+ Bethany McKinney Fox, adjunct professor of Christian ethics, interviews Shane Clifton, a theology professor with quadriplegia, in a wide-ranging discussion about health and healing. Listen to more conversations curated from across the Fuller community on FULLER curated. Click here to download the entire unedited transcript of their conversation.

BETHANY MCKINNEY FOX: Let’s start with a broad question: What is health, and how do we think about it?

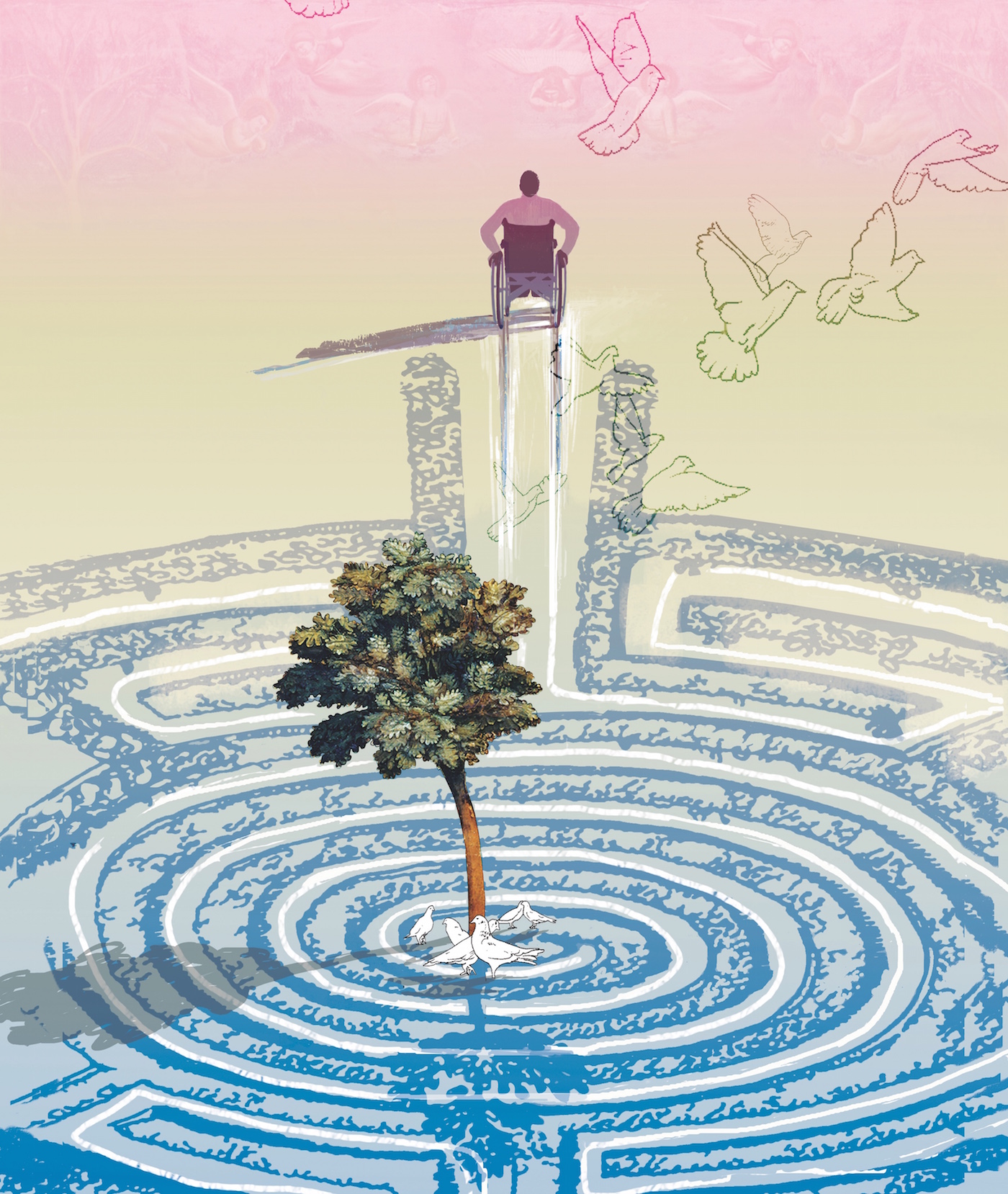

SHANE CLIFTON: Health is such a loose term and can mean different things to different people. A doctor thinks differently about health than does an athlete. My reflections on the meaning of health follow an accident I had in 2010 that left me a quadriplegic. In the years since incurring the injury I’ve thought deeply about what it means to be healthy, about why it is God hasn’t healed me, about why he caused or allowed the accident to happen at all! As time has gone on, I’ve moved my focus away from healing to contemplate what health and happiness might mean for me as a person with a serious and permanent disability. Thus my experience is my entry point into this topic.

BMF: As you’ve done research into current conversations around health, in what ways have you found those to be lacking or needing to be built upon in the work that you’re doing?

SC: When it comes to the meaning of health, it is interesting that both the church and broader society share a relatively narrow vision. In the Pentecostal community in which I teach, the focus on healing means that we understand health by reference to a perfectly functioning body. This reflects the world in which we live, which likewise envisages health in terms of the absence of illness and disability. The healthy person is fit, shapely, beautiful, and with no need to visit the doctor. The problem, however, is that this is a vision of health that none of us can attain. As a result, we all feel like failures.

I was reading Friedrich Nietzsche recently and, as you might know, from childhood he suffered from severe migraines that stayed with him his whole life. As an adult, he also experienced severe mental health challenges and cognitive decline, and he died relatively young. Drawing on this experience of ill health, he made the noteworthy observation that illness, far from being abnormal, was completely natural and, as such, normal. As a result, he says, the concept of normal health has to be given up. For him, health was a measure of resilience or strength, of the capacity to learn and grow through suffering and hardship.1

We live in a world that is so unable to treat disability or illness as normal that we can envisage only one response to prenatal disability—abortion—and only two responses to adult disability: healing or euthanasia. Thus do movies like Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby and Jojo Moyes’s Me Before You tell of supposedly “noble” suicides.

BMF: Given that the ways we think about health aren’t leading us to helpful and truthful places, how did you decide to approach this question about understanding health?

SC: I didn’t start out thinking about health. My focus was happiness. Spinal cord injury has a massive impact on life, and dealing with its losses left me unhappy. In the midst of this unhappiness I remembered the virtue tradition (I teach ethics), which is about more than morality; it’s the study of happiness. As a way of dealing with my losses—including the fact that I didn’t know what to do with my time now that surfing and golf had been taken from me—I devoured Alastair McIntyre’s various books (After Virtue and Dependent Rational Animals), and read Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Thomas Aquinas’s Summa, which all explore the relationship between virtue and happiness.2

Aristotle, for example, criticized people who pursue happiness by way of pleasure. They are slaves, he says, who live the lives of fatted cattle. He had a deeper vision of happiness, which is earned over the course of a lifetime lived in the pursuit of meaning and purpose. So, as I read about the virtue tradition and discovered new ways of conceiving of happiness, it started to change my thinking. This was a version of happiness that could be found in and through the challenges I faced with quadriplegia. Although I had lost many of the capacities that once gave me pleasure, I started to appreciate that I could live a meaningful and happy life.

It also changed the way I thought about health. I had been lamenting lost health and medical complications, but then I started to focus on what it meant to be a healthy quadriplegic. I recently came across the term “integrative health,” which recognizes that we are whole people, and what goes on in our bodies is affected by our mind and social situation, and vice versa. Health, then, is a holistic concept.3

BMF: Why not say someone can be unhealthy but still flourishing and happy? What’s the gain in expanding our understanding of health instead of just deciding health isn’t important for a good life?

SC: Health doesn’t just reference what is, but what might be. It provides a telos, a goal. But if, as a person with a disability, I am unhealthy by definition, then it’s a destructive term. An integrated vision of health moves us away from focusing on impossible perfection and toward maximizing the health of our bodies and minds and social situation. Because physical, psychological, and social breakdown are a normal part of human life, the goal of health involves living well through the ups and downs over the whole of our life.

We might use different but related terms: flourishing; the good life; the healthy, resilient, and adjusted life. In fact, the richest lives are the ones that have negotiated crisis and challenge, because it’s in the hard times that virtues emerge: resiliency, courage, generosity, and so forth. The healthy person lives well in the face of the vulnerabilities and challenges of life.

BMF: So for you, health means embracing the fragility and vulnerability that come with life—and holistic, integrative health is knowing that these things can actually lead to a different kind of happiness as they more deeply nurture virtues and character traits that lead to flourishing.

SC: Exactly.

BMF: What does it mean when we bring disability in as a focus in the conversation? Where does that take us?

SC: Disability reoriented the way I thought about happiness and health. It is a shame that disability is considered a marginal topic, rarely given central place—because when you think about life in conversation with people who have lived with disability, you have the opportunity to explore vital questions about what it means to live happily and healthily in the context of the fragility and limitations that confront us all, whether we know it or not. We are born with limited capacity, dependent wholly on our parents, and even as we grow increasingly independent, we are ever vulnerable to illness and impairment; the process of aging is itself a form of disablement.

The social model of disability also speaks volumes. The challenge of life is not just our bodily limitations, but that society disables us by creating alienating physical, social, and cultural structures. Disability is less about my need for a wheelchair and more about the fact that steps prevent me from getting inside buildings; it is less about measures of intelligence and more about education that is poorly suited to each person’s unique capacity. The social model of disability is a vital reminder that health itself is socially determined. This is, in fact, well documented; biological health is negatively impacted by poverty, sexism, racism, and disablement.

BMF: Given that we do have structures that are exclusive and disable people, what are the virtues that, as a society and as individuals within it, we need to be able to live well both individually and together?

SC: The logic of the virtue tradition is that the good life is achieved by the exercise of virtue. Virtues are habits of character that tend to facilitate success. We learn them through instruction and modeling, and the idea is to practice virtue until it becomes a habit—something we do without thinking. The fruits of the Spirit, for example, are virtues: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

I need the virtues to help me make a go of life with a spinal cord injury. I went from being an independent 39-year-old man one day to a dependent man the next, reliant on others to get out of bed, shower, get dressed, and perform countless other tasks through- out the day. I needed to learn new virtues to live well with this dependency. I’d always been an impatient person, but now I had to wait for doctors—who are always late—and for help from my family and carers to navigate my day. If I don’t respond with patience, gratitude, generosity, and the like, then I alienate my carers, and we all suffer. Likewise, I’ve had to fight to become as independent as I can, and so determination and ambition are also important virtues, acting as a vital counterpoint to patience.

BMF: As followers of Jesus, it’s worth thinking about independence: Is that a virtue we should care about? On the one hand, to flourish as individuals, as the people God created us to be, seems good. At the same time, we value the interconnectedness of the body of Christ and needing each other as a community. How much and in what ways should we prioritize independence?

SC: We live in a society where independence is everything, a trait that Christian theology has rightly critiqued. Disability is also a reminder that there is no such thing as “the self-made man.” We are all utterly dependent on one another. But there is still value in maximizing our independence. Paternalism is one of the key targets of the social model of disability. Politicians, medical practitioners, and service agencies have too often presumed that people with disabilities are incapable of individual agency. Thus there is a need to balance dependence and independence. The irony is that to maximize my independence, I might actually need more help. So independence doesn’t mean doing things on my own, but involves maximizing personal agency. Perhaps a better term might be interdependence.

BMF: Another piece that’s interesting is the connection between health and healing, because whatever we think health looks like impacts what we think healing looks like. If we are reframing health we also are reframing healing.

SC: The impact of the Pentecostal and charismatic movements on the wider church means that healing has become an import- ant aspect of global Christian spirituality. It is commonly believed that God’s love is manifest through healing, and that healing power testifies to his ongoing work in the world. This is all well and good, unless you happen to have a permanent—unhealed—disability. One of my first insights into the problem of disability and healing occurred when I attended a Pentecostal conference and found myself seated directly in front of the preacher. He spoke for one and a half hours on faith and healing, and I felt like the elephant in the room.4 To be honest, I’m becoming less and less tolerant with the way healing is taught in many churches. It seems to me many people are dishonest about healing—claiming miracles that have a natural explanation, and ignoring the truth: that most people don’t get out of their wheelchair, the blind don’t recover their sight, and many faithful people with cancer die.

This is such an important topic. If we are not careful, we add to the burden of illness and disability the crisis of failed faith. Again, it’s the broadening of my understanding of happiness, wellness, and health that has helped me to think differently about the work of God in my life.

BMF: It really would be helpful if we thought about health in this more holistic sense. If we see health in terms of happiness or flourishing as a follower of Jesus, then we would want people to be healed—but that wouldn’t necessarily mean that they are cured of their physical illness or disability.

SC: If we say that illness or disability is normal, then whatever we mean by health and healing isn’t its elimination, but living well through whatever circumstances we face. I can testify that God, in the presence of the Spirit, has helped me enormously. In that sense, we might say I’ve experienced healing power.

BMF: Given this holistic understanding of health, what are some productive ways of moving forward—practices you’d like to see in the church or for Christians in general?

SC: If we start to talk about a holistic, integrative vision of health, we can talk about the good news of the kingdom of God as the idea that God wants us as individuals, and human society as a whole, to flourish. What, then, might that mean? If flourishing involves living well, we learn its meaning through stories. It is noteworthy that the Christian gospel is a story—actually, the Gospels are given to us as four stories. It’s not a set of doctrines, but a story we are invited to be a part of. It is thus a story that adds meaning to life. So, when I think about what it means for me to live well or to pray for others to live well, it’s that we might get taken up into the joy of this larger story—and, in so doing, God will enable us to live well in the midst of the ups and downs, achievements and failures, and joys and sadness of life.

BMF: If we think about health through an integrative, holistic lens, when we read the healing narratives in the Gospels, we see that those encounters with Jesus led to a deeper kind of flourishing than just, “Oh, your eyes didn’t used to see and now they do,” or “You used to live on a mat and now you don’t.” Instead they might say, “Now you’re in a community as a follower of Jesus; you’ve been named ‘son’ or ‘daughter’ and are part of the family of God.” There are changes the whole community has witnessed and they see the person in a new way; so much more happens than just bodily healing. Each story would be only one verse long if all that mattered was that someone’s eyes weren’t seeing and then they were. Clearly, the interpretation of health that you lift up as a more holistic flourishing is also true for the people Jesus encounters and heals.

SC: You summarize it beautifully. It’s such a shame that the story of Jesus gets reduced to the simplistic formulas of faith healers. We need a bigger vision of what the kingdom of God is and what healing means.