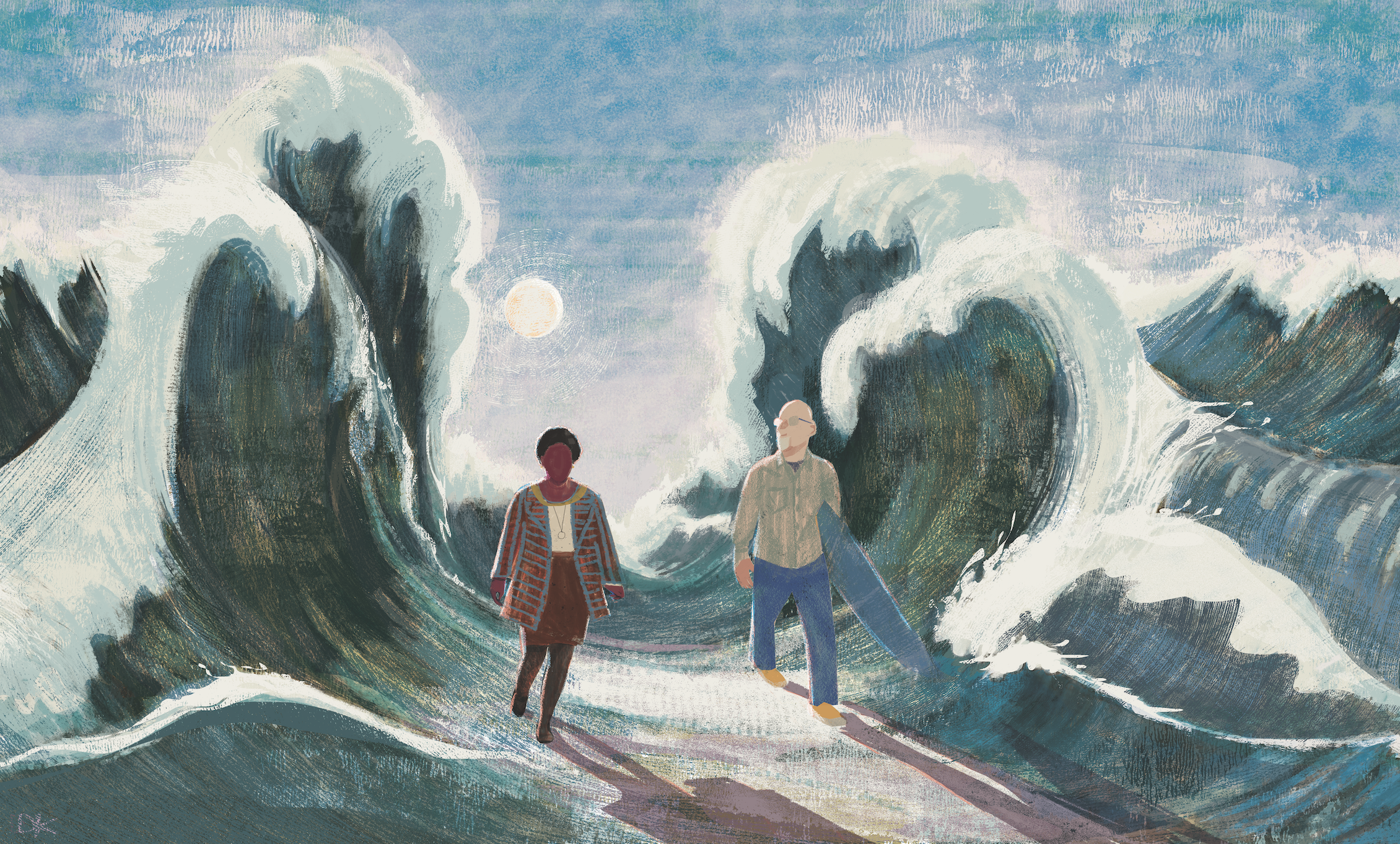

We are unlikely friends. But that is one of the most important things about our story. Western culture encourages people to insulate themselves from their own pain and from the pain of others, yet this has wreaked havoc on race relations in the United States. We have discovered that friendship between people who don’t look like each other can unite what our culture has divided, especially when that division runs along racial lines. Envisioning a future of racial justice that sets aside the pain of people in the name of progress is pure folly. Our friendship has allowed us to envision a better future, one that is rooted in the realities of our common and disparate experiences.

I (Teesha) am a younger Black woman, the child of immigrants. I am from Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, a diverse city that seems to encompass the laidback ethos of California, pumped up with Latin and Caribbean flavors and a Northeastern edginess. Although I regularly encountered people of various races and cultures, my race has never been incidental to life as an American. My parents went to great lengths to combat the social scripts that glorify European features as the standard for beauty, teaching my sister and me that our dark skin and kinky hair were beautiful. They also taught me not to open my purse inside a store so that I wouldn’t be accused of stealing. Whether in childhood, or later as an adult navigating life in the predominantly white and male field of law, being unconscious of my race was never an option.

I (John), an older white man, was born and raised in Southern California, in a racially isolated family. That changed when I attended Pepperdine University. Their Malibu campus was attractive to those of us who grew up surfing, and I began to surf with a fellow student named Bobby—the only Black surfer I’d ever met. Our friendship began to open my eyes to the realities of being a Black person in a white-oriented society. After graduating from Pepperdine, I began the MDiv program at Fuller. While there, the influence of professors Paul Jewett and William Pannell (among others) helped me to see that working against racism was indeed part of what it means to follow Jesus.

In 2013, I (Teesha) joined John on the staff of Buckhead Church in Atlanta, Georgia, working in the department John managed. As hoped, we worked well together and developed a sense of mutual trust and respect. A friendship slowly began to grow alongside our working relationship. I actually met my husband, Fred, in John’s office. Fred proposed to me in the exact spot where we first met, and a year later John officiated at our wedding.

Over time, our friendship grew as we talked about common interests—movies, theology, popular culture, even college football. Eventually we talked about race. The trust and respect that characterized our friendship up to that point continued to hold as we saw the world through the other’s eyes.

As we grew more confident in our ability to have trusting and respectful conversations about race, we tackled riskier topics. We talked about white fragility, Black people’s anger, systemic racism, and the intersection of race and poverty.1 We don’t always agree and sometimes an apology is necessary. But our friendship is not fragile. Friendship is an essential part of our journey as we follow Jesus into the messy, painful, and complicated reality that surrounds the 400-year history of racism in our country. That journey started with a friendship—but that’s not where it ends. Being honest about our pain, rather than setting it aside, is part of what sustains us. We’ve rejected a naïve vision of the future by naming and lamenting the past and present realities of racism in America.

As our conversations continued, we noted that many people hold to a narrow view of racism, one that is exclusively concerned with the conduct of individuals’ interactions with one another. From this perspective, a racist is someone who uses racial epithets or advocates violence against people of color. When racism is chiefly concerned with individual actions, we set a low bar for our conduct. We also absolve ourselves of any responsibility for addressing racism in a corporate sense. Our ethical standard becomes, “As long as I do not [insert act of personal racism here], then I am not part of the problem.” Part of seeing the future of race relations rightly is to see the present ways that racism manifests beyond personal interactions. We had to look at the ways that racism is embedded in our culture, laws, expectations, and institutions. In other words, we had to see racism as not just personal, but also as systemic, borne out in the racial disparities in life expectancy, wealth, educational opportunities, infant mortality, incarceration, and more.

Some American churches continue to harbor racism. In the midst of the controversy surrounding President Trump’s suggestion that certain members of Congress “go back where they came from,” the Friendship Baptist Church in Appomattox, Virginia, displayed a sign on their front lawn that read, “America: Love It or Leave It.” There are, of course, thousands of churches in the United States that understand the gospel calls for an explicit stance against racism. But there are still a concerning number that hide racism behind a religious veneer. Perhaps even more concerning are the churches that choose to remain silent on the issue. In doing so they fly in the face of God’s call to stand against injustice.

How does one acknowledge the ongoing presence of personal and systemic racism without losing hope? In some corners of Christianity, there is a tendency to avoid expressing pain to God, to one another, and even to ourselves. In the Hebrew scriptures, we find people faced with a crisis of theology and identity. Many of the psalms are written to address the forcible deportation of the people of Israel. This raised questions about Yahweh’s power and justice as they tried to make sense of why such a disaster had befallen God’s own people. The people of Israel responded through lament. Lament gives us a way to shake our fist at God, to grieve the many things that are not as they should be. I (John) found that as I cultivated a sense of holy discomfort and joined with Teesha in articulating her hurt and anger, the distance between us lessened. Lament can become a connective tissue that binds us to one another as it cultivates empathy.

Just as a clear vision of the future requires space for lament, there must also be room for anger. The summer of 2016 was one that sparked anger in me (Teesha). That summer, graphic video footage flooded social media of the July 6 police shooting of Philando Castile, a Black man, during a traffic stop. The horror of this event was punctuated by the July 5 killing of Alton Sterling, another Black man, at the hands of the police and the July 7 shooting of five Dallas police officers by a Black man in what appeared to be a racially motivated ambush. Anger gets a bad rap in Christian circles and in some senses that is with good reason. Anger can obscure the true meaning of our words and cause us to prioritize making a point at the expense of our friends’ needs. But righteous anger is appropriate in the face of injustice.

When I shared my anger with John over the deaths of these men, he listened without passing judgment. My openness about my anger and John’s willingness to listen made a way for love and empathy to grow. It helped ensure that our friendship was rooted in authenticity. It strengthened our resolve to experience hope together in the midst of harsh realities.

In a similar fashion, I (John) have had to own the fear that often plagues white people when they consider discussing racism with a Black person. There are sometimes valid reasons for this fear.

However, the fact that it is often the default position white people adopt has given rise to the phrase “white fragility.” This phenomenon includes more than a fear of anger. It also includes a reluctance on the part of white people to accept responsibility for the systemic racism that continues to plague the United States.

My experience with white fragility first occurred in 2007, when I was approached by a Southern Black man to set up a time to talk about racism. As I prepared for that conversation, I worried that I would be verbally attacked, blamed, or that I would say something hurtful. Thankfully, none of these things happened. The man, who became my friend, was honest yet gracious. That day I learned white fragility can only be overcome by choosing to engage in conversation. If you wait for it to go away before talking to people about racism, those conversations will never happen.

As we work to make sense of all the above, another Fuller professor comes to mind. George Eldon Ladd was professor of New Testament theology and exegesis at Fuller for over 25 years. Among his many important contributions to evangelical scholarship was his framing of the kingdom of God as both a present reality and a future apocalyptic order.2 In other words, the kingdom of God is already but not yet. This phrase gives us a way to make sense of the teachings of Jesus about the kingdom of God, but it also sums up the state of racial justice in the United States. It articulates a tension we must preserve. It draws a delicate balance that honors the work already done yet refuses to whitewash the racial dysfunction that continues to plague our country. It provides a place where we can lament without losing hope.

When we are willing to embrace the tension of already but not yet, we are oriented in a way that allows us to participate in what God has already done and yet continues to do. Simply put, the victory against evil—including racial evil—has already been won by Christ’s death and resurrection. But that victory is not yet consummated. Today the kingdom of God is advancing toward that consummation. That advance is the work of God in the world, often accomplished through human agency. That would be you and me.

I (John) recently asked a Black friend of mine if he thought things were getting better or worse. The friend, who has suffered as a Black man in this country, said that we’ve come a long way, but that we have a long way to go. I asked him what he saw that encouraged him. He said he saw a growing number of white people who were “getting real about racism.” He saw a lot of white people, whom he considers friends, pushing through white fragility into areas of meaningful conversation and action.

As a Black woman and a white man, we have experienced that kind of friendship. It doesn’t create a retreat where we can pretend that things are fine. Rather, it serves as a jumping-off point. Our friendship provides a platform where we can explore how to best address the personal and systemic racism that seems so deeply entrenched in our culture. In other words, friendship between people who don’t look like each other has the potential to disrupt racism, to create solidarity where there was once division, a common resolve where there was once only fear and anger. It creates a channel through which the kingdom of God can flow relationally, spiritually, and politically.

Friendship is a first step for anyone who wants to join the movement against racial injustice but doesn’t know where to begin. While you’re wondering whether or not you should march in the street, why not march across the street to your neighbor’s house and invite them to share a meal? That’s where it can start. God only knows where it will end.

Endnotes