“Hello, my name is Bruce and it’s been three weeks since my last fish—on my honor.”

Hello, Bruce.

Bruce is a shark trying to convince himself that “fish are friends,” parodying an Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting so familiar it can be found even in a children’s movie like Finding Nemo. It’s very well known, says Dale Ryan, associate professor of recovery ministry at Fuller, explaining that addiction recovery is “the largest explicitly spiritual popular culture movement in America since the second Great Awakening.” That explains why it is recognizable to film audiences young and old, but not why it is largely “off the radar of the evangelical church.”

The recovery movement “is rooted in the soil of American evangelicalism,” Ryan says, “but it’s the bastard child we don’t acknowledge.” Even though self-reliance is explicitly rejected in AA, with people encouraged to turn their lives over to something greater than themselves, fellowships like it are commonly perceived as self-help-driven—a perception that makes some uncomfortable. Fuller’s Institute for Recovery Ministry provides theological foundations for recovery work when the “higher power” is Jesus: helping pastors not to be afraid of or ignorant about addiction, and encouraging leaders who struggle with it themselves to model the honesty, integrity, forgiveness, and humility that the journey requires. At one time years ago, that included Dale Ryan.

The first AA meeting Ryan attended was for a class, and he arrived with a dose of seminary-fueled arrogance. “I felt pretty sure I was going to know more about God than anyone else,” he recalls, cringing.

Hello, Bill.

A man named Bill stood up and introduced himself. As he testified, a striking moment of clarity came for Ryan: How was it possible that Bill, who admittedly knew next to nothing about God, was having a genuine grace-filled experience when Ryan didn’t feel anything in his relationship with God but shame? “In many ways, Bill was at least half a step ahead of me in spiritual maturity,” Ryan remembers. That evening changed the course of his ministry and his life.

Ryan never imagined in 2004, when the recovery institute was established at Fuller, that ten years later he would host an evening of recovery stories that would include those of a past president of Fuller, the dean of students, and the dean of chapel and spiritual formation [+ their stories follow]. He told the audience that he felt a shift in the willingness of the evangelical community to acknowledge the important work of recovery and its widespread need—especially within its own communities.

It’s intriguing to imagine what might happen if the evangelical community were to reengage such a ubiquitous movement, how churches might be transformed by deeper levels of truthtelling, and how—by being honest about struggles of all kinds—they might provide safe places for people in recovery. It’s especially interesting since addiction, as Ryan defines it, is “anything you do to alter your mood. That might include alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, marijuana, sugar, power, control, heroin—even religion.” That’s why the institute has a recovery emphasis for most master’s degree programs, a certificate program, intensive think-tank experiences for ministry leaders, and a variety of other programs including a newly forming Fuller Alumni in Recovery group. Because the need is far-reaching.

Dean of Students Steve Yamaguchi attended his own initial group meeting more than 20 years ago, and he has enthusiastically invited pastoral colleagues to visit open AA meetings with him since, hoping to expand their imaginations of what spiritual fellowship can be. Most who joined him left awestruck and yearning: “I wish my church could be like that—so honest with each other.” There are millions of people around the world in weekly recovery meetings whose overt desire is to increase a conscious relationship with God, Ryan says. “They are kin to us. We are from the same tribe.” How many in the extended community of Fuller suffer in silence because of addictions they are too ashamed to reveal, Yamaguchi wonders. More, he thinks, than might be suspected. Many more, Ryan says, with a mixture of surety and care. “Many.”

Welcome to our meeting. Please introduce yourself.

It was the trying not to drink that was killing me more than the drinking. I knew without doubt that drinking again would destroy me, so I lived in fear and dread with severe self-imposed abstinences. It eventually consumed my every bit of energy. I became increasingly demanding and rigid—a monster to those close to me. I was pastor of a growing congregation. Our thriving revitalization gained wide attention. At the same time, my spirit was dying. I could no longer sustain the work by the power of my will and flesh. In the middle of apparent “pastoral success,” I hit bottom—spiritually, emotionally, psychologically.

A deacon in the church welcomed me to his AA meeting. A group of guys whom I immediately judged as low-life losers came to be, over the years, the voice of God in my life. The 12 steps of AA gave me a whole new way to taste and feel Jesus. Truths I had studied and taught became palpable. I discovered a freedom from fear and shame that opens a way to love and joy. It’s life over death. I’m so thankful.

+ Steve Yamaguchi is dean of students at Fuller.

Throughout my life as my pain surfaced, I would numb myself to keep from feeling anything. There wasn’t a week at Fuller that I wasn’t scoring my drug of choice. I would disappear into LA at night and emerge in Fuller housing before dawn. I felt immense shame about it. I was leading worship at a church and All-Seminary Chapel, and I even won a preaching award. I was living such a duplicitous life—I didn’t want to, but I just didn’t know who to talk to.Later as a pastor in Houston, I reached out to people with addictions, and as I realized how similar our stories were, I wept. I started going to meetings, but I was terrified that I would see someone I knew. Over time, I realized that facade needed to fade. It took some rigorous honesty, but I learned I wasn’t called first to be a pastor—I was called to be a fully alive and vulnerable person. I wouldn’t have learned that without these folks knowing my secrets and allowing me the space to fulfill my calling as a human being.

+ Matt Russell is affiliate assistant professor at Fuller Texas. See his full video interview here.

During my first teaching position, I was blacking out at parties, hiding booze, and lying about it. When my colleagues suspected that I had a problem and asked me to get help, I was furious. A few years later during a post-doc at Princeton, I was supposed to spend a year reading and writing, but I was drinking heavily instead. I realized this could be the year that I died—I just felt so hopeless. One night my wife saw me sneaking a drink, and I told her, “I’m an alcoholic.” She said, “What are you gonna do about it?”

The next morning she prayed with me, and I called the number for Alcoholics Anonymous. As I walked to my first meeting later that night, I sobbed and sang over and over again, “Just as I am, without one plea . . .” It was a profound spiritual experience. I went every day for three months. Those AA meetings were just liberating for me, and this September, by God’s grace, I will attain the goal of 40 years of sobriety. I truly believe the 12-step movement is preaching a sermon to the church, and it can expand our sensitivities to ministry and shed light on the realities of the human condition.

+ Richard J. Mouw is past president of Fuller and current professor of Faith and Public Life. See his full video interview here.

When I was a stepmother, I wanted to bring healing and health to my family. I thought if there was enough prayer and psychological expertise, it could be fixed. When we finally told our stepdaughter that she couldn’t keep using cocaine and living in the house, I hit rock bottom. When she screamed and swore at us as she left, I knew I had failed. My ability to wrap the family in love and heal everybody clearly had not worked.

When we went to an Al-Anon meeting the next day, I felt so broken. One of the first things someone said was, “We can’t allow other people’s choices to rob us of our serenity.” I wept. I had no serenity; for years I cloaked my anxiety by trying to do everything right, but what I realized was my serenity—my grounding in Christ and sense of my own life—was missing. It was such a revelation: my own life was short-circuited as I had tried to fulfill the needs of others. Now in my work at Fuller I want to help people feel free from that misunderstanding of love.

+ Laura Robinson Harbert is dean of chapel and spiritual formation at Fuller. Al-Anon is a support group for families. See her full video interview here.

I didn’t go to my first AA meeting because I thought that I needed to—I went because it was a class assignment in seminary. I was in my last year of an MDiv, and I remember feeling like I had reached the advanced levels of Christianity. I took this spiritual grandiosity to the AA meeting, and I remember wondering why I was asked to be there. I was pretty sure I knew more about God than any of the street drunks who showed up that night. One member was celebrating 30 days of sobriety, and he spoke about his gratitude and eagerness to learn about this Higher Power who was making it possible.

What confused me was this: he was having a transformational experience, but I, so sure of my knowledge of God, was only experiencing shame. I mark that evening as a turning point in the trajectory of my spiritual life. After that night, I began to see that I had made an idol for myself—a god of impossible expectations—and I began to move away from self-reliance and arrogance to a more graceful place. I’m deeply grateful for that.

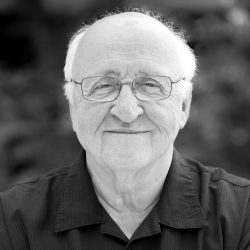

+ Dale Ryan is associate professor of Recovery Ministry at Fuller. See his full video interview here.