An Augustinian Response and Contribution

In his essay, Kärkkäinen provides us with a concise introduction to the basic language, categories, and principles of interfaith dialogue. In addition to providing an argument for interfaith dialogue, he helpfully provides us with a theological foundation on which the discussion can take place. In this essay, I would like to take the conversation further by looking at interfaith dialogue from a different perspective. Kärkkäinen delineated the “what” and “why” of interfaith dialogue; I would like to explore the “how.” In particular, I would like to explore the “how” from an Augustinian perspective, considering the role the Church and its worship might have in interfaith dialogue. Augustine is hardly ever evoked in interfaith dialogue, but a close, creative reading of him can actually afford fecund resources for engaging in it.

Augustine believed that human beings are fundamentally lovers. They are always loving and being oriented by the things that they love; God created them this way. The opening lines of his Confessions highlight this: “You have made us for yourself and our hearts are restless until they find rest in you.” (1.1). Because God created human beings in this way, Augustine argued, their whole life should thus be understood within the framework of love. What human beings pursue and attempt to acquire should be understood in light of the object of their love (First Letter of John, 5.7-8). Thus, the believer should be understood and assessed by her love for God and the unbeliever by her love for herself. Indeed, there are two “kinds of love” (On Genesis, 11.15) and both of these loves lead to different courses of action. In turn, these two courses of action lead to two different ways of being in the world, or “cities,” as Augustine called them: the “city of God” and the “city of man.”

Like his understanding of the human person, Augustine’s understanding of the church was very dynamic and robust. He believed that the church participates in salvation and has a role in forming the love of its members. This led him to refer to the church as the mater fidelium, the mother of believers. What he meant by this is that God the Father uses the church to nurture believers in salvation, like a mother nurtures her child (Sermons, 216.7.7). God does this through its worship. here the church is gathered in love for Christ, worshipping him in the power of the Spirit, God’s eschatological reign is present, transforming believers and their love. He refines their love with his own (City of God, 10.3.2). Two important concepts are implied here that are worth noting. First, to truly know and assess a human being and her actions, one must consider what she loves. Second, while she is known and assessed by what she loves, if she is a Christian, her love is formed and transformed by God, the object of her love, through her worship of him.

For many of us, interfaith dialogue is primarily viewed as a rational tussle. We are oriented by the desire to demonstrate our beliefs. We think that by demonstrating how our beliefs are consistent, we show how they are true, and conversely, by demonstrating how our interlocutor’s beliefs are inconsistent, we show how they are false. But the focus here is solely on the logic of beliefs. While this logical tussle is indispensable, I wonder if it misses something necessary for any real dialogue. What if Augustine is right and we are fundamentally lovers? What if who we are and what we do is intimately linked with our love and its object of worship? Can we really be understood and our faith assessed apart from this worship? Conversely, can we really understand and assess the faith of another apart from their worship? What if to truly understand another faith not only requires us to examine its beliefs. but to observe or, even more disturbingly, experience its worship?1

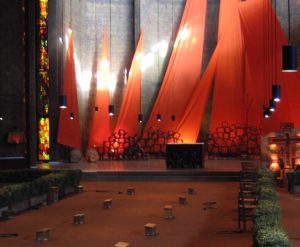

If the church of Jesus Christ is a sign of the “coming rule of God,” as Kärkkäinen rightly notes, then we should always be mindful that it is a witness to the truthfulness of God’s self-disclosure and claim on reality in the person and work of Jesus Christ. We often forget that the church is a work of God. The triune God is the creator and redeemer of all things, and the church is a testimony to this. Similarly, we often forget that God meets us in our worship. The triune God is eschatologically present in our midst, through our worship, and he himself testifies to his reality. We know he is real because he comes to us and we experience him. If indeed this is the case, shouldn’t we invite others to church in order to experience his presence? Shouldn’t we invite them to taste and see that he is good (Psalm 34:8)? While it may be terrifyingly uncomfortable, perhaps sometimes interfaith dialogue is more properly carried out by singing hymns in a sanctuary, listening to the Torah read in the synagogue, or praying at the mosque than sitting at Starbucks arguing over the problem of evil. Not that the latter is insignificant, only that from an Augustinian perspective, it is merely one part of understanding and assessing faith.

If our worship reveals who we truly are, perhaps it’s time for us to invite our interfaith interlocutors to church to see us as we truly are and, even more importantly, experience God’s presence in our fellowship and worship. Conversely, perhaps it’s time for us to attend their worship. This does not mean that interfaith dialogue should be ecclesio-centric—only that it should be ecclesio-considerate. As evangelicals, this should hardly be strange for us. For if we believe that our faith is a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, then some aspect of our dialogue should include the opportunity for our interlocutor to experience this relationship in and through our worship, where our savior promises to meet us (Matthew 18:20). If true dialogue entails “patient and painstaking investigation of real differences and similarities,” as Kärkkäinen rightly notes, then an Augustinian contribution to interfaith dialogue emphasizes that an investigation of real differences and similarities warrants at least some reference to worship, where all of us are authentically ourselves and the object of our love is manifested.

Endnote

1Experience does not necessarily imply participation. There is a passive and active aspect to experience. Here, I am primarily suggesting the passive aspect. That is, more of a spectation than a participation. That being said, however, participation should not be disregarded. Of course, there may be some observances and practices of worship that the Christian should not engage in and, in fact, boldly reject. But a wholesale abstinence from and rejection of all observances and practices of worship is hardly justified.