In his book Ritual in Early Modern Europe, Edward Muir describes the shift that took place with the invention of the printing press and its effects on the Protestant churches that arose out of the Reformation. Muir describes a division between the lower body, with the passions and feelings it contains, and the intellect and objectivity of the upper body, privileging the upper over the lower. For most Protestant churches this resulted in word-centered worship services, with most actions in worship involving speaking or singing—if not listening to—words. Since then, Protestants of all stripes have expanded their worship repertoire but in some ways still privilege words above all else. Yet we enter worship as embodied creatures. How does this fact shape our experience and understanding of worship?

My students, colleagues, and I study the psychology of worship. One of the questions we pursue psychologically is this: “What factors contribute to spiritual transformation in worship?” Several mechanisms have been used to explain emotional responses to music from a psychological perspective, including cognitive appraisal, rhythmic entrainment,1 visual imagery, and emotional contagion. In our first psychophysiological study of worship,2 we hypothesized that emotion would be associated with transformational experiences for parishioners. While emotion played a role, our participants also noted the role of cognitive dimensions. People identified key cognitive insights that were important for this process of transformation.

Although those results pointed to unity of upper and lower body in our experience of worship, they raised further questions. During praise and worship in corporate worship services, there are moments that many parishioners experience as powerful, anointed, and convicting. What facilitates these experiences? Does the worship song leader’s spiritual, emotional, cognitive, and bodily engagement influence parishioners’ spiritual experience in these moments? There are worship song leaders whose ministry leadership reflects a life in God. This is related not only to a sense of God’s presence in the moment, but also to a sense of their connection to and journey with God as it pertains to the song they are ministering. The next step in our research sought to explore the concept of embodiment as one way of understanding this multidimensional process of engagement and exploring God’s incarnational presence.

PERSPECTIVES ON WORSHIP

H. Wayne Johnson emphasizes the importance of a revelatory focus in corporate worship. He referred to this focus as the “deep structure of worship” and outlined four key dimensions:

We see the priority and precedence of God’s self revelation and redemptive work. We see the need for God’s people to attend and remember that revelation. We see that it is God’s character and redemptive work that elicit worship. Finally, we see that love and obedience are appropriate responses to God’s character and actions.3

The focus of worship needs to center on who God is and what God has done. The attention of people should be directed toward God and his presence rather than the personality, charisma, or even musical skill of the worship leader. The response to worship should include a deepened obedience to and love of God.

Debra Dean Murphy highlights the complex cognitive, emotional, bodily, and spiritual process involved in worship as she notes the following:

The “knowledge” imparted in worship . . . is a knowledge that can be known only in the doing of it. It is, at heart, bodily and performative. We are habituated to and in the knowledge of the Christian faith by the ritual performance that is worship, so that a deep unity between doctrine and practice is taken for granted.4

Worship is not simply cognitive; rather, it is a performative religious process that includes our hearts, minds, and bodies. Ritual fosters this deep unity between doctrinal beliefs and embodied practice. Worship, in other words, is seen as the actions and experiences of the entire person.

PERSPECTIVES ON EMBODIMENT

One of the most universal embodied modes of worship is singing. Embracing a broad perspective on the role of embodiment in music, John Blacking notes that “music is a synthesis of cognitive processes which are present in culture and in the human body: the forms it takes, and the effects it has on people, are generated by the social experiences of human bodies in different cultural environments.”5 This perspective underscores the importance of not only an integrated bodily and cognitive process, but also the cultural context. Noteworthy here is both the universality of embodiment—that every culture’s music assumes embodiment—and its particularity: that every culture understands, values, and executes embodiment somewhat differently.

Yet embodiment has even further levels of complexity, as again illustrated through music and described by Leslie Dunn and Nancy Jones:

We thereby recognize the roles played by (1) the person or people producing the sound, (2) the person or people hearing the produced sound, and (3) the acoustical and social contexts in which production and hearing occur. The “meaning” of any vocal sound, then, must be understood as co-constituted by performative as well as semantic/structural features.6

They argue that vocal meaning arises from “an intersubjective acoustic space” and any effort to articulate it must include a reconstruction of this context. Understanding musical expression in worship would therefore include understanding the producers of the sound, the listeners, and their social context. For worship leadership, this would include the song leader and his or her process of preparation: the social and, specifically, spiritual context of song production. Patrik Juslin describes these qualities as going beyond the performance and considering “the nature of the person behind the performance.”7

Music perception is associated with embodied movements—e.g., breathing and rhythmic gaits.8 Patrick Shove and Bruno Repp have noted, for example, that “the listener does not merely hear the sound of a galloping horse or bowing violinist; rather, the listener hears a horse galloping and a violinist bowing.”9 Further, recent neurophysiological studies emphasize the role of body motion in music production and performance. Such movement would be easily perceived in response to music such as jazz or contemporary Black gospel music, but it is perceived as well in music that evokes less perceptible bodily movements. Perceived rhythm is viewed as an imagined movement even in the absence of musculoskeletal movement. Consequently, says Raymond Gibbs, “musical perception involves an understanding of bodily motion—that is, a kind of empathetic embodied cognition.”10 Even something we do so regularly as listening to music opens into a multilayered embodied experience each time we do it.

Cognitive and social psychology are making important contributions to our understanding of embodiment.11 Gibbs defines embodiment in the context of the field of cognitive science as “understanding the role of an agent’s own body in its everyday, situated cognition.”12 Paula Niedenthal and her colleagues describe the embodiment process in body-based (peripheral) and modality-based (central) terms.13 They offer the example of empathy: based on understanding another person’s emotional state, people are able to recreate this person’s feelings in themselves.

Margaret Wilson differentiates “online” and “offline” embodiment,14 and Paula Niedenthal and her associates elaborate this further:

The term “online embodiment,” and the related term, “situated cognition,” refer to the idea that much cognitive activity operates directly on real world environments. . . . The term “offline embodiment” refers to the idea that when cognitive activity is decoupled from the real world environment, cognitive operations continue to be supported by processing in modality-specific systems and bodily states. Just thinking about an object produces embodied states as if the object were actually there.15

IMPLICATIONS FOR WORSHIP

Applying this categorization of embodiment to worship, the worship leader then must have an online experience of embodiment with their music. This might be a preparation process during which the song leader spends intentional time with the Lord meditating on the biblical meaning of the song. The worship leader would engage with the material and apply it to her life and social context. During worship, the song leader would seek to recreate an experiential space that connects with the song. Throughout the process, offline embodiment helps prepare the worship leader to minister and aids the process. There may be additional features of online embodiment. With the help of the Holy Spirit, the song leader recreates the experience in her mind and body and also creates anew in partnership with the congregation. Online and offline embodiment both occur.

A traditional view of preaching, expressed by Karl Barth, is that the preacher is a herald who speaks God’s words. The personality and preacher’s relationship to the words are unimportant. In contrast, Ruthanna Hooke argues that revelation does not occur in this way.16 She notes that “the voice of God does not come to us in a way that is removed from our historical, embodied existence. . . . In Jesus Christ, God reveals Godself not by bypassing humanity but by inhabiting humanity, the particular historical and embodied humanity of Jesus Christ. . . . God is most revealed in preaching not when the preacher strives to become invisible, but rather when she is most present in her particular, embodied humanity, in the room, meeting the text.”17

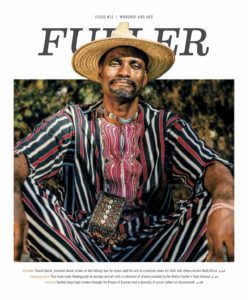

Worship leaders who more fully and synchronously embody the depth of their spiritual engagement may contribute more powerfully to their own and others’ spiritual transformation through the work of the Holy Spirit. In order to identify key processes that might contribute to a worship leader’s spiritual engagement and embodiment, we interviewed 26 music worship leader exemplars from various ethnic and denominational backgrounds.18 Primary areas of inquiry included Christian formation; the roles of embodiment, cognition, affect, and spirituality in worship; leader preparation; and the congregation’s role.

The most prominent themes that emerged from these interviews were bodily signals, God’s action and presence, God-centric engagement, facilitating worship, divine purpose, and continual commitment to spiritual formation. God-centric engagement referred to the worship leaders’ focus on glorifying God in their worship. In addition, attunement to the deep structure of worship was also evident as worship leaders expressed their desire for communion with God and made regular reference to Scripture.19 They noted actions in their body that reflected this attunement. Their prayers focused on yielding to and being led by the Holy Spirit. Their intent was to direct attention toward God rather than using themselves to draw people. They also described a 24/7 commitment to preparation, viewing spiritual preparedness for worship as an ongoing orientation and desire in daily life to be more yielded to God.

This description by worship leaders reveals how their preparation facilitates their ability to be attuned to God as they lead worship. In a similar way, our engagement with God through Scripture reading, prayer, and fellowship reflects online embodiment that enhances our ability to be more Christ-like in our daily interactions. Our encounter with God’s grace through Scripture and our sense of his great mercy toward us can evoke feelings of warmth and deep gratitude. The offline manifestation of this might arise as we encounter a situation where we can extend grace to others. We might feel a similar sense of warmth and gratitude in our body that we extend toward someone in our life. Remembering the countless examples in God’s word of his grace and mercy helps us not only to speak words that sound gracious, but also to reflect the grace of God in verbal and nonverbal ways: to be gracious.

This provides an invaluable reminder that, as Christians, our central desire should be a life that seeks to glorify God: that we would be students and followers of his Word and that the Holy Spirit would lead, guide, and empower us. The aim of worship is to glorify God, but as Don Saliers reminds us, this is culturally embodied and embedded: we bring our whole lives to worship.20 I am thankful that we serve a God who views us holistically and helps us in our desire to worship him in spirit and in truth.