“As the eyes of servants look to the hand of their master, as the eyes of a maid to the hand of her mistress, so our eyes look to the Lord our God, until he has mercy upon us.” –Psalm 123:2

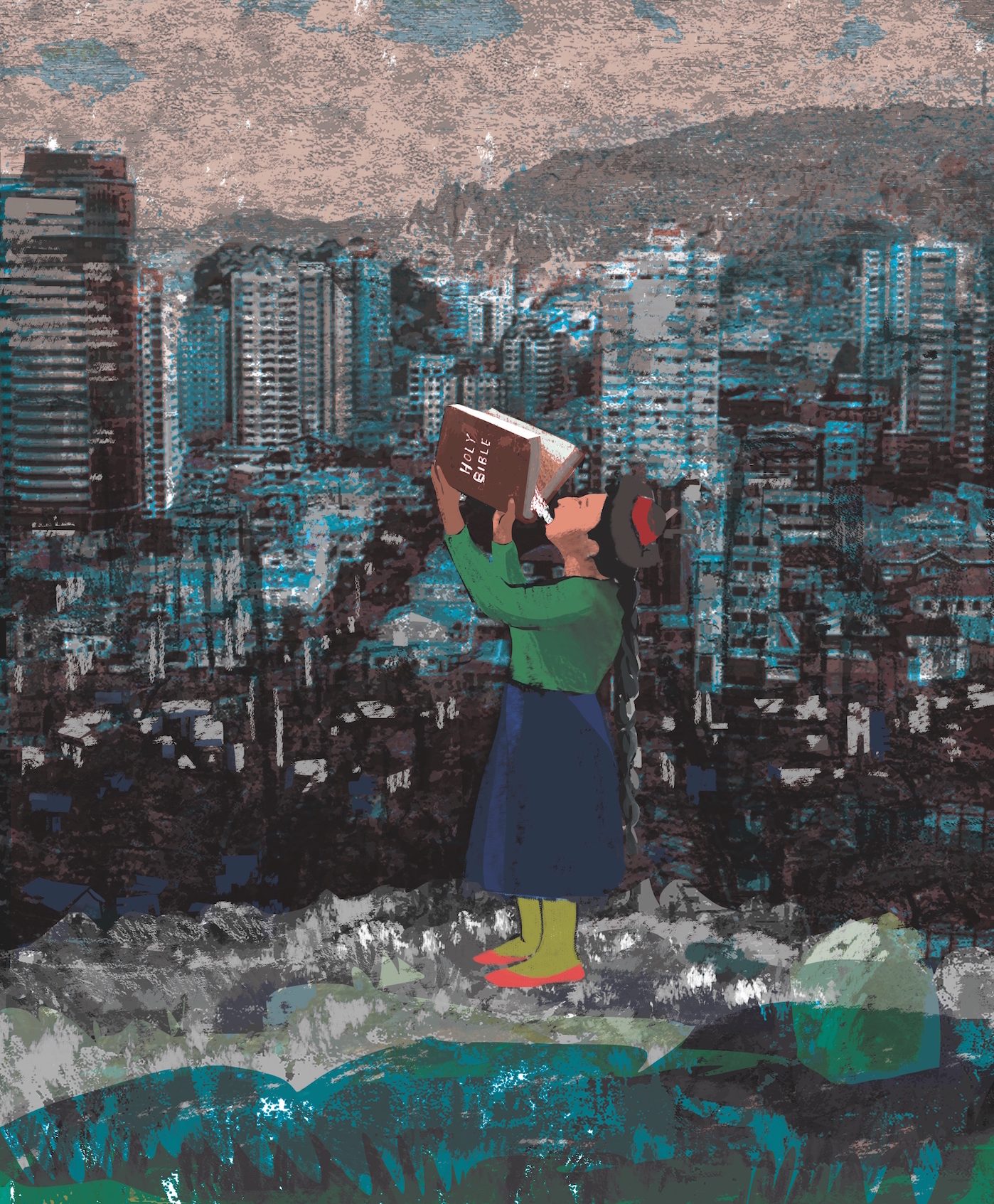

The explosion of Protestant evangelicalism in Latin America is a phenomenon largely accomplished by worshipers joining evangelical churches as adults. A report by the Pew Research Center in 2014 notes, “Just one-in-ten Latin Americans (9 percent) were raised in Protestant churches, but nearly one-in-five (19 percent) now describe themselves as Protestants.”1 Many of these people were not raised in church, nor taught the Bible as children. Like the many indigenous women in the Andes region who read the Bible fervently, often carrying it as the one book in their humble aguayo (colorful woolen carrying cloth), they are grassroots readers.

There is not much literature on how these women read the Bible or how it impacts their daily life, but close observers of Christianity in the Andes region can note profound transformational effects on how these mujeres indígenas and their local faith cultures navigate the daily challenges of life, especially the oppressions of gender, race, and class.2 This essay does not intend to fill a scholarly lacuna, but it seeks to provide examples of real, practical applications of hermeneutics on the ground and in the lives of local believers in the Andes region.

Having spent my formative years in a missionary household in La Paz, Bolivia, here I share the story of mis hermanas de la Iglesia Bethesda. The great majority of hermanos y hermanas (“brothers and sisters,” a common designation of congregants in Protestant churches) who read the Bible in the Latin American context view the Bible as a definite source of inspiration and authorization for the typically quotidian actions of daily life. Much like their fellow Christians in the United States, Latin American believers—and especially those among the rural and working class segments of society—relate to stories of human toil, struggle, and emotion, often personalizing sections of a biblical narrative that academic theological study might paint differently. Those who cannot count on the government or other institutions to resolve grievances and disputes, provide basic care for children, or alleviate fierce competition for limited resources tend to feel that they must desperately cling to God. Especially in these respects, the Old Testament speaks to and validates raw life experiences.

Biblical stories of hardship also speak to these believers in unique ways based on their different experiences of human nature and social conditions. These readers take notice when the biblical narrative depicts natural catastrophes, unpaid wages, or discrimination—experiences that more commonly and disproportionately affect minorities and the poor. Accordingly, reader responses to such narratives play a greater role in shaping faith culture where most believers are poor and underprivileged than in communities that enjoy basic security, property rights, material prosperity, and political self-determination. For believers in my parents’ community in La Paz, witnessing biblical protagonists face these familiar issues takes them beyond the place of the reader, making them participants in the Bible through the vital ethical and affective responses it stimulates.

I am wary of the temptation to exoticize the Bible reading of mis hermanas, but my formative years spent in La Paz suggest to me that narrative elements that are inert in some contexts come alive in others, often to powerful effect. To the indebted, ill, or downtrodden woman, a God who advocates debt forgiveness (e.g., Neh 5), provides miraculous healing (e.g., 2 Kings 4), and vanquishes those who deny justice to the innocent (e.g., Isa 5:23) becomes personal and close instead of abstract or far off. Identifying with a character in the story makes it easier for a reader to believe that the creating and redeeming God of the Bible knows her.

What is more, this depth of identification is often accompanied by a correspondingly higher degree of expectation placed upon God—or at least one that comes less self-consciously. The theologian Karl Barth, in a series of lectures delivered in 1949, reminded us that in prayer we are obliged to “meet [God] with a certain audacity: ‘Thou hast made us promises, thou hast commanded us to pray . . . and I say to thee what thou hast commanded me to say, ‘Help me in the necessities of my life.’ Thou must do so; I am here.’” 3 As scandalous as it might seem to some Western Christians, our hermanos and hermanas in South America expect and demand that God respond to them with urgency, and they have fewer qualms than we often do about issuing prayers that can sound to our sensitive ears like an injunction. Validation, comfort, and hope from a living God are unquestionably preached for life here and now, not in the distant abstract afterlife.

EXPERIENCING THE BIBLE IN BOLIVIA: INDIGENOUS EXEGESIS

Zona Rosales is a rural township located on the outskirts of the city of La Paz. In the 1980s, when my parents first moved our family to the area, the barren mountain hills of Rosales were considered clandestino and the district did not qualify for the city government’s development plan of urbanización. At the time, the area had no access to running water or electricity and was inhabited by extremely poor indigenous families. We founded the Bethesda School and Church in 1988 after constructing the first building out of bricks made from adobe mixed with clay and water hauled by local laborers. From this site, it took half an hour’s walk to reach the nearest public transportation. Families with six, seven, or more children were not uncommon, and the sight of school-age children playing in the dirt lanes during daytime hours was typical. Rosales families could afford neither school supplies nor the matriculation fee, which in those days was usually around the equivalent of one US dollar per child per year.

My parents had emigrated from South Korea to Bolivia three years earlier, and they decided to move into Tujsa-Cota (the original, indigenous name for today’s Rosales) in order to serve the local community more effectively. They believed that the good news of Christ’s salvific power combined with quality education would maximize every child’s potential and could release him or her from the brutal cycle of poverty and ignorance that had been the norm in this neighborhood and many like it in Bolivia. In its first academic year, the school enrolled 150 children aged 5 to 12, providing free education and inviting their families to join Sunday church services. As the school gradually expanded to K–12 education, it attracted a robust constituency from Rosales and other adjacent zonas and began producing graduates, most of whom were the first generation in their families to attain high-school diplomas. In recent years, more than 80 percent of graduates, about half of them young women, have gone on to universities and other comparable institutions of higher education. Today, the school has five buildings and a total enrollment of approximately 900 students. Most come from families who are now able to pay a nominal fee, having benefited from decades of economic growth as the neighborhood stabilized, was eventually annexed by the city, and began receiving water, electric, sewer, and other municipal government services.

Most of Bethesda’s congregants were originally nominal Catholics. Some had been baptized as infants, but most maintained no ties with any church. A significant percentage of adult congregants—the parents of the students—hailed from the distant campos, subsistence farms in the Bolivian altiplano hinterlands. They had left agricultural life behind and migrated to La Paz in hopes of benefiting from the comforts of life they expected to find in the city. Their mother tongue was Aymará or Quechua—languages spoken by the majority of the Andes people in the past—but now they spoke Spanish in everyday life. Marked by their accents and a limited vocabulary, they struggled to fit in with the urban culture. These landless migrants, disparagingly referred to by wealthier Paceños as campesinos because of their ethnic and cultural origin, now worked in whatever menial jobs they could find. Los hermanos at our church predominantly worked in construction, while las hermanas primarily washed laundry and cleaned houses in affluent sections of the city. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, we saw a number of congregants become embroiled in wage disputes and other forms of labor abuse with their employers. The absence of strong laws and enforcement to ensure human rights or protect against unemployment and labor abuse meant that such complaints were common.

A typical example was Hermana Celia, who had migrated from a rural village near Cochabamba. She, her husband, her mother-in-law, and her five children lived in a one-room structure, which served as their bedroom and kitchen. Their modest house belonged to a wealthy mining company executive. Hermana Celia and her family had been hired as cuidadores (guards at a property), and Hermana Celia’s husband also worked as a handyman at the executive’s house. For 13 years they received no salary payments, having been told that one day when Rosales was incorporated into urbanización, the executive would sign their plot’s lien over to Celia and her husband in lieu of back pay. Naturally, as soon as urbanización and the introduction of basic services materialized, the price of land in Rosales skyrocketed. The family lost their home and found themselves entangled in a legal dispute with a powerful adversary.

Needless to say, congregants like Hermana Celia were not versed in critical methodologies, sophisticated reading strategies, or hermeneutical perspectives. The experiences of their daily lives were the basis for interpretation and engagement with the Bible. In reading and attempting to live Scripture, they drew from wisdom and pragmatism acquired through struggles with the everyday hardships of poverty, prejudice, and injustice. Their social and material conditions were the primary factor that informed how they sought guidance from Scripture.

In accordance with this nuanced and pragmatic view of life conditions and human nature, readers like Hermana Celia were not too conflicted when encountering ambiguity in the Bible. Real life was fraught with ambiguities and gray areas, so they were less scandalized than their American counter- parts by the questionable choices and actions of the biblical characters, including God. Their choices, like some made by the biblical characters, did not necessarily square with a dogmatic framework. God’s ways could be discerned more clearly through uncertainty, with ambiguity often serving to prompt discernment and openness to the miraculous.

“During my daily reading of Scripture I might be disturbed or reminded or comforted or prodded, but no matter how the Spirit works with the text on any given day, I am living out my Wesleyan habit of giving these texts a primary place amidst all of the other words that surround me. In this way the habitus of my life, the maps that frame how I perceive and interpret and act, is shaped by biblical stories, poems, letters, and prophets.”

“During my daily reading of Scripture I might be disturbed or reminded or comforted or prodded, but no matter how the Spirit works with the text on any given day, I am living out my Wesleyan habit of giving these texts a primary place amidst all of the other words that surround me. In this way the habitus of my life, the maps that frame how I perceive and interpret and act, is shaped by biblical stories, poems, letters, and prophets.”

+ Mark Lau Branson is the Homer L. Goddard Professor of the Ministry of the Laity at Fuller Seminary. An ordained pastor, he teaches in the areas of congregational leader- ship and community engagement.

Based on my own observations of situations like Hermana Celia’s, I note two principal ways in which reading the Bible uniquely impacted the lives of Bible readers—and especially of indigenous women readers—at Bethesda. Although these patterns may not show up in all developing-world Christian communities, I believe these dynamics can likely be seen in similar populations around the world.

First, Bible reading itself often became the means to secure a basic level of personal autonomy and self-determination that is nearly universal in the United States, but is not as widespread among Bolivia’s indigenous poor. The Bible was a gateway to literacy and, hence, personal dignity and empowerment. Literacy levels among our congregants varied widely: a typical hermana at our church in the late 1980s probably read at a third grade level, and some were completely illiterate. Most had not finished elementary school. Protestant churches in Latin America tend to emphasize individual Bible reading, but many of our hermanas had never read a book cover to cover before. Once they identified themselves as cristianas evangélicas, they started reading the Bible voraciously, participating in Bible study groups and other community learning activities as a means of solidifying not only their faith, but also their reading ability.4

Second, in reading and responding to the Scriptures, our hermanas were not necessarily influenced by a gender-driven interpretive frame. The Bible had opened their eyes to their inherent value and dignity as humans, and their core identity did not reside solely in gender. Of course, many of the challenges these women faced existed because of their gender, due to the traditional machismo present in many aspects of Bolivian culture—but they also encountered prejudice and discrimination because of their ethnicity and social standing. It was the full set of these problems that dehumanized them in daily life. At the time, Bolivian culture offered few female leaders or instigators of social change who could serve as role models to empower and inspire indigenous women. They rarely had the opportunity to speak up and could not always muster the courage to act in opposition to injustice. Our hermanas, however, captivated as they were by the biblical narratives they read, assumed that the stories were theirs to emulate and embody, whether the characters were male or female.

One way in which Bible reading served to confer voice and autonomy on these women for the first time was when they shared and drew from Scripture in giving their testimonies. In Bolivian evangelical churches, testimonies delivered publicly by new believers had a powerful effect on the individual storyteller and the collective group. The testimony-giver took ownership of the biblical story in reflecting on her life before Christ, her present condition, and her future aspirations and dreams. I saw many indigenous women give powerful testimonies through gatherings that provided a rare opportunity for them to speak in public. In these settings, their identity was not only that of a wife, mother, or daughter. These women spoke about how they saw themselves as individuals in the eyes of God. As they grew in the faith and sought to follow the examples they encountered in Scripture, they also took action, and often went on to serve and even preach elsewhere in La Paz and Bolivia.

Scriptural inspiration and authorization of bold action is not a uniquely Bolivian phenomenon. What was perhaps different was how these women responded to challenging circumstances based on their reading of the Scripture, especially compared to nonbelievers in the indigenous community. Because these hermanas took the Bible seriously, they were emboldened to speak and act in ways that made them rare—and also highly effective as evangelists—among the indigenous community.

I met Hermana Juana during Bethesda School’s first year, when her oldest son, Juaquín, enrolled. She was a single mom of two young boys working a couple of days each week as a house cleaner. She herself had little formal education, having been taken out of school during the fourth grade and brought to the city by her older sister to work as a maid. Hermana Juana had struggled with depression after being abandoned by her husband. When she became a Christian, her love for the Scripture was insatiable. Over the two decades I knew her, I saw her transformed into a confident reader and eloquent preacher who was often invited to speak at various churches throughout the city and los campos. In Bolivia until recently it was not very common that someone like Hermana Juana would be seen speaking in public or in a position of leadership, but many evangelical churches now embrace female preachers from backgrounds like hers. Hermana Juana and others like her, having gained literary confidence, a sense of self-possession, and a boldness for action by reading her Bible, went on to inspire other women who followed suit.

Scholars note that today in North America many Christians can be seen dwelling in “the divided consciousness of simultaneously believing and not believing,”5 “‘on the cusp’ between belief and disbelief.”6 In this respect, for mis hermanas Bolivianas, being “on the cusp” is not an option. Poor indigenous women rarely receive encouragement or have the social proof to rise above their natural conditions. So they read the Bible with extra care, diligence, and interest as they discover its offer of not just salvation, but also of personal agency, of dignity, and of a role to play in the divine story. Like Hermana Juana, they take full ownership over the biblical narratives—improving themselves, speaking out, and serving the broader community beyond their own challenges and difficulties—because they intimately relate to the struggles of poverty, injustice, and discrimination that they encounter in the Bible. Scripture serves as a catalyst of growth and a source of encouragement to respond with bold compassion to those in society who have even less. It is a reminder to find God who dwells in the midst of ambiguity, and to act with audacity in the face of difficulties. These are the real, practical applications of hermeneutics on the ground, reading the Bible in Bolivia.