Muslims and Christians in Ghana have always lived and shared their lives together at all levels. This shared life is both dialogical and missional. At various levels, there is cooperation for common concerns, there is the everyday living and sharing lives as neighbors from different faiths, there is the participation in theological exchange for mutual enrichment, and also there is sharing of spiritual experiences during interaction at festivals. Dialogue theologians refer to these forms of dialogue as dialogue of social action, dialogue of life, dialogue of mind, and dialogue of heart. Admittedly these forms of dialogue are only possible in a pluralistic society where there is openness to the religious other.

This article is not just about how dialogue establishes trust, mutual respect, tolerance, and hope, as important as these are. To some, this is the main goal of dialogue and anything beyond it ceases to be dialogue. My interest here is how one relates interfaith dialogue to witness (for the purpose of this discussion I prefer the term witness to mission). While dialogue is an engagement intended to change the perception of and attitude towards the religious other, witness is sharing the biblical stories with the intent of changing belief, thus inviting the religious other into a relationship with Jesus.

Dialogue theologians tell us that there are four ways to relate dialogue and witness.1 There are two so-called extreme positions: in the first, dialogue replaces witness, and in the second, dialogue is used as a means of conversion. There is also a third, middle position, which tries to keep witness and dialogue apart. However, the fourth option relates witness and dialogue dialectically, where each influences the other.2 In my predominantly Muslim context this approach is most relevant.

It is my thesis that Christian witness and dialogue with other religions are inseparable and that they are in essence two sides of the same coin. As a matter of fact, witness without willingness to engage in dialogue is arrogance, while dialogue without willingness to witness to our faith is naivety. I also believe that for both witness and dialogue to be constructive they have to be seen through the eyes of the religious other. In my work, for instance, I have not only been witnessing and educating believers to witness to their faith, but I have also been engaged with Muslims in constructive dialogue for social action. We work together to fight malaria and malnutrition in a rehabilitation center for malnourished children and in a school where we give Muslim children the opportunity to have an education. This form of dialogue is not the end in itself, but a part of the whole picture of what dialogue should be. In both these places our engagement moves beyond mere cooperation in which we understand one another, establish trust, mutual respect, and tolerance to witnessing to our respective faiths with a goal to open the other to changing one’s religious position, or if I may say, toward conversion.

A Short Autobiographical Note

Two principles can be drawn from my personal journey from Islam to Christianity and my day-to-day living in a predominantly Muslim context. In my story dialogue and witness coexist dialectically.

Born into a Muslim family, I am the eldest child of my mother, who is the third of my father’s four wives. Together with my thirteen brothers and sisters and a few dozen relatives, we shared the same house. Everyone in the family at least identifies with the Islamic faith and publicly professes the shahada. My mother comes from an African Traditional Religion background and my great-grandmother was a priestess of the village where she was born. This means that my mother has allegiance to both Allah and the god of her village. I became a follower of Christ in my early teens. Although disappointed at my change of allegiance, the family still loved me and did their best to bring me back to the family faith.

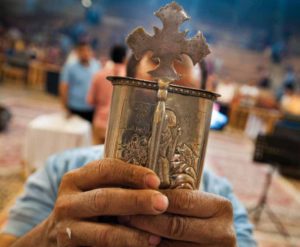

Within my family three different faiths coexist peacefully. Apart from those who strictly follow either Islam or Christianity, there are also those who practice a hybrid of Islam and the traditional religion. As a family, we celebrate our religious festivals together, share family traditions, live out our faith openly, and also each share our respective faiths with a view to possibly converting the other.3

The two principles I draw from my personal story I term the incarnational principle and the principle of reciprocity.

The Incarnational Principle

Christian witness has always been incarnational. In the person of Christ, God came to dwell among humans to serve and redeem us. Incarnation is based on relationship—one based on shared lives and traditions. Jesus’ encounters with Pharisees were both an open dialogue and a challenge to change perceptions and outlook towards others. It seems to me that in most of his encounters, Jesus not only listened but also challenged people to change.

If indeed witness is concerned with a change in belief and dialogue and is concerned with a change in attitude,4 then in my view Jesus’ ministry was both dialogical and missional. If this is the case, then the incarnation is a process of both dialogue and witness, which should be exemplified in our lives and ministry as Christians.

Principle of Reciprocity

By reciprocity I do not mean for Christians to accept the truth claim of the religious other as a precondition for dialogue to take place.5 Rather, I am referring to the admonition of Jesus that we should do to others what we would have them do to us (Matt 7:12 and Luke 6:31). These verses should serve as a guide as Christians engage with Muslims.

According to the principle of reciprocity, dialogue needs the open space for authentic witness to take place, and conversely, witness needs the open space for honest dialogue. This implies understanding the other in a way that he/she can recognize him/herself in my perception. Second, it signals bearing witness and sharing the best of one’s faith with one another. This double commandment of interreligious dialogue6 is very relevant to the way Christians relate witness and dialogue in their daily lives. We become vulnerable both towards the other’s faith as well as our own faith community. This is a necessary component because both vulnerability and conviction are part of dialogue and of Christian witness. We will only be taken seriously when we share our faith convictions and yet allow ourselves to be questioned in the same way we question the other. Both Christians and Muslims should have the right to persuade and be persuaded in dialogue while maintaining the freedom to remain firm in their religion or to change.7

Implication

In my context of living and sharing life with my Muslim family and neighbors (i.e., dialogue of life), Muslims are always zealous to call Christians and Traditional Religionists to embrace Islam. They integrate Islamic dawa (the preaching of and invitation to accept the message of Islam) in sharing their daily lives with them. This is also the case in all other forms of dialogue. For fear of causing offense, sometimes Christians fail to witness during dialogue. However, since both Muslims and Christians zealously believe in their God-given mandate to witness to their respective faith (Qur’ān 5:48; Matt 28:19–20), it is therefore inconsistent—from the perspective of both faiths— to avoid witness in the name of dialogue. In my context, for example, when Christians and Muslims meet at ceremonies such as naming ceremonies and funerals, Muslims are usually the first to call Christians to embrace Islam. If they are so quick to do so without seeing it as offensive, it seems to me that inviting them to follow Christ (witness) in dialogue is both incarnational and reciprocal.

To illustrate this point, I recently was invited to participate at our local District Assembly (or town council). The imam was asked to open with prayer, and as a pastor I was supposed to close the meeting with prayer. After my prayer the imam felt the need to speak again but instead of praying he began to preach. His sermon was actually geared towards Christians in the gathering, evidenced by the fact that during his concluding remarks he said that Christians are trying to find God, but do not know the way to God. Since it was during Ramadan, he invited Christians to say the shahada and to accept Islam. As readers will determine, this particular setting was not necessarily meant as an occasion for either Christians or Muslims to share their faith. Yet the imam did not consider it offensive to invite Christians to Islam, and thus his call to accept the faith.

Perhaps Christians need to see dialogue and witness through the eye of the religious other, not in its content, but in its method: there need be no dichotomy between witness and dialogue. Indeed, the two are mutually inclusive. Christians and Muslims need to be engaged holistically by moving beyond understanding and appreciation of the religious other and proceed to questioning. It is only in questioning that genuine witness can take place. After all, if our dialogue partners do not separate dawa and dialogue, why should we?

Endnotes

1Cf. Volker Kuester, “Towards an Intercultural Theology: Paradigm Shifts in Missiology, Ecumenics, and Comparative Religion,” in Theology and the Religions: A Dialogue, ed. Viggo Mortensen (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 179.

2Ibid.

3This is a very common reality in sub-Saharan Africa. Cf. Lamin Sanneh, West African Christianity (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis: 1983), 221; and J. Osei Bonsu, ed., Ecclesia in Ghana: On the Church and Its Evangelising Mission in the Third Millennium, Intrumentum Laboris, First National Catholic Pastoral Congress (Accra: Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Ghana, 1997), 157.

4Cf. Notto R. Thelle, “Interreligious Dialogue: Theory and Experience,” in Theology and the Religions: a Dialogue, ed. Viggo Mortensen (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 130.

5John Azumah, “Issues in Christian-Muslim Relations and Their Implications for Theological Formation in Africa,” Journal of African Christian Thoughts 7, no. 2, ed. Gillian M. Bediako (Accra: Type Company Limited, 2004), 31.

6Kuester, “Towards an Intercultural Theology,” 179.

7Cf. Rahman Yakubu, “Christian-Muslim Relations in Ghana: A Reflection on the Documents of Christian Council of Ghana and Catholic Bishop’s Conference,” Master of Theology Thesis, Kampen University, The Netherlands, 2005, 75.