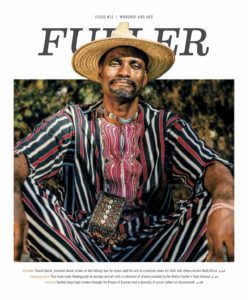

Daniel Dama is intensely committed to his mission: sharing the gospel across West Africa not just in words, but through the music he so deeply loves. “I want to save my people,” the Fuller PhD student says with passion—and, as a missionary with an organization called the Joint Christian Ministry, that means traveling throughout 15 countries, from Chad to Senegal, helping others know the joy he’s found in Christianity. It can be a tricky, often dangerous business, as just getting from place to place in a region that’s both arid and tropical, desert and jungle offers distinct challenges.

“Sometimes we have to book public transportation,” he says, “which means that in a small car meant for four people, they’ll put, like, 15. Sometimes the driver cannot even reach the pedals. Someone else—a passenger—has to press them. If the car breaks down, it will take four to five hours to get it fixed. If you’re on a bus, someone might give you a goat to hold. Sometimes we have to take a boat on a river, traveling hundreds of miles. Then, when we jump from the boat, we have to walk about 20 miles in the jungle. Sometimes you find poisonous snakes on the road. The mosquitoes are everywhere.”

“It’s very interesting,” he says with a smile, “to be a missionary in Africa.”

For this married father of four with a gracious, engaging personality, the path has been winding and littered with obstacles from his early days. Dama, as he is known to everyone, spent his childhood in Goro village in northern Benin, a small, close-knit community where his grandfather was chief. He is a member of the Fulani tribe, one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa, numbering upwards of 25 million people. Because of his paternal lineage as a “noble,” he was expected to eventually follow in his grandfather’s footsteps.

Dama, however, had other ideas. He wanted to become a musician—part of a different caste in his region’s social hierarchy. “That caste includes goldsmiths, praise singers, musicians, cobblers, weavers,” he explains. “All are culturally at the service of the nobles, which my family was. Given that I am not by cultural norm from that lineage, it was seen as a taboo that I become a singer. But God gave me talent, and I loved music!”

As a child in Goro, he witnessed many ceremonial events that drew praise singers or “griots”—traditional musicians and storytellers—from the region, and he was intrigued. “My interest was focused on these musicians and their performances,” Dama remembers. “I always followed them, sometimes late in the night, in order to capture the way they performed. Later, I imitated them clandestinely because I would be rebuked if a family member should see me sing like men from the wrong caste.”

Dama began composing his own indigenous songs, and experimented with making bamboo flutes and small, guitar-like instruments. None of this was good news to his family. “My mother rebuked me terribly, saying, ‘Don’t be a curse for our lineage and family!’ My uncles and aunts likewise menaced me. All of that intimidated me beyond description. As a result,” he confesses, “I abandoned making music and accompanying praise singers”— heartbreaking as that was for him.

His love for music wasn’t the only way the young Dama butted heads with his elders. Another point of contention was his first name: Daniel. After his birth, American missionaries in Goro village asked for permission to name the new baby boy—and, surprisingly, his grandfather granted it. Throughout his childhood, young Dama despised his name because it was so foreign and unusual. “I was very angry because I was the only boy with this name!” says Dama. “For years, I kept asking my grandfather to change my name, but he told me to keep it.”

His love for music wasn’t the only way the young Dama butted heads with his elders. Another point of contention was his first name: Daniel. After his birth, American missionaries in Goro village asked for permission to name the new baby boy—and, surprisingly, his grandfather granted it. Throughout his childhood, young Dama despised his name because it was so foreign and unusual. “I was very angry because I was the only boy with this name!” says Dama. “For years, I kept asking my grandfather to change my name, but he told me to keep it.”

Raised in the Islamic faith, Dama came to Christianity in his late teens, inspired by a man who’d been traveling to his village on a rickety old bicycle for 25 years sharing his Christian faith. Dama went on to earn a diploma in Theology and Religious Education from Baptist Theological Seminary in Nigeria, and—now feeling the freedom, away from home, to renew his interest in song—followed it with a bachelor’s degree in music. “Like Amos, I heard the call of God,” Dama recounts, “and I felt deep inside me that I had a message to take to my people via music.” He further equipped himself to do just that by coming to Fuller, in Pasadena, for an MA in Intercultural Studies—an experience that expanded his perspective.

“At Fuller, students from all nations filled the classrooms, and we learned from each other and shared experiences,” he says with enthusiasm. “We learned about the power of listening and how to talk with people of other faiths. People have stories to share and things to say, if we will only create space for them. I discovered that talking about art and culture can be one way to start conversations and find common ground.”

When he finished his master’s degree in 2014, Dama took that knowledge back to West Africa—and founded the Fulani Christian Festival of Art and Culture, a three-day event that’s been held every year since. As he talks about it, he opens a video on his phone of a previous year’s festival. Men, women, and children crowd together on the ground in a covered area, sitting row upon row, waving, swaying, and singing along with the music. Woven cloth and leather hats and other items sold by festival crafters adorn them. On stage, performers sing, drum, and strum songs of praise. Among them is the tall, commanding presence of Dama, who leads the music, sings, and often plays drums or the hoddu, a small stringed instrument.

He gleefully taps the small phone screen with his long, elegant fingers and points to the children sitting cross- legged on the floor in front. “Look at the children, look at them!” he says. “I love to see the children—so happy, so involved.”

About two thousand people came from all over West Africa for that first festival—“even non-Christians sent their youth and children,” he notes. This delights Dama, because this was his hope for the festival: that it would, in a region where young people are sometimes recruited by radical groups, draw them into a different kind of life. Though certainly not true of most Muslims, Dama says, “there are extremists who say to Fulani youth, ‘Fight the West—fight the infidels.’ But at the festival, we are teaching them not hate but love. Art and culture are a common ground for everyone.”

The Fulani festival has been so well received that Dama was asked by the Minister of Culture to be an official cultural advisor, helping to oversee similar events for a wide swath of West Africa. He turned down the offer, wanting to devote himself fully to the missionary work that leads him all over West Africa—whether that’s crammed in a car, carrying a goat on his lap, or dodging snakes in the road—connecting with those of other faiths and cultures through both word and song. He carries with him music CDs, cassettes, and hymnals on his journeys, giving them out with Bibles, recorded sermons, and literature, all in the Fulani language.

“My people are hungry for something, but they don’t know what,” Dama says, and it’s his mission to help feed that hunger with his faith. To his great joy, he now has support from his family, too. Dama’s parents both became Christians, as did many other relatives—the same people who couldn’t understand his call to be a praise singer so many years before. “Today, my mother, aunts, and uncles sing the songs and dance to the music I make for the glory of God, who endowed me with this exceptional gift,” says Dama with delight.

What’s more, Dama now sees that first name he was given as one of the many blessings of his life. “Today, I am still Daniel, and am profoundly grateful for the name I carry. Because, like him, I am a warrior, and my weapon is the word of God. My name was very prophetic!”