic arguments do have value, but they would seem to be most effective when individuals have already begun to make an exit. Such individuals are looking for dissonance reduction and justification as to why a religious migration towards Christianity would be a more appealing alternative.

Although I have noted the positive aspects of discernment and apologetics, in addition to the shortcomings described above, it is also ethically problematic. Penner has expressed concerns about various forms of “apologetic violence.” He defines one form as “a kind of rhetorical violence that occurs whenever my witness is indifferent to others as persons and treats them ‘objectively’—as objects—that are defined by their intellectual positions on Christian doctrine or are representatives of certain social subcategories.”28 The heresy-rationalist apologetic fits within this definition and raises ethical issues for consideration.

Furthermore, the use of heresy-rationalist apologetics as an evangelistic methodology is pragmatically flawed. It is far more likely that the use of apologetic confrontation as evangelism shuts down openness rather than creating opportunities for fruitful witness. In the view of new religions scholar John Saliba, apologetic confrontation “is neither an appropriate Christian response nor a productive social and religious reaction to the rising pluralism”29 of our time. I concur with this and with his further conclusions that “apologetic debates rarely lead unbelievers or apostates to convert; they do not succeed in persuading renegade Christians to abandon their new beliefs to return to the faith of their birth. Harangues against the new religions do not lead their members to listen attentively to the arguments of zealous evangelizers. On the contrary, they drive them further away and elicit similar belligerent responses.”30

Dialogue and the New Religions

Evangelicals have been involved in interreligious dialogue with the world religions for many years,31 but dialogue with the new religions has been rare. Melton mentions meetings between Christian leaders and the Unification Church in the 1970s, as well as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness in the 1990s.32

The most extensive dialogical interactions by evangelicals with the new religions have been discussions with Latter-day Saints. In 1992, former Mormon and Denver Seminary student Greg Johnson shared the writings of Brigham Young University professor Stephen Robinson with Craig Blomberg.33 Robinson and Blomberg went on to develop a relationship and begin a series of discussions that led to the publishing of How Wide the Divide? A Mormon and an Evangelical in Conversation.34 This became a catalyst for a variety of developments that began the process of dialogue between evangelicals and Mormons. Richard Mouw worked with another BYU professor, Robert Millet, to begin a series of conversations between evangelical and Mormon scholars. These dialogues are ongoing. After graduating from seminary, Greg Johnson founded Standing Together in Utah and began a series of public dialogues with Millet in a variety of venues. These and other dialogues between evangelicals and Mormons have also spawned new books35 providing those unable to witness the dialogues with a sense of the nature of these interactions.

The most extensive dialogical interactions by evangelicals with the new religions have been discussions with Latter-day Saints. In 1992, former Mormon and Denver Seminary student Greg Johnson shared the writings of Brigham Young University professor Stephen Robinson with Craig Blomberg.33 Robinson and Blomberg went on to develop a relationship and begin a series of discussions that led to the publishing of How Wide the Divide? A Mormon and an Evangelical in Conversation.34 This became a catalyst for a variety of developments that began the process of dialogue between evangelicals and Mormons. Richard Mouw worked with another BYU professor, Robert Millet, to begin a series of conversations between evangelical and Mormon scholars. These dialogues are ongoing. After graduating from seminary, Greg Johnson founded Standing Together in Utah and began a series of public dialogues with Millet in a variety of venues. These and other dialogues between evangelicals and Mormons have also spawned new books35 providing those unable to witness the dialogues with a sense of the nature of these interactions.

More recently, dialogue partners from the new religions have expanded beyond Mormonism. Evangelicals have reached out to the Pagan community with an eye toward developing relationships and ongoing conversations,36 and as a way of moving beyond the hostility of the past in order to form a new paradigm for interfaith dialogue37 and religious diplomacy.38

More recently, dialogue partners from the new religions have expanded beyond Mormonism. Evangelicals have reached out to the Pagan community with an eye toward developing relationships and ongoing conversations,36 and as a way of moving beyond the hostility of the past in order to form a new paradigm for interfaith dialogue37 and religious diplomacy.38

Obstacles to Dialogue with New Religions

In general, Christian dialogue with the new religions has faced many obstacles, several of which Saliba has discussed. Two stand out as especially significant. First, he notes that many Christian approaches have been “centered around orthodoxy,” which has resulted in a theological response that “has been apologetic and dogmatic.”39 He sees this as a hindrance to what could be more fruitful approaches to dialogue. Second, Saliba notes the presence of a strong sense of distrust because Christians presuppose that the motives of those in the new religions are “dishonest and/or insidious.”40 These represent significant challenges that will have to be overcome before constructive dialogue can move forward in this context.41 In order to accomplish this, evangelicals must be self-critical about the dialogue process. As I argued in 2007 in my workshop at Standing Together’s Student Dialogue Conference on Evangelical-Mormon dialogue, evangelicals need to engage in thoughtful reflection about defining dialogue, the type of dialogue they are engaged in, its goals and the processes involved, and how this relates to evangelism and mission. In our self-critique, we must also ensure that we strike a balance so that our desires for civility in dialogue do not compromise our ability to acknowledge foundational differences with our conversation partners.

Further Issues for Reflection

In recent decades evangelicals have been experimenting with new ways of understanding and engaging those in the new religions. In my view, missional and dialogical approaches are the best way forward. I conclude this essay with a few suggestions on how evangelicals might continue to develop these methodologies further as we engage not only the adherents of the new religions, but also those of other religious traditions in our pluralistic world.

Look again at the example of Jesus. Strangely, we often fail to ask whether our way of engaging those in other religions is in keeping with the example of Jesus. Bob Robinson has made this point well in his book Jesus and the Religions.42 There he calls attention to Jesus’ encounters with Gentiles and Samaritans, and he argues that these encounters provide a very different model than the encounters of many Christians in the West. Robinson examines a great number of biblical texts, and in the case of Luke 4 he concludes that “interpretive practices that allow Christian readers either to ignore (or only to comment critically on) people of other faiths are at odds with the example and commentary of Jesus himself.”43

Adopt a Christological hermeneutic. I previously argued that the heresy-rationalist approach draws upon the wrong biblical texts as the foundation for engaging the new religions. This issue can be pressed further beyond specific texts to the implications of the New Testament’s Christological hermeneutic. Derek Flood explores this by way of the Apostle Paul’s use of the Old Testament in Romans 15:8–18. Paul quotes Psalm 18:41–49 and Deuteronomy 32:43. Flood notes that in his use of these texts, Paul edited the material so as to remove “the references to violence against Gentiles, and recontextualized these passages instead to declare God’s mercy in Christ for Gentiles.”44 Flood concludes by suggesting that “if we wish as Christians to adopt Paul’s way of interpreting Scripture, then we need to learn to read our Bibles with that same grace-shaped focus.”45 A greater attention to the New Testament’s Christological hermeneutic holds significant implications for the theological foundations of a grace-shaped engagement with new religions.

Replace a hostile faith identity with one of benevolence. I noted above that evangelicalism has a strong sense of boundaries and a preoccupation with considerations about who is in and out with regard to orthodoxy. This tendency is greatly magnified in the countercult, and it often leads to the formation of hostile faith identities regarding outsiders, particularly those of other religions. I suggest that as we reconsider the example of Jesus and adopt a more consistent Christological hermeneutic of grace and peace, we should also make new efforts at loving our religious neighbors, including those whom many consider a threat. Loving our religious neighbors as ourselves in the way of grace—even while retaining a healthy set of boundaries and concerns for sound teaching—will help transform hostile faith identities into benevolent ones.

Endnotes

1In the academic study of new religious movements there are a host of methodological issues for consideration. My focus in this essay is restricted to evangelical assumptions and perspectives. For a helpful introduction to the topic, see George D. Chryssides, Exploring New Religions (London and New York: Cassell, 1999).

2Philip Jenkins, Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). In keeping with my desires to avoid pejorative language, and in keeping with the academic literature on the topic, hereafter I will refer to these groups as new religious movements.

3J. Gordon Melton, “From the Occult to Western Esotericism,” in Perspectives on Post-Christendom Spiritualities: Reflections on New Religious Movements and Western Spiritualities, ed. Michael T. Cooper (Morling Press and Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, 2010), available at http://www.sacredtribespress.com.

4“‘Nones’ on the Rise,” The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life (October 9, 2012), http://www.pewforum.org/Unaffiliated/nones-on-the-rise.aspx.

5Elisabeth Drescher, “Does Record Number of Religious ‘Nones’ Mean Decline of Religiosity?” Religion Dispatches (October 9, 2012), http://www.religiondispatches.org/archive/atheologies/6493/.

6Christopher Partridge, “The Disenchantment and Re-Enchantment of the West: The Religio-Cultural Context of Western Christianity,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly 74, no. 3 (2002): 250.

7J. Gordon Melton, “The Countercult Monitoring Movement in Historical Perspective,” in Challenging Religion: Cults and Controversies, ed. James Beckford and James V. Richardson (London: Routledge, 2003), 102–13.

8Ibid., 104.

9Ibid., 106.

10Ibid.

11Jason C. Bivins, Religion of Fear: The Politics of Horror in Conservative Evangelicalism (London: Oxford University Press, 2008), 30.

12Philip Johnson, “The Aquarian Age and Apologetics,” Lutheran Theological Journal 34, no. 2 (December 1997): 51–60. Johnson expands on this discussion in his Apologetics, Mission & New Religious Movements: A Holistic Approach (Salt Lake City, UT: Sacred Tribes Press, 2010), available at http://www.sacredtribespress.com. Countercultists sometimes take issue with this typology and nomenclature, but John Saliba has described Johnson’s work in this area as “probably the most insightful, carefully articulated, and detailed analysis of a Christian approach to the new religious movements.” John A. Saliba, Understanding New Religious Movements, 2nd ed. (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2003), 321.

13Johnson, Apologetics, Mission & New Religious Movements, 9.

14Melton argues that Martin’s significance to the countercult is so great that its history should be understood in terms of “before Martin, Martin’s lifetime, and post-Martin developments” (Melton, “The Countercult Monitoring Movement,” 103). In addition, Saliba also references Martin’s work as exemplary among evangelical apologetic approaches to new religions (Understanding New Religious Movements, 203–39).

15Johnson, Apologetics, Mission & New Religious Movements, 11.

16Philip Johnson, Anne C. Harper, and John W. Morehead, eds., “Religious and Non-Religious Spirituality in the Western World (“New Age”),” Lausanne Occasional Paper No. 45 (Sydney, Australia: Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization and Morling Theological College, 2004), http://www.lausanne.org/en/documents/lops/860-lop-45.html.

17Ibid., 12; italics in original.

18Ibid., 12–13.

19Irving Hexham and Karla Poewe, New Religions as Global Cultures: Making the Human Sacred (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997).

20Irving Hexham, Stephen Rost, and John W. Morehead II, eds., Encountering New Religious Movements: A Holistic Evangelical Approach (Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic & Professional, 2004).

21For example, see Larry J. Waters’ review for Dallas Theological Seminary, http://www.dts.edu/reviews/irving-hexham-encountering-new-religious-movements.

Endnotes (Continued)

22Ole Skjerbaek Madsen, “New Religious Movements and New Spiritualities the Focus of the Lausanne Consultation on Christian Encounter with New Spiritualities” (February 2007), Lausanne World Pulse.com, http://www.lausanneworldpulse.com/lausannereports/02-2007?pg=all.

23Trinity Consultation on Post-Christendom Spiritualities, http://www.lausanne.org/en/about/resources/email-newsletter/archive/457-lausanne-connecting-point-november-2008.html.

24Michael T. Cooper, ed., Perspectives on Post-Christendom Spiritualities: Reflections on New Religious Movements and Western Spiritualities (Sydney, Australia: Morling Press and Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization, 2010).

25J. Gordon Melton, “Emerging Religious Movements in North America: Some Missiological Reflections,” Missiology 28, no. 1 (2000): 85–98.

26Douglas E. Cowan, Bearing False Witness? An Introduction to the Christian Countercult (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2003).

27Douglas Cowan, “Evangelical Christian Countercult Movement,” in Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America, vol. 1: History and Controversies, ed. Eugene V. Gallagher and Michael Ashcraft (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing, 2006), 143–64.

28Myron B. Penner, The End of Apologetics: Christian Witness in a Postmodern World (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2013), 132.

29John A. Saliba, “Dialogue with the New Religious Movements: Issues and Prospects,” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 30, no. 1 (1993): 54.

30Saliba, Understanding New Religious Movements, 220.

31Terry C. Muck, “Evangelicals and Interreligious Dialogue,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 36, no. 4 (1993): 517–29.

32J. Gordon Melton, “New Religious Movements: Dialogues Beyond Stereotypes and Labels,” in Christian Approaches to Other Faiths, ed. Alan Race and Paul M. Hedges (London: SCP Press, 2008): 308–23.

33Craig L. Blomberg, “The Years Ahead: My Dreams for Mormon-Evangelical Dialogue,” Evangelical Interfaith Dialogue, Fall 2012, 8–10.

34Craig L. Blomberg and Stephen E. Robinson, How Wide the Divide? A Mormon and an Evangelical in Conversation (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997).

35Robert L. Millet and Gerald R. McDermott, Claiming Christ: A Mormon-Evangelical Debate (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2007); and Dr. Robert L. Millet and Rev. Gregory C. V. Johnson, Bridging the Divide: The Continuing Conversation Between a Mormon and an Evangelical (Rhinebeck, NY: Monkfish, 2007).

36Philip Johnson and Gus diZerega, Beyond the Burning Times: A Pagan and Christian in Dialogue, ed. John W. Morehead (Oxford: Lion Hudson, 2008); John W. Morehead, “Guest Post: Pagan-Christian Dialogue, Mistrust, and a Difficult (But Needful) Way Forward,” Sermons from the Mound (March 14, 2013), at Patheos, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/sermonsfromthemound/2013/03/guest-post-pagan-christian-dialogue-mistrust-and-a-difficult-but-needful-way-forward/.

37Gina A. Bellofatto, “Evangelicals and Interfaith Dialogue: A New Paradigm,” Lausanne World Pulse (May 2013), http://www.lausanneworldpulse.com/1224?pg=all.

38For a consideration of the differences between interfaith dialogue and religious diplomacy, see my essay “Interfaith and Religious Difference: A Dialogue About Dialogue” (February 8, 2013), at Patheos Evangelical, http://www.patheos.com/Evangelical/Interfaith-and-Religious-Difference-John-Morehead-02-08-2012.html.

39Saliba, “Dialogue with the New Religious Movements,” 54.

40Ibid., 62.

41The Foundation for Religious Diplomacy has developed a set of guidelines called “The Way of Openness” that provides religious rivals and critics with a way to engage in conversations about their fundamental differences while building trust. This enables partners to engage each other in civility while maintaining a peaceful tension in their unresolvable differences. To learn more, visit http://www.religious-diplomacy.org.

42Bob Robinson, Jesus and the Religions: Retrieving a Neglected Example for a Multi-cultural World (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2012).

43Ibid., 39. Emphasis mine.

44Derek Flood, “The Way of Peace and Grace,” Sojourners, January 2012, 34–37, http://sojo.net/magazine/2012/01/way-peace-and-grace.

45Ibid.

Overview of Beliefs and Practices

1Patheos Library, “Jehovah’s Witnesses: Rituals and Worship,” http://www.patheos.com/Library/Jehovahs-Witnesses/Ritual-Worship-Devotion-Symbolism.

2Jehovah’s Witnesses Official Media Website: “Our Beliefs,” http://www.jw-media.org/aboutjw/article32.htm.

3Jehovah’s Witnesses Official Media Website: “Our Relationship to the State,” http://www.jw-media.org/aboutjw/article11.htm#neutrality.

4Patheos Library, “Paganism: Rites and Ceremonies,” http://www.patheos.com/Library/Pagan/Ritual-Worship-Devotion-Symbolism/Rites-and-Ceremonies.html.

5ReligiousTolerance.org, “Wicca: Overview of Practices, Tools, Rituals, etc.” http://www.religioustolerance.org/wic_prac.htm.

6LDS.org. “Godhead,” http://www.lds.org/topics/godhead?lang=eng.

7Preach My Gospel, “Laws and Ordinances,” p. 83. http://www.lds.org/languages/additionalmanuals/preachgospel/PreachMyGospel___00_00_Complete__36617_eng_000.pdf.

8Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Why Do We Need Prophets?” Liahona (March 2012).