Sabbath rest is not simply the religious equivalent of a day off from work. The very notion of a day off is a negative one, suggesting the need to escape our brick-making for the sake of our sanity. If we have the means, we vacate, we get away, and then we return to the same job perhaps slightly better rested but with the same attitude. This is not Sabbath rest. We may enjoy leisure activities on the Sabbath, but Sabbath rest is not to be identified with leisure. It’s not simply an opportunity to get away from work, to do things to recharge our batteries, but to cultivate a right relationship to our work. It’s an opportunity to remember who we are: the beloved children of a God who blesses the poor in spirit, who feeds those who wander in the desert. We need to be secure in that identity in order to be rightly related to our work. Toward that end, Abraham Heschel insists that the Sabbath ‘is a day in which we abandon our plebeian pursuits and reclaim our authentic state, in which we may partake of a blessedness in which we are what we are, regardless of whether we are learned or not, of whether our career is a success or a failure. It is a day of independence of social conditions.’

As Christians we need more than just escape or distraction. More than just a day of vacation or binge watching on Netflix. Sabbath rest is not simply about forgetting work but about remembering who God is and who we are as a consequence. We need a regular discipline that will help us to remember that our worth is not defined by our work, that our value is not measured by our productivity.

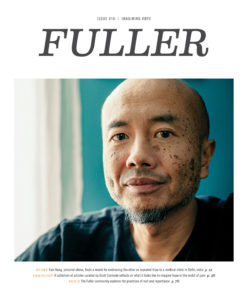

+ Cameron Lee, professor of marriage and family studies, in “FULLER dialogues: Therapy as Peacemaking,” originally

As ministry leaders, we do a good job of caring for others but often we do not extend the same care to ourselves. The work is challenging, and the seemingly endless demands of preaching, counseling, and visioning keep us busy. Perfectionism, productivity, and exhaustion can often become symbols of our dedication and the measure of our self-worth. And though we comfort ourselves with the belief that all this is necessary for the kingdom, we struggle with fatigue, anxiety, and discouragement. We grapple with the growing incongruity between how we present ourselves to others and what we may be experiencing on the inside.

A friend of mine charged with the care of pastors in the Evangelical Covenant Church shared a formula for unhealthy ministry: depletion + isolation + conflict = significant trouble. We know that conflicts and challenges in ministry are inevitable! But when conflict encounters a leader’s untended depletion and isolation, trouble is also inevitable. If we are not careful, busyness can kill us—emotionally, spiritually, relationally, and physically.

Perhaps it’s time to stop and reevaluate the rhythms of our work and rest. It goes without saying that we need to work hard, to be faithful and fruitful in our work. Still, a Sabbath lifestyle is fundamental: living and working out of a place of quietness before the Lord. In a culture that values speed and productivity, Jesus shows us another way. In the midst of busyness, he took Sabbath, stepped away, went to a solitary place, and prayed. When we choose this kind of Sabbath lifestyle, we are confessing that we want our identity to align with the radical and subversive example of Christ.

+ Kurt Fredrickson, associate dean for the Doctor of Ministry and continuing education and associate professor of pastoral ministry, in “Rhythms of Work and Rest for Ministry Leaders” on FULLER studio

When we are unable to stop or say no to the requests of others, we may be acting as rescuers rather than as coworkers with the one true Savior who redeems us for shalom. The messiah complex prevents us from realizing our own need for transformation, instead seeing transformation as something that needs to be accomplished ‘out there’ and not ‘in here.’ The principle of Sabbath is one way to regain perspective on our identity and role in our work. Sabbath means not only resting but ceasing, including ceasing to try to be God. On the Sabbath, ‘we do nothing to create our own way. We abstain from work, from our incessant need to produce and accomplish. . . . The result is that we can let God be God in our lives.’1 When we remember who God is in our lives, we are reminded of our role and God’s role; we can refrain from the temptation to be God in the lives of those for whom we feel responsible.

Sabbath creates a time and space in which shalom relationships are lived out and marred relationships are made whole. The accurate ‘I’ view of the self is deepened as we experience God in the keeping of the Sabbath and Sabbath rest. Exhaustion is not the mark of spirituality. Sabbath is not only about personal time with God, or a personal time of rest, but also the place in which social support can be encouraged. Sabbath is a communal event that is best and most fully shared with others. Once Sabbath thus alters our orientation, it is not so much an isolated day as an atmosphere, a climate in which we live all our days. Sabbath offers a foretaste of what is to come, when all will live in shalom.”

1 Marva Dawn, Keeping the Sabbath Wholly: Ceasing, Resting, Embracing, Feasting (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989).

+ Cynthia Eriksson, associate professor of psychology, Jude Tiersma Watson, associate professor of urban mission, and Ashley Wilkins (PhD ’16) in “Caring for Practitioners: Relationships, Burnout, and Sustainability” in FULLER magazine issue #5

Evil is pervasive and seemingly ever-present. How can humans avoid evil and find holiness when we are so fragile and full of sin? There are those who seek justice by keeping the law and showing their good deeds as a sign of holiness—salvation by works. The heart of the law, however, makes this evident: We pursue holiness when we take 24 hours every week for personal rest as an act of worship to God. Even from the time of the Old Testament, the key to holiness was not salvation by works but, instead, was made clear in a commandment to rest in God.

The fourth commandment demands that we include all family members in this rest, but it does not stop there. We are also required to seek out our neighbors, to embrace the employees under our care in this rest and, in addition, to be ecologically minded and include the natural world in this rest with God!

We must make it a priority in our lives to keep the Sabbath, and in so doing, to seek holiness through rest and restoration.

+ Johnny Ramírez-Johnson, professor of anthropology and profesor del Centro Latino, in “Sabbath as Model for Restoration” in FULLER magazine issue #6

I think I can do it all. But, nearly every day for the last six months, God has shown me that I simply cannot do all that I have promised I will do. My job at Fuller requires a lot. The company I own is busy and flourishing. My daughter is an energetic toddler. And as much as I’ve tried to just muscle through it all by forgoing my own rest, it hasn’t worked. I’ve dropped balls in my work, failed in moments with my kid, and disappointed people I care about. I’ve come face to face with the reality that, when it comes to doing it all, I am not enough.

In other words, I am coming to grips with my own humanity. God is making it clear that I am not enough to do all of these things—but also mercifully showing me that because God is the great I AM, I am enough to just be with God.

God is guiding me in my dysfunction—mostly toward rest and play. Having a kid makes the play part pretty doable. When I walk in the door to my kid’s room, I can’t help but be whisked away by her desires to make Play-Doh pizza or to play school with her stuffed animals. And I find that when I give myself over to her sense of whimsy, I am also being with God. Through play, I am able to sense that I am enough.

Rest is a little harder for me to submit myself to. But opportunities for small doses of quietness seem to keep presenting themselves. Rest is vulnerable in that I mostly have to be alone with myself and with God. I’ve been in such a pattern of doing that I fear I’ve forgotten how to fully be. But, each time I give over to rest, I find it a mode of resistance for the myth that I can and should do it all.

+ Michaela O’Donnell Long (PhD ’18), senior director of Fuller’s De Pree Center, in “Rest, Play, and the Costs of Believing”

The world says that if we do a certain thing, we will have peace—or identify in a certain way, we will have peace. And maybe we will, for a moment. Then there’s something else after that, and onward we go away from true peace—the peace that surpasses all understanding—never whole, never settled, propelled back into desperation and division. Reality becomes unmanageable and untenable even as we may hold onto words about Christ.

In contrast to the peace of the world or the narrowed peace offered by a religious demographic, the peace Christ gives us in the Spirit is a transforming peace. It is the Spirit who awakens our self-imagination. Someone who is free in the Spirit, who has peace in the renewing life of Jesus, ‘knows himself in his spiritual essence,’ as Anthony the Great once wrote, ‘for he who knows himself also knows the dispensations of his Creator, and what he does for his creatures.’ This knowledge is given by the Spirit, and as we participate with the Spirit, we are given discernment about ‘all things,’ even our own self. Sometimes this Spirit says go and sometimes this Spirit says stop, enabling a life-giving rhythm in our lives instead of exhaustion. The Spirit of holiness is also the Spirit of Sabbath. I’ve had to remind myself of this again and again.

+ Patrick Oden, visiting assistant professor of theology and church history, in “Passing the Peace: A Pneumatology of Shalom