Let’s pretend, for a moment, that strategic planning works. Or that the behavioral habits of your organization are consistently meeting expectations. Or that your society treats people as if they are created in God’s image. Or that your vocation, your work life, and your income are all in sync. Or that the theology you claim to believe, when practiced, has the outcomes you anticipate.

Now imagine counter-experiences. Think of situations in which carefully, prayerfully made plans failed to reach your goals. Recall situations in which the habits of your church or other organization tended to have unexpected outcomes. Consider ways your society or nation fails to treat people as God’s image-bearers. Reflect on disjunctions between the theology you claim, the theology you practice, and how God does not always meet your expectations. (Readers who take time to reflect on examples from these two paragraphs will better engage this article.)

These are ruptures—disconnects that we experience regarding thinking, acting, believing, and planning, and the subsequent consequences. We are aware how technology, or money, or health, or relationships, or organizational behaviors can be the sites of disruptions.1 Any such disruptions are disorienting and they are opportunities for critical, faithful work.2 But frequently, those who are affected by disruptions, including leaders, are likely to use tactics of avoidance—such as denial, blame, retrenchment, tighter management, increased training, and a retreat to (somewhat unreliable) habits.3 Frequently we miscategorize, perhaps labeling a problem as financial when the causes are more about deeper cultural matters, or we assume bad planning when it may be that there is a lack of emotional intelligence within a team.4 Disruptions cause us to be reactive, so we employ “fight or flight” responses that are based on the familiar scripts we tell ourselves. These scripts give us a sense of control even when that is an illusion.

While we usually think that disruptions are sudden, appearing quickly and without warning, they can actually be slow and with numerous warning signals. Climate change is disruptive, but it is not sudden and it has been coming with diverse and obvious indicators. An organization’s frameworks regarding leadership or finances or context can also be subject to slower changes that are not getting adequate attention. It is not uncommon for churches to feel disrupted when they become aware of a decades-long shift in a neighborhood’s makeup or even their own internal generation transitions.5

When there is pain and fear involved, we ask: What happened? Who’s to blame? How do we fix it? What can we do to lessen the pain? My focus is theological: How do we think about God in the midst of disruptions? My concern here is not with the problem of theodicy, regarding whether God caused, or should have prevented, some disruption. Rather, in the aftermath of a disruption, how can we engage practices that help us discern God in the resulting situation, especially regarding new options?6

The stories that Luke provides in the book of Acts show us that disruptions of all types were common as God’s reign engaged the Roman world. Luke writes about stoning, civic unrest, arrests, shipwreck, and broken relationships. A brief look at chapter 16 shows several disruptions. Paul’s mission team is diverted repeatedly by the Holy Spirit as they travel westward. They arrive in Troas, which would be considered a worthy site, but Paul has a night vision, and expectations are disrupted as a discussion leads to a new itinerary toward Macedonia. Several days of expectant explorations in Philippi lead to nothing, then a Sabbath search outside the gates brings them into a conversation with a group of women. Lydia, a businesswoman and God-fearer, engages the conversation, welcoming their message and baptism for herself and her household. Evidently the vision of a “man from Macedonia” is a woman from Thyatira! Here as throughout Acts, God is ahead of the witnesses—and the story unfolds through disruptions, surprises, experimental forays, and unexpected encounters.

It is this primary theological conviction—that God is always initiating—that needs to be at the center of our reflections about disruptions. This is not a simplistic belief that God causes everything, but rather that our agency is to be shaped by an awareness of and an allegiance to God, who is the primary agent. Whatever the nature or cause or impact of a disruption, God is always on the ground, among us, among our neighbors, initiating with love, hope, and (sometimes) judgment.7

DOING THEOLOGY IN REAL LIFE

Theology is a task, and it takes many forms. In general, theology is simply how humans think about God. Sometimes we focus on developing concepts and theories, which can take shape in creeds or systematic treaties. Sometimes we give focused attention to Scripture, trying to understand the theology of Jeremiah or Matthew or Paul. We also do our theology when we pray and worship, articulating our beliefs and longings and laments and gratitude. And even though some of us have vocational roles as professors or preachers or authors, everyone does theology—we all think about God, and then we live our lives with that thinking as one element of our thinking and decisions.8 So one important question is how well do we, as churches and as believers, do theology? And, more specific to this article, how can we do theology well in the midst of disruptions?

Recently I have had several extended conversations with a pastor who would be seen as skilled, successful, and exemplary in her roles both with the congregation and community. (I will call her Pastor Carol.) Her church has been experiencing moderate growth for most of the last two decades. Then, three years ago, several key families left in order to relocate about an hour away. They voiced their love for the church and even said they would return at times—but the frequency of those returns has decreased, and Pastor Carol encourages them to find a church nearer to their new homes. Since that year, three other key families have moved to other cities in the region, and all expressed their regrets. Each family that moved away cited the same key reason—the increasing cost of living in the church’s city. Carol also noted that the ethnic group that comprises the majority of the church has been decreasing in the city for a number of years. As the church continues its numerous activities among members and with the surrounding community, this loss has created a disruption that is calling them to new considerations and discernment.

Several years ago I was speaking with a recent seminary graduate who was the youth pastor at a large church. (I will call him Pastor James.) He was well liked by the kids, drawing teens from around the region to programs that included sports, Bible lessons, and worship practices. As he met kids in his own neighborhood, about 20 minutes from the church, James and his wife spent time driving these neighbors to the church activities. Over a couple of years the kids got a bit older and the transportation needs became more of a challenge. So at this point he faced a disruptive question that came from both the situation and his own awareness: Are there better ways to connect with these neighborhood teens than driving them to church in another community?

The disruptions Carol and James faced were rooted in particular circumstances—for Carol there was a shift in contextual realities; for James there was a shift in his awareness concerning the church’s (and his) practices of ministry and the on-the-ground situation in his own neighborhood. So the disruptive challenges included matters of context and leadership, and they both knew these were theological matters. By that claim I don’t mean we can draw a straight line from doctrines (about pneumatology, ecclesiology, soteriology) to practical answers. Rather, my claim is pointing to a basic, central affirmation of practical theology, that God is active in the context and among the people, and the work for Carol and James (and their churches) is to discern and test a way forward. I will clarify that central affirmation and describe an approach to theology that is suitable for disruptions. So, it needs to be noted, practical theology is both an academic discipline and a way of discernment for churches and leaders.9

PRACTICAL THEOLOGY AS DISCERNMENT

As an academic discipline, practical theology has emerged from a role frequently seen as subservient to other fields of study to become a field of rigorous work that refuses to separate theories from practice. At earlier times, subject areas that were considered more academic—biblical studies, systematic theology, church history—were expected to discover and formulate truths that were then applied by practitioners. This “theory-to-practice” method was even frequently adopted by those who taught in various ministry areas. As other areas of theory became valued by ministry professionals, such as psychology, sociology, organizational studies, and communications, professors and authors labored to create correlations among such disciplines. In that theory-to-practice mode, the “truths” of management or marketing or persuasion were linked, sometimes in questionable ways, with doctrines or biblical passages. This situation is the result of modernity, in which the Enlightenment’s pursuit of certainty, universal truths, and human control were enshrined in how universities sought truth,10 all based on what Pascal named as the primary wager—that life could be lived well without God.

But practical theology, as I am describing it, places God’s current initiatives (God’s actions among people and in specific contexts) at the center of our discernment. While Carol or James could develop strategies and plans without God, they know that practical theology asks a critical question in the midst of disruptions: since God is currently initiating in the contextual situation—among these people, in their daily lives—how can we discern what God is doing, and what experiments can we begin in order to participate with what God is initiating? In other words, if God is the primary agent (this is what is at stake in the theological concepts of grace, missio Dei, pneumatology, and soteriology), then central to our vocation is discernment and participation. Disruptions make this more acute, but they don’t change our calling. God is present and active, and we are invited to join.11

Rather than a theory-to-practice mode, practical theology frames our work as practice-theo- ry-practice. Actually, no one ever begins with theory; that frame is an illusion. We bring our lives—our habits of thinking and believing and behaving and feeling—with us whenever we read the Bible or ponder doctrines or consider systems for planning. All of those conceptual fields are important, so practical theology provides a way for us to gain skills in how we describe a situation, analyze numerous elements of that situation, draw on the resources of our faith, and shape next steps.

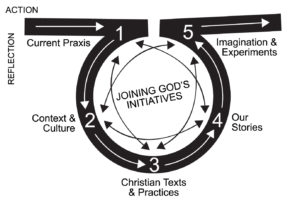

Here is an overview of the practice-theory-practice method, focused on church life but adaptable to other situations:12

1. Current Praxis: Name and describe a current praxis concerning some aspect of church life, whether some aspect of everyday life or a disruption. This work of observation and description focuses on a selected topic— such as Carol’s situation of departing families or James’ disease with his own practices— and sets some kind of boundaries for the process. It also makes you aware that you are beginning with a set of experiences and that you don’t engage study or planning as an empty slate. When possible, include multiple voices in the description and welcome divergent perspectives.

1. Current Praxis: Name and describe a current praxis concerning some aspect of church life, whether some aspect of everyday life or a disruption. This work of observation and description focuses on a selected topic— such as Carol’s situation of departing families or James’ disease with his own practices— and sets some kind of boundaries for the process. It also makes you aware that you are beginning with a set of experiences and that you don’t engage study or planning as an empty slate. When possible, include multiple voices in the description and welcome divergent perspectives.

2. Context and Culture: Analyze your praxis (the current situation and the theories and factors that are relevant). Seek to understand important influences and consequences by using resources from the culture. So, for example, this step could include the perspectives of the social sciences, history, the humanities, philosophy, studies in organizational and communication theories, along with cultural studies. Carol and James began exploring the interplay of geography, economics, and race in their contexts. This step looks in two directions: back, to understand the various influences that contributed to the current situation, and forward, to begin to imagine alternative futures.

3. Christian Texts and Practices: Study and reflect on Scripture, theology, and Christian history concerning your praxis (as described in step one) and your initial analysis (from step two). These resources of our faith, when attended to prayerfully, will help us understand our contexts and what God is doing and wants to do among us and through us. Churches can draw on their own theological heritage as well as the theological perspectives of other traditions. Like the preceding step, step three provides resources to help the group see how biblical and theological resources shaped the current situation (whether helpfully or not), and forward to imagine a potential new praxis.

4. Our Stories: Recall and discuss stories from your church’s history, your own personal lives, and the stories of your neighbors. These may be stories that note your own misunderstandings and waywardness, or you may find narratives that are full of wisdom and faith. Because we believe God is active in the church and in the context, it is important to hear diverse voices in the pursuit of discernment. As with steps two and three, step four looks back for perspectives about what influenced the current situation, and forward to new images in light of what is being heard.

5. Imagination and Experiments: Corporately discern and shape your new praxis by working with the results of steps one through four and then prayerfully naming what you believe to be your priorities. Focus on what you believe God is doing in your lives and in your context, and experiment with alternatives—not mainly for achieving successes, but to extend and expand learning and discernment. Some experiments will be affirmed and may lead toward commitments regarding new praxes.

As the figure on the opposite page indicates, I suggest a counterclockwise sequence, but in reality the process can benefit from resequencing or doubling back to a previous step, depending on what is being learned and imagined.

This process of critical reflection emphasizes that we not only consider new information but also give attention to our own assumptions, including how those assumptions need to be questioned. According to Stephen Brookfield, “Someone who thinks critically can identify assumptions behind thinking and actions, check assumptions for accuracy and validity, view ideas and actions from multiple perspectives, and take informed action.”13 This is hard work and requires that we engage the process at both the personal and group level. A leader has the work of shaping an environment in which this process can be engaged—all focused on God’s current initiatives and our (perhaps stumbling) steps as believing practitioners.14

PRACTICES OF ACTION-REFLECTION

The disruptions that Carol and James faced called them to a participatory process that brought leaders and members into new, thoughtful, prayerful steps of research, study, storytelling, discernment, and experiments. In addition to expanding their descriptions of their current situations (step one), they created teams that pursued different aspects of research (step two). Some of this was online work, but they both learned that as participants walked their neighborhoods, asking God to guide their conversations and awareness, they were drawn repeatedly into life-on-life encounters and saw how God was already at work in the lives of their neighbors. (This shows the overlap between steps two and four.) Each time their discernment teams gathered they spent time in Scripture, looking for how the Spirit would help them see connections between biblical texts and their own experiences (step three).15 Our church traditions also have resources in theology and history that can be brought into the group reflections.

Often, if the process includes learning from neighbors, step five will already have been engaged because participants needed to take steps into the neighborhood as part of their learning. Step five is about drawing together what is being learned and imagined. The goal is not a master plan but experimental next steps. Various prayer disciplines—listening prayer, prayer walks, guided meditations— can strengthen the group’s muscles for being aware of God’s more direct guidance. Sometimes this is about recall and reflection: revisiting experiences in the community or being reminded of a biblical text. Some participants may realize they need to face their own hesitations about comfort or schedules or even about whether some new learning will feel too challenging for the church. These next steps—what Ray Anderson called “experimental probes”16—make further discernment more likely because the group continues to explore God’s initiatives beyond their previous boundaries of awareness.

Sometimes disruptions require some immediate steps, but whenever possible, thoughtful and even rigorous reflection will make it more likely that the situation’s opportunities are realized. Disruptions bring loss, meaning that those who experience the interruption will experience wounds; leaders and other participants need to recognize and attend to those wounds as part of the process.

Our cultural norms emphasize strategic plans, the priority of consumer preferences, and the pastor as manager or innovator. Practical theology gives us an alternate, collaborative, spiritual mode of engaging our circumstances and contexts. Because the center of practical theology is to discern God’s presence and activities in the current situation, a fostering of awareness,17 critical reflection on assumptions, broadening of sources, careful listening, nurturing of imagination, and prayerful experiments will make faithful actions more likely. Disruptions, whatever their source, can remind us of the privilege and the work we have as those called to participate with God in God’s love for our neighbors and for us.