In October 2015, the International Center for Religion and Diplomacy (ICRD), Peace Catalyst International (PCI), and the Dialogue Institute (DI) convened a conference at Temple University designed to help Evangelicals and others understand the consequences of and develop thoughtful responses to Islamophobia in the United States. The conference had four main objectives: (1) to examine the present challenge of Islamophobia in America, with particular attention to how it relates to Evangelicals and Muslims; (2) to provide a biblical, historical, legal, and political rationale for greater tolerance across religions; (3) to develop (and lay the foundation for) a long-term strategy for Evangelicals and others to address Islamophobia in the United States; and (4) to develop tools for implementing that strategy.

To address the mistreatment of Christian minorities in Muslim-majority countries and that of American Muslims in the United States, the International Center for Religion and Diplomacy (ICRD) brought 19 Pakistani and American religious and civil society leaders together for a week in Nepal in January 2014, to establish an Interfaith Leadership Network (ILN). The purpose of this network was to build relationships between and among American and Pakistani interfaith leaders, and to design and pursue collaborative initiatives that would ease the plight of religious minorities in Pakistan, and counter the impact and spread of Islamophobia in the United States.

Toward this latter goal, ICRD engaged Peace Catalyst International (PCI) and the Dialogue Institute (DI) at Temple University as partners in convening a three-day conference to address Islamophobic sentiments within the conservative Evangelical community in America. The effort was underwritten by the William and Mary Greve Foundation and Halloran Philanthropies.

Background: the Rise of Islamophobia in America

The first clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America is fundamental to the effective functioning of our republic– “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” By Supreme Court interpretation, it has been applied to the individual states.

The Bill of Rights, which constitutes the first Ten Amendments to our Constitution, was ratified in 1791 and had been debated ever since it was first proposed in 1789. Today, it is under stress in a rather rare fashion, as significant religious figures argue that Islam has become inconsistent with American culture and law. This line of thinking is fanning the flames of what has come to be known as “Islamophobia,” a term which, when it was first introduced as a concept in 1991, was defined as an “unfounded hostility toward Muslims.” A significant number of Americans believe that Islam is so antithetical to our American way of life that they effectively dehumanize all practitioners of the Muslim faith as being irrational, intolerant, and violent.

The September 2001 attacks against the United States, which destroyed the World Trade Center in New York City and did enormous damage to the Pentagon, effectively triggered a campaign of fear-mongering against Muslims by influential commentators in the media and elsewhere. In reaction to this campaign and out of a recognition that the United States was unwittingly alienating the American Muslim community – perhaps its single greatest asset in combating Islamic extremists – ICRD co-sponsored a conference for U.S. government officials and American Muslim leaders in 2006 to address this problem. In partnership with the Institute for Islamic Thought and the Institute for Defense Analysis (the Pentagon’s leading think tank), ICRD convened 30 representatives from each side to determine how they could begin working together for the common good.

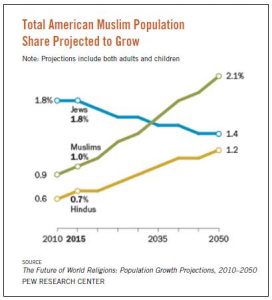

More specifically, the goals of the conference were first, to make the government aware of the legitimate grievances of its Muslim citizens and inspire the necessary action to address them. No one quite knows how large the American Muslim community really is, with estimates ranging from two to twelve million. What is known, though, is that American Muslims as a whole are well-educated, affluent, relatively young and politically active. Moreover, they have bought into the American dream. The second goal was to determine how the government could capitalize on the extensive paths of influence that American Muslims have with Muslim communities overseas and the last was to accommodate a Muslim perspective in the practice of U.S. foreign policy and public diplomacy.

The conference came up with a number of useful recommendations, and a second conference was convened a year later to monitor the progress toward implementation. As a result of this ongoing effort, the Muslim participants established a new organization called American Muslims for Constructive Engagement, which over a several year period joined ICRD in co-sponsoring a series of Policy Forums on Capitol Hill. The participants were key Congressional and Executive Branch staff involved in developing U.S. policies toward Muslim countries overseas, selected representatives from the American Muslim community, and relevant outside experts. The goal was to provide the Washington policy process with a more nuanced understanding of Islam; and from all indications, it helped to do exactly that. For the U.S. government’s part, the doors at the Departments of State, Defense, Justice, and Homeland Security opened wider to the inputs of its Muslim citizens.

Despite the success of such efforts, the Islamophobia campaign continued unabated. In a July 2010 address to a politically conservative audience at The American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC, for example, former speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich warned that the Islamic practice of sharia constituted “a mortal threat to the survival of freedom in the United States and in the world as we know it.” Such rhetoric can compromise the well-being of American Muslims and ultimately undermine their constitutional rights. Significant among those who have similar concerns are Evangelical pastors and their congregants who are often more negative than others in their pronouncements, hence the above conference at Temple University.

Contributing to the importance of such a conference was a study by a Washington-based think tank, the Center for American Progress (CAP), which put a spotlight on the problem in a 138-page report titled, “Fear, Inc.: Exposing the Islamophobia Network in America.” As the study shows, no fewer than seven conservative foundations collectively contributed over $42 million to exploit the fears and ignorance of Americans about Islam.

Recent trends suggest the effectiveness of this effort, with more Americans currently holding negative views of Islam than existed in the aftermath of 9-11. Also contributing to this trend is the fact that the media generally focuses on the violence committed by Islamic extremist groups rather than on the numerous Muslims who condemn this violence.

Temple Conference: Evangelicals, Islamophobia and Religious Freedom

The conference at Temple, which took place in October 2015, brought together some 30 prominent U.S. Evangelical leaders and selected representatives from the Muslim, Jewish, and non- Evangelical Christian traditions to address the various dimensions of Islamophobia, how they manifest themselves, and what can be done to counter them. The following articles authored by a number of the key participants capture the essence of these discussions, including a number of nuances that are commonly overlooked. What follows is a brief summary of the participants’ presentations and articles, all of which appear in this issue of the journal.

To provide a historical perspective, Howard Cohen, Adjunct Professor in Business Ethics at Temple University, explains how the nation’s founding documents protect its diverse religious practices and notes that it was the elevation of these protections into civil law that sets America apart. In this season when Islam is being scrutinized on the basis of extremist activities by ISIS and al-Qaeda, he said “we need to think scalpel, not meat cleaver. Our Constitution and Declaration of Independence require it. To refuse a more nuanced conversation about Islam in America rejects our unique values and the legal principles on which our nation was founded.”

With the above as backdrop, Imam Faisal Rauf, who chairs the Cordoba Initiative and who was previously identified with the Ground Zero Mosque, explained that the general hostility that many Muslims overseas feel toward America is almost solely a function of U.S. foreign policy and its heavy footprint in the Muslim world. Part and parcel of this footprint is the American support for authoritarian dictators that have prevailed for most of the last half century. The double standard of U.S. policy in the Middle East arising from its strategic relationship with Israel is also a factor. Finally, the collateral damage to Muslim civilians caused by U.S. military actions in fighting terrorism contributes to the hostility and ill-will as well.

Often unrecognized is the fact that Islamophobia has a far-reaching impact of its own that adversely affects American security and the safety and freedom of Christian minorities abroad. When Muslims in America are perceived to be mistreated, the situation for Christians living in Muslim-majority countries tends to deteriorate, as these Christians are often identified with the West, even if they have no direct connection.

Building on the above reality was a presentation by Dr. Elijah Brown, Chief of Staff of the 21st Century Wilberforce Initiative, who addressed the persecution that Christians often experience in Muslim-majority countries. Here, he distinguished between two categories of mistreatment, active persecution and structural discrimination. The former, he noted, is largely responsible for the fact that the Christian population in the Middle East has suffered a reduction from 15% of the total population in 1900 to less than five percent today.

More difficult to measure are the effects of structural discrimination, which are expressed in restrictive policies and practices, such as the misapplication of blasphemy laws in Muslim-majority countries (like Pakistan). One also finds examples of passive discrimination in national education systems, in which the existence and contributions of religious minorities are purposely excluded.

It is highly doubtful that the above consequences of Islamophobia are fully recognized by those who are contributing to its perpetuation. Exploring this aspect of the problem, Dr. David Belt, Chair of the Department of Regional Issues at the National Intelligence University, explains how proponents of Islamophobia have connected the external threat of Islamic extremism to an internal threat posed by Islamization, with the latter most often identified with a creeping institutionalization of Sharia Law that they claim will ultimately topple the United States. He also shows how the social conservatives who support this line of thinking have gone to great lengths in their cultural war with the progressives to link Islamophobia with the domestic Left.

For Evangelicals, there is an even more onerous correlation that is often drawn between Islam and the Anti-Christ, in which Mohammed is depicted as the false prophet of revelation. Further, their understanding of end times scripture leads to a strong pro-Israel bias to the point where they either “support Israel or be counted as God’s enemy.” As Dr. David Johnston, Visiting Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, goes on to explain, though, despite the seemingly irreconcilable doctrinal differences, Christianity and Islam share a number of common ideals that are good for society and suggests that this common ground is much wider than many might think, ranging from family values to peace to justice to serving the poor.

With the problem understood and its origins defined, the next question is what to do about it. Here Rick Love, President and founder of Peace Catalyst International, notes the double standard implicit in Christians who complain about the persecution of their brethren overseas, while turning a blind eye to the Islamophobia at home. As he puts it, “religious freedom for me, but not for thee.” He goes on to explain the Biblical mandate for religious freedom of choice, stemming from the concept of free will, the Golden Rule, and the admonition to love your neighbor. After explaining the benefits of religious liberty, he suggests that “religious liberty for all” should become a manifesto for Evangelicals.

Joseph Montville, Director of the Program on Healing Historical Memory at George Mason University, expands the scope for cooperation even further as he comments on the moral values that exist across all three Abrahamic faiths, e.g. the empathetic justice of Judaism, the spirit of forgiveness that constitutes the centerpiece of Christian identity, and the “natural religiousness” of Islamic faith. From there, he makes the case that because the core ethics of these faiths are essentially the same, i.e. liberty, equality, fraternity, and social justice, members of each of these faiths should feel a common moral responsibility for all.

Catherine Osborn, Director of Shoulder to Shoulder, builds upon these themes by describing how her organization, facilitates inter-religious collaboration in combating anti-Muslim bigotry. She notes that the anti-Muslim rhetoric of Islamophobia tends to disregard the impact that it has on the American Muslim community. As she elegantly puts it, “we work for the rights and inclusion of Muslims in American society not in spite of our own faiths, but because of them.”

Finally, Rev. David McAllister-Wilson, President of Wesley Seminary, challenges Evangelicals to take the lead in Christian engagement with Islam. He suggests that they are the most able to understand the experience of being Muslim in America simply because other Christians speak as disparagingly about them as they do about Muslims. Further, Evangelicals and devout Muslims are likely to be politically allied on a range of conservative social issues.

Finally, Rev. David McAllister-Wilson, President of Wesley Seminary, challenges Evangelicals to take the lead in Christian engagement with Islam. He suggests that they are the most able to understand the experience of being Muslim in America simply because other Christians speak as disparagingly about them as they do about Muslims. Further, Evangelicals and devout Muslims are likely to be politically allied on a range of conservative social issues.

Rev. McAllister-Wilson also notes that there is a natural desire for harmony and unity at the outset of inter-faith engagements, in which differences are often glossed over, but suggests that a richer and perhaps more meaningful approach would involve moving to a next phase that sounds “like the development of jazz in America, with its dynamic balance arising from dissonance and syncopation, creating surprising moments of harmony, and that resolve in a vibrant interfaith village.”

Majid Alsayegh, Chairman of the Dialogue Institute and a Muslim American born in Mosul, Iraq, closed the conference with a prayer in Arabic and English after first making an important point, i.e. that the American Muslim community is making a concerted effort to promote mutual respect between Christians and Muslims by stressing to its members the need to internalize America’s principles of religious freedom and equality for all and by being the first to condemn any violence done in the name of Islam.

Conclusion

The Japanese internment camps during WWII provide a stark reminder of how fear often drives us in directions we later come to regret. If we are not careful, current attitudes in some circles toward American Muslims could drive us in that same direction.

As we have seen from the foregoing presentations, the factors is the concern for persecuted Christians in Muslim countries, an aversion to the brutal excess of ISIS and other Jihadist groups, and the provocative role played by social conservatives in fanning the flames of confrontation. It is important, however, to distinguish between American Muslims and the Islamic extremists overseas. From a strategic point of view, American Muslims constitute one of our more formidable assets in the global war against militant Islam. Not only have they been instrumental in uncovering a significant number of al-Qaeda plots against the United States, but they also enjoy extensive influence with Muslim communities overseas – many in places of strategic consequence to the United States – that could be usefully engaged to good advantage.

Every bit as important as the above is the fact that American Muslims represent a beacon of hope to countless Muslims around the world, who are not disposed toward violence. They are mindful that American Muslims enjoy greater freedom of thought than Muslims elsewhere and that they actively bridge modernity and the contemporary practice of Islam on a daily basis, a feat that remains a puzzle for most other practitioners of the faith.

Ever since the fateful attacks of 9-11, one has heard the seemingly endless refrain of “Where are the moderates? Why don’t they speak out?” In some cases, the perceived silence is driven by fear – directly on the part of those living in areas that are actively under attack and indirectly on the part of those living elsewhere, but who have relatives in those same areas who could be vulnerable to retribution from the extremists. A competing reason for the silence, though, is the fact that when mainstream Muslims speak out, as many of them do, it is not deemed sufficiently newsworthy to warrant coverage in the media. Thus, the fact that more than a thousand American imams have issued fatwas condemning terrorism goes all-but-totally unnoticed, except when the community pays to advertise the fact in newspapers or other media outlets.

An even more telling reality, however, is the fact that the so-called moderates (or mainstream Muslims), have little, if any, traction with the extremists. Rather it is the conservative, non-violent Muslims who do and who should command most of our attention.

This still leaves one with the question of what should be done about Islamophobia? Perhaps the best clue is offered by Pew research polls, which show twice as favorable an attitude toward Islam on the part of those who actually know a Muslim than among those who do not. This, in turn, raises the further question of how to facilitate greater interaction between American Muslims and other U.S. citizens?

For Christians or Jews one option is to ask your pastor, priest, or rabbi to seek out the imam of the nearest mosque and begin a personal relationship. If that proves successful, then the next logical step is for the church or temple and mosque to sponsor a mixed social function for their respective congregations. Assuming that goes well, then the final step often takes the form of the pastor or rabbi preaching a sermon in the mosque and the imam doing the same in the church or synagogue. By the same token, Muslims should also encourage their imams to reach out, rather than waiting for others to take the first step.

The different ways in which we can come together as fellow citizens is limited solely by our imaginations. The time has come for us to step up to the plate and start imagining!