Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen (MAT ’89), professor of systematic theology, has been a member of Fuller’s faculty since 2000. In 2017, he completed a monumental five-volume project, A Constructive Christian Theology for the Pluralistic World, an extensive exploration of the traditional Christian doctrines that engages deeply with world religions and a breadth of contemporary issues. Since, he has also written two classroom-accessible textbooks based on the five volumes: Christian Theology in the Pluralistic World: A Global Introduction, released this past summer, and Doing the Work of Constructive Theology: A Primer for Christians, forthcoming in 2020 (all published by Eerdmans). We spoke with Veli-Matti about his groundbreaking work and how he envisions the task of theology today.

JEROME BLANCO: In the last few years, you completed a tremendous five-volume work on constructive theology. Your newest book, Christian Theology in the Pluralistic World, was released this summer, and you’ve got another one on the way. You’ve written that a goal of yours is to engage with issues largely ignored by many traditional systematic theologies—to more deeply engage with the cultural, ethnic, sociopolitical, and religious diversity in the world. Is this a necessary way of doing theology in today’s day and age? How did you come to see the need for this type of scholarship?

VELI-MATTI KÄRKKÄINEN: I came to write constructive theology in a “new key” through several “conversions.” I was first awakened to the need to write from an interconfessional—that is, ecumenical—perspective because no one Christian tradition has it all! The second conversion was intercultural, as I moved with my family to live and teach theology in Thailand, where even after learning Thai and teaching in it, I found it challenging to communicate theology to my Asian students. The third conversion was also initiated in Thailand, which is a multireligious country and a “homeland” to Theravada Buddhism. I realized there that theology had to be taught and written with an interreligious perspective. Engaging other living faiths is necessary, even when presenting and arguing for the Christian tradition.

Upon arriving at Fuller about 20 years ago, I soon realized that an interdisciplinary perspective had to be robustly adopted into developing Christian theology. How else could you speak, for example, about the doctrine of creation or of humanity? Sciences have much to say about the origins and workings of the world and us as human beings. I began to envision a totally new way of doing theology, namely constructive theology, which would incorporate these various perspectives into the standard theological discussion—which is based on biblical, historical, and contemporary theologies, as well as philosophy. At the same time, I noticed that the third millennium was calling theologians to take much more seriously the surrounding cultural milieu of the globalized world in which we live. Alongside cultural and scientific contexts, there are a number of issues that are deeply theological in nature even though Christian theology has ignored them by and large—particularly in typical systematic theology. These include the environment, poverty, violence and war, peace and reconciliation, gender, entertainment, and so forth. If God is the Creator of all—as we Christians believe—then nothing is outside the theological interest. Doing theology in this new key does not mean leaving behind or undermining the rich theological tradition based on the Bible, creeds, and cumulative doctrinal development. Even the most recent constructive theology has to be based on and engage critically with tradition. At the same time, a keen focus on current issues also helps retrieve tradition in a more relevant and exciting manner.

JEROME: It makes sense that multiple factors over a long period of time shaped your understanding. In that vein, writing can often be perceived as a very solitary act, yet it took multiple influences outside of yourself to arrive at this sort of theology. Additionally, by engaging in issues like those you mention, you must have had to seek out an incredible number of conversation partners. Can you speak to the communal aspect of writing these works? What was it like to engage with so many disciplines and voices outside of your academic expertise?

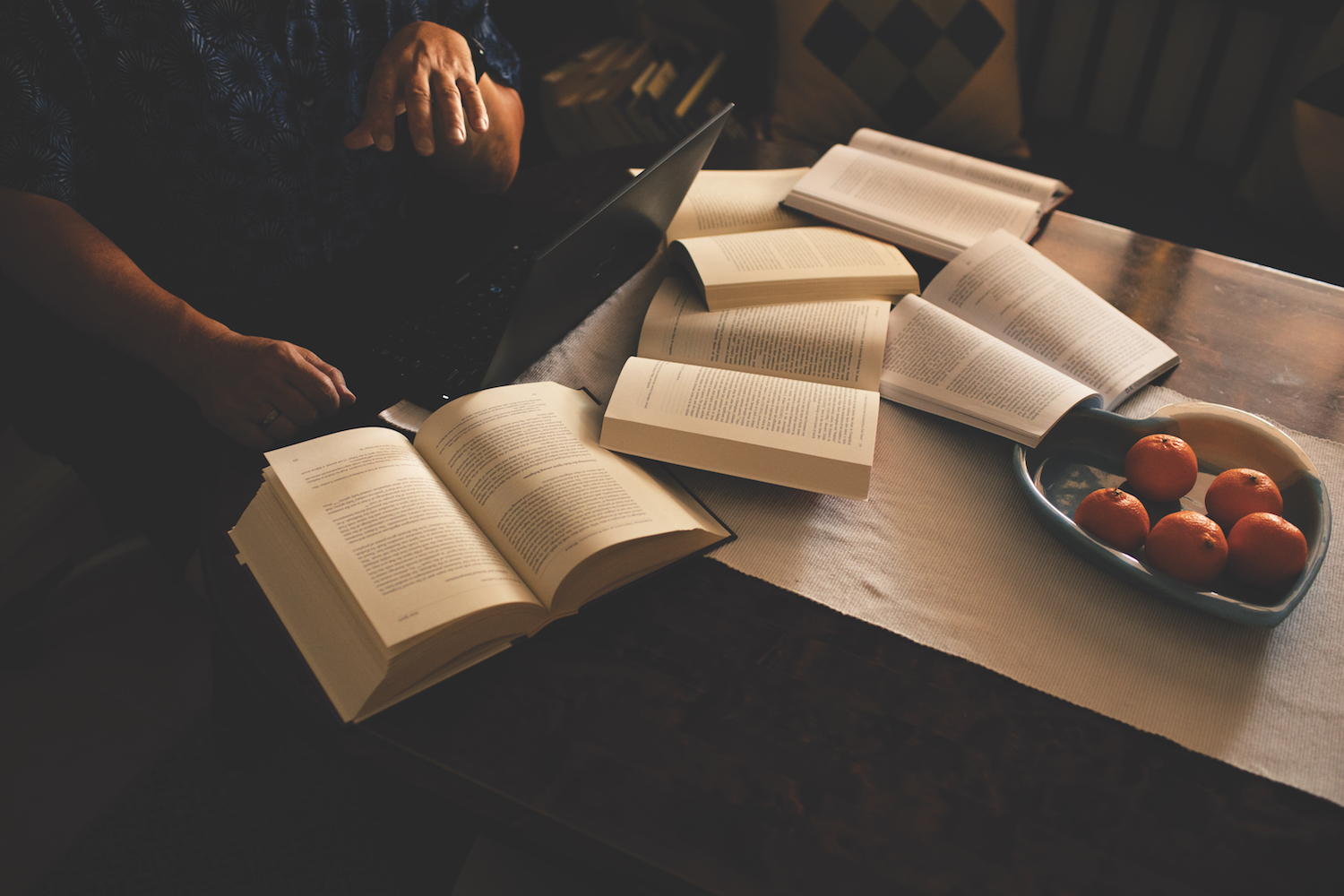

VELI-MATTI: Sure, the actual writing process—particularly of this magnitude—is a solitary act. For the sake of curiosity, let me mention that rather than at my Fuller office or home office, I do all of my academic writing at one end of our dining room table! Years ago, when our children were still with us, the large dining room table also had them doing their homework and my wife, a teacher, working on hers. For me a “solitary” act of writing has this nuance!

That said, everything that goes into doing and writing theology gleans from wide and diverse scholarly engagement. Because I write in an interdisciplinary—and even interreligious—perspective, over the years I have had to consult, learn from, and discuss topics with experts in different fields of academic study. For example, when it comes to natural sciences, I have benefited greatly from collaboration with institutes and their scholarly networks of scientists, such as the Center for Theology and Natural Sciences at Berkeley, headed by Robert J. Russell. I have also learned a lot about neuroscience and philosophy of mind from having cotaught doctoral seminars with Fuller’s own Nancey Murphy and Warren Brown, as well as in a semester-long interdisciplinary sabbatical at Biola’s Center for Christian Thought. Regarding world religions, I have learned a lot from having cotaught the course that I created about 15 years ago, World Religions in Christian Perspective. Similarly, doctoral mentoring of students who have worked in the intersection of, say, Islam and Christianity, or Buddhism and Christianity, has enriched my own knowledge.

The six-year project of creating the Global Dictionary of Theology was particularly important for beginning to establish a wide network of scholars from all over the world. With my Fuller colleagues Bill Dyrness and Juan Martínez, almost 200 scholars from all continents worked together to write this massive dictionary. My continued teaching position at the University of Helsinki, my alma mater, also keeps me widely connected with European and continental scholarly networks. Similarly, my unusually busy international traveling to conferences, academic and theological/ecumenical consultations, and speaking engagements all over the world helps create and sustain scholarly relations.

In sum: I would not have been able to do anything like what the five-volume set is without these various scholarly communities and collaboration.

JEROME: The whole task is an incredible communal act then! As it should be, being a work done in, with, and for the church. Speaking of the wider church, your recent and forthcoming books are both textbooks, meant to be more accessible to wider audiences. People can sometimes be skeptical about the positive impact academic theology can have on the church on the ground. Surely you’re no stranger to such sentiments. What have been your hopes for how your work can contribute tangible transformation to the wider church? How has the writing of your constructive theology transformed you not only as a scholar but in your everyday life as a Christian disciple?

VELI-MATTI: One of the things I am deeply concerned about in the current academic world is the often-too-thin connection between theologians and the church. This is an oxymoron, so to speak. What we nowadays call “theology” was birthed and developed for hundreds and hundreds of years by pastors, bishops, and other church leaders, rather than academicians. It was only after the Enlightenment that one could be a theologian without being a “church(wo)man.” Particularly concerning to me is the rise of a new generation of younger theologians distanced from the church—sometimes even intentionally.

I am an ordained clergyperson in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America and preach, teach, and do services and pastoral duties all the time, including mentoring pastoral candidates. I was first ordained in my native land—Finland—the very same year I finished my first academic degree in theology decades ago!

Since, I have been engaged in church work. I know many doubt the relevance of academic theology for the church. And we theologians are to blame for it to some degree. At the same time, we have to remember that “relevance” does not mean that you just learn some simple “things” that easily apply to ministerial problems. The relevance of theological education has to do with a lifelong shaping of the minister, and through the minister, the community. When I preach to the congregation—and I do so regularly, unlike most contemporary theologians—I do not “speak theology.” I preach. But my sermons are formed by my lifelong study of theology. My counseling of the sick and the bereaved is similarly shaped by my studies, alongside experience. And so forth. A good pastor-theologian is able to educate and train leaders and volunteers in the church through the scholarship she or he has acquired. That kind of pastor is able to “translate” to the local context a high-level academic theology and put it into work. My own spiritual formation and church ministry have benefited tremendously from the lifelong study of theology. And I can’t think of a better way to enrich, challenge, and develop the minister’s aptitude than the continual study of theology, alongside active ministry and spiritual disciplines.

JEROME: Do you have hope that the church and the academy will be able to push back against this separation and distancing in some way? How would you address it?

VELI-MATTI: I think it is very important to see both the integral link between the church and theological academia and their distinction. Regarding the former, I often ask my colleagues and students: What would you think of training medical doctors without continuing work and practice in the hospital? Could you be a professor in a medical school with little or no experience and continual work in the hospital? This same observation relates to training ministers and leaders for the church. I have fears about how a close connection with the church is not a requirement for the instructors and professors in theological schools. It is left to the choice of the individual professor whether to work in a congregation alongside their academic work. And too often, it is mistakenly assumed that the “practical” aspects of the training—especially in the MDiv—will be taken care of by one department of the seminary, namely the Division of Ministerial Studies, and that others (e.g., theology and history) do not have to worry about it. That is really a mistaken assumption and should be challenged. I am urging theological schools and educators to forge closer links with the church and church life. And I am encouraged by the growing calls to the same effect in various quarters of the theological training world.

Concerning the distinction (though not a separation) between the church and academia: Graduate school theological education has a particular task and mandate to teach theology based on high-level academic research and learning. That the theological school should be “relevant” for the church does not mean that therefore it should focus mostly on “practical” matters. In this regard, I am very proud of Fuller, where we value high-level research and academic publication, which is made possible to a large extent by our unusually generous research sabbatical program.

A part of the theological school’s academic, research-driven mandate is also to sympathetically critique, challenge, and at times even confront teachings, practices, and phenomena in congregations that seem to be problematic or erroneous. Critical thinking belongs to the very essence of academic work—and it does not have to be “negative” at its core but rather a tool for helping churches develop and improve.

JEROME: Circling back then to your recently published and forthcoming books, which touch on a wide range of issues, are there matters in the church today that you believe such critical thinking must most urgently address? Or, to put it another way, are there specific new or underexplored frontiers where you really hope to see such innovation in the church’s theological and ministerial approach?

VELI-MATTI: In my understanding, the single most important issue for the church and theological academia has to do with religious plurality. It is astonishing that, even today, major systematic theological studies are published, doctrinal presentations given, and church sermons delivered as if the world we live in consisted of only two kinds of people, the “sinners” and the Christians! That is of course not the case: the church and academia find themselves living in a deeply religiously pluralistic world and in a world in which secularism is also gaining a stronghold. My own five-volume constructive theology as well as the two most recent textbooks are unique in that they integrate the dialogue with other faith traditions into the matrix of doing “normal” Christian theology. I believe that something similar to what I have done, namely including interfaith comparisons into the discussion of all Christian doctrines, may well become the norm in the near future. The great challenge here is that very, very few theologians are knowledgeable about other faiths. Our theological education has to equip them with such knowledge.

And as I mentioned earlier, there are also topics that have been so far ignored in typical systematic theological investigations, including violence, the environment, gender, power, war, peace, entertainment, and so forth. Among the topics usually not included in Christian doctrine—alongside other faith traditions—is the relation of Christian faith to natural sciences. Sciences dominate the consciousness of the contemporary world and have extremely important lessons to teach us. Additionally, among many innovations at Fuller, I am extremely proud of our Brehm Center, which integrates theology with film, entertainment, literature, and pop culture. These cultural spheres exercise an amazing influence on the global world. All these things merit careful theological reflection, and they all belong to the “standard” theological menu.