Danish filmmaker Andreas Koefoed, director and producer of The Lost Leonardo, truly believes that real life actually is in fact “stranger than fiction,” because the closer you look at any given story, the more layers of meaning, interest, and intrigue come to light. For this to happen, it only takes a healthy curiosity and the time and energy to start digging.

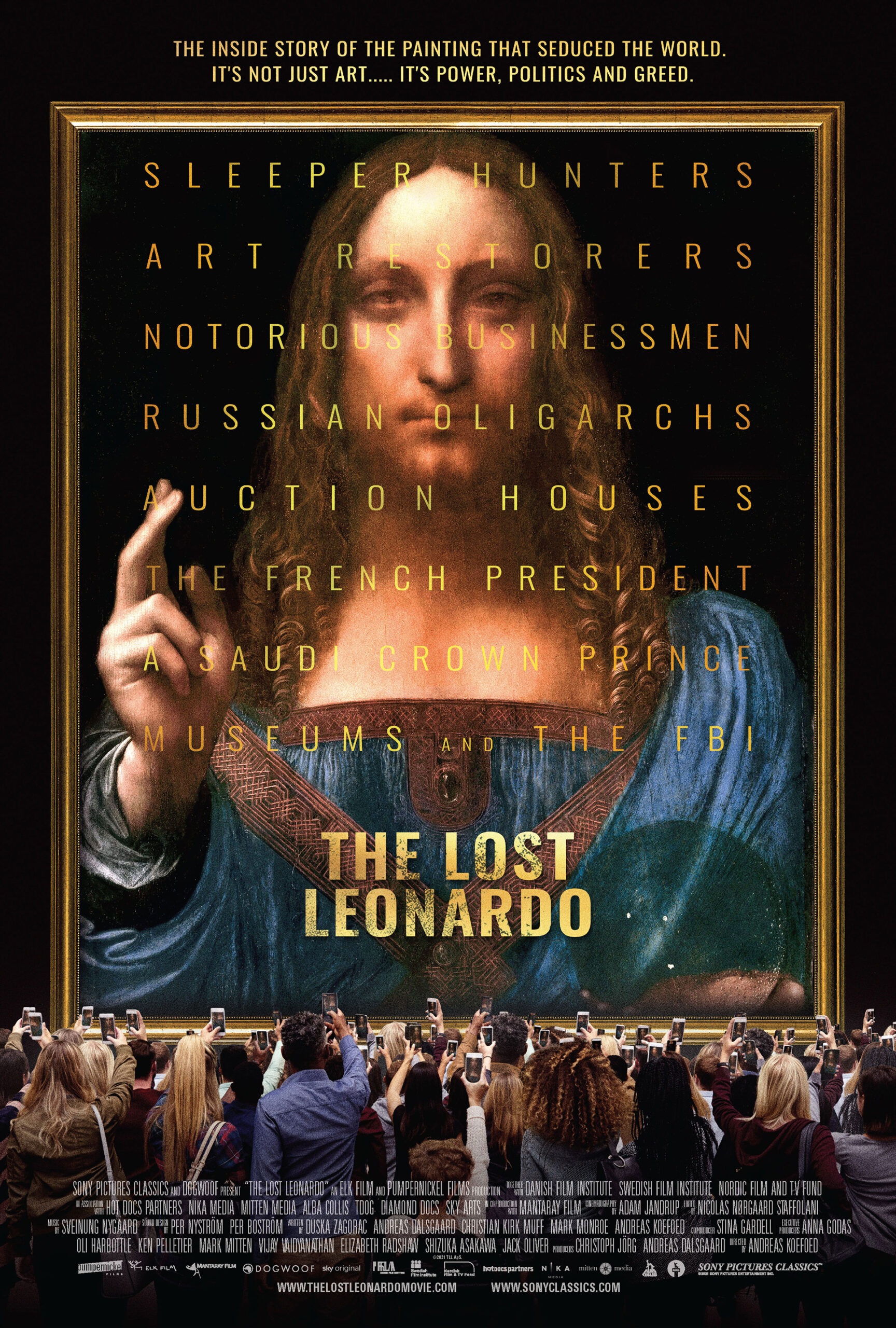

For Koefoed, the quest for the true story behind a painting known as the “Salvador Mundi,” which may or may not be a recently discovered original Leonardo DaVinci painting (marketed as “The Male Mona Lisa”), involves questions about the nature of value, truth in art, group−think, institutional and international power, history, and the nature of civilization itself.

The driving story thread in the documentary takes on a rags−to−riches plotline, the central theme being whether or not the painting, damaged and cracked, fished out of an estate sale in New Orleans in the year 2005 and sold for an inauspicious $1100, might actually deserve to be on display in the Louvre right next to the Mona Lisa as a work of greatness “from the hand of the master,” and of course, worth millions upon millions of dollars. Through the twists and turns of the story, you’ll doubt that a work of such importance could possibly have remained hidden all these years and then begin to believe that maybe this truly is a diamond in the rough. But by the second half of the movie, you’ll find yourself thinking more about the relationship of art to money and power, as the question of authenticity fades to the background and we are presented with developments that involve massive sums of money, Russian Oligarchs and Middle Eastern Royalty, and the geopolitical game of international power and prestige.

Watching the movie I was reminded of a concept introduced by cultural critic Thomas De Zengotita in his cultural communications book, Mediated. Whenever something of value, either in an aesthetic or creative sense, enters into the world, there is a kind of machine, which he calls “The Blob,” which seeks to exploit that value for some other purpose, be it political, personal or reputational. Often times, it’s the little people, who, in their naiveté, think that the world can accept the gift in love and harmony, but instead end up being crushed, in a sense, under the wheels of that great machine.

This is nicely illustrated in the film by the stark contrast between power−brokers in the art world who are dealing with Russian strong men, along with the fabulous wealth and power−politics of Saudi Royalty, and the simple pleasure of “the little people,” a self−proclaimed “sleeper hunter,” Alexander Parish, who found the painting at the estate sale, and Dianne Modestini, who painstakingly restored the painting from its dilapidated state. Once The Blob gets involved with the destiny of the enigmatic “Salvador Mondi” however, it matters little whether or not this piece of wood and paint was touched by the hand of the master, as it has become a pawn on the chess board of international power.

Danish filmmaker Andreas Koefoed, director and producer of The Lost Leonardo, truly believes that real life actually is in fact “stranger than fiction,” because the closer you look at any given story, the more layers of meaning, interest, and intrigue come to light. For this to happen, it only takes a healthy curiosity and the time and energy to start digging.

For Koefoed, the quest for the true story behind a painting known as the “Salvador Mundi,” which may or may not be a recently discovered original Leonardo DaVinci painting (marketed as “The Male Mona Lisa”), involves questions about the nature of value, truth in art, group−think, institutional and international power, history, and the nature of civilization itself.

The driving story thread in the documentary takes on a rags−to−riches plotline, the central theme being whether or not the painting, damaged and cracked, fished out of an estate sale in New Orleans in the year 2005 and sold for an inauspicious $1100, might actually deserve to be on display in the Louvre right next to the Mona Lisa as a work of greatness “from the hand of the master,” and of course, worth millions upon millions of dollars. Through the twists and turns of the story, you’ll doubt that a work of such importance could possibly have remained hidden all these years and then begin to believe that maybe this truly is a diamond in the rough. But by the second half of the movie, you’ll find yourself thinking more about the relationship of art to money and power, as the question of authenticity fades to the background and we are presented with developments that involve massive sums of money, Russian Oligarchs and Middle Eastern Royalty, and the geopolitical game of international power and prestige.

Watching the movie I was reminded of a concept introduced by cultural critic Thomas De Zengotita in his cultural communications book, Mediated. Whenever something of value, either in an aesthetic or creative sense, enters into the world, there is a kind of machine, which he calls “The Blob,” which seeks to exploit that value for some other purpose, be it political, personal or reputational. Often times, it’s the little people, who, in their naiveté, think that the world can accept the gift in love and harmony, but instead end up being crushed, in a sense, under the wheels of that great machine.

This is nicely illustrated in the film by the stark contrast between power−brokers in the art world who are dealing with Russian strong men, along with the fabulous wealth and power−politics of Saudi Royalty, and the simple pleasure of “the little people,” a self−proclaimed “sleeper hunter,” Alexander Parish, who found the painting at the estate sale, and Dianne Modestini, who painstakingly restored the painting from its dilapidated state. Once The Blob gets involved with the destiny of the enigmatic “Salvador Mondi” however, it matters little whether or not this piece of wood and paint was touched by the hand of the master, as it has become a pawn on the chess board of international power.

Justin Wells is a documentary filmmaker and author. Find more of his work at justinwellsfilms.com.

In How to Film Truth, Justin Wells explores the history of documentary filmmaking as a search for truth by filmmakers, and a journey of discovery for subjects and audiences.