Labels may be necessary, but they seldom seem adequate. When we use labels, our minds and spirits easily give way to stereotyping and reductionism. But since we can’t give up our labels, it is important from time to time to examine them and to make them as clear as possible, to distinguish what we mean and what we don’t mean.

In what ways, then, is “evangelical” a key label in the identity and mission of Fuller Theological Seminary?

THEOLOGY

When we confess ourselves to be “evangelical,” we are making affirmations that point toward the centrality of the gospel: the revelation of God in Jesus Christ through whose saving life, death, and resurrection we are adopted into God’s family, given God’s Spirit, and called to live together under God’s reign. This is the “good news” to which Scripture points us with supreme authority and faithfulness. When Fuller Seminary affirms that we are “evangelical,” this is what we confess, and we do so with earnest faith, intellectual commitment, scholarly inquiry, confessional trust, and communal hope.

This essential understanding of “evangelical” does not always rest easily among some of our brothers and sisters who also identify themselves by this name, using, it might be said, a less lean set of descriptors. They use “evangelical” to include a further set of definitions and commitments related, for example, to the nature of the atonement, to the inspiration and authority of the Bible, to the baptism of the Holy Spirit, and to the eschatological hope of the kingdom. Apart from debates in the 1970s over the change in our Statement of Faith from “inerrancy” to “infallibility” regarding Scripture, these other definitional debates have not been core to Fuller’s history.

Using “evangelical” to describe our theological orientation keeps us rooted in what Fuller has understood to be the good soil of Christian orthodoxy, in which personal and communal faith can flourish for us as disciples and witnesses who testify to and demonstrate the incarnational, transformative love, righteousness, and justice of God in Jesus Christ. All that we do as an institution is done in the context of this theological vision and frame.

CHURCH

When “evangelical” refers to a community of Christian believers, it is typically an adjective that describes the core of their theological commitments, not a description of their denominational affiliation or ecclesial structures. “Evangelical” congregations can be found in many different denominations, from nondenominational to Baptist to Presbyterian to Episcopalian and more.

This has certainly been an aid for Fuller as a multidenominational seminary that draws people from over 100 denominations into one faculty and student body. “Evangelical” has been a term of welcome to people who come from a very wide spectrum of ecclesial and congregational practices, whether of governance or of sacraments or of liturgy.

In this sense, “evangelical” has been a valuable term that highlights and names what we at Fuller believe is the heart of the Christian faith, the center from which our biblical, theological, historical, cultural, psychological, and vocational formation and reflections unfold. It names what I mean when I say that we are an institution with roots in orthodoxy, the roots that explain the life that is in the church.

CULTURE

“Evangelicalism” can also refer to Christian subculture(s). This is no monolith, but rather a wide variety of social, economic, and political views and associations. Each expression reflects a way of seeing and interacting with culture and might be politically left or right, ethnically mixed or homogeneous, rich or poor.

The Fuller community includes many expressions of “evangelical” subcultures. This is what makes conversations at Fuller often so robust and valuable as we learn to listen to and hear one another. It also explains why such conversations can be confusing when we think a particular subculture is the only genuine expression of evangelicalism.

The media stereotyping within and around “evangelicals” can suggest that the name applies to one view of social ethics—relating to, for example, abortion or homosexuality. This view is reinforced within some evangelical ranks where it is believed that the theological convictions that guide evangelicals lead to one consistent conclusion regarding such issues.

Many in evangelical subcultures are uneasy acknowledging that the Bible’s authority and the Bible’s meaning are not synonymous or necessarily transparent. Faithful listening and reflection under the authority of Scripture and in response to the Lordship of Jesus Christ does not mean unanimity or easy unity. The same is true for the whole church, and it is also true for those who call themselves “evangelical.”

Fuller Theological Seminary is an “evangelical” institution that gratefully and faithfully benefits from this central theological affirmation. I take it for granted that making this confession does not make such faith uncontested, and that we can and must continue always to wrestle with the complexity and windswept landscape in which we speak and live such a hope—for the sake of the church and the world.

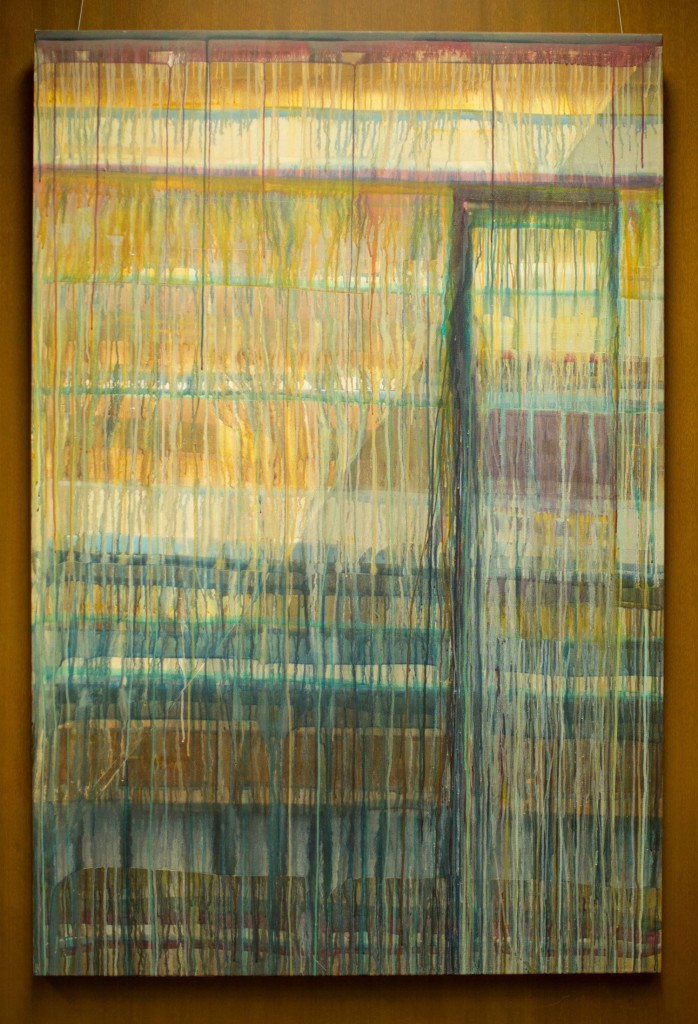

+ Exodus IX (2005) acrylic on canvas Caron G. Rand . Artwork by Rand, a friend of Fuller, was exhibited in Fuller Pasadena’s Payton Hall where weekly chapel is held.

Usar etiquetas puede ser necesario aunque pocas veces sea adecuado. Cuando usamos etiquetas, nuestra mente y espíritu fácilmente dan paso a los prejuicios y estereotipos. Pero ya que estamos acostumbrados a las etiquetas y no podemos renunciar a ellas, es importante examinarlas de vez en cuando para distinguir claramente lo que queremos y no queremos decir.

“Evangélicos” es una palabra que implica valores y problemas, inclusive para los que se identifican con esa terminología. Su significado es variado y debatido, sus afinidades pueden ser simultáneamente de amor, aprecio, controversia y confusión. Muchos se pueden preguntar: ¿El término “evangélicos” continúa siendo una designación útil? Si es así, la pregunta más importante es: ¿Qué significa la palabra “evangélicos” para la identidad y misión del Seminario Teológico de Fuller?

Teología

Cuando confesamos ser “evangélicos”, estamos afirmando el punto central del evangelio: Jesucristo es la revelación de Dios, mediante el podemos ser salvos y librarnos de la muerte. Mediante su resurrección y ascensión hemos sido adoptados a la familia de Dios dándonos su espíritu y llamándonos a vivir juntos en el reino de Dios. Estas son las “Buenas Nuevas” que mencionan las escrituras con una autoridad suprema y fidedigna. Cuando el Seminario Teológico de Fuller afirma que somos “evangélicos”, estamos confesándolo y lo hacemos con una fe ferviente, con un compromiso intelectual, una confesión verdadera, un propósito misionero y una esperanza de toda la comunidad.

Este entendimiento esencial de “evangélicos” no siempre es fácil entre algunos hermanos y hermanas que también se identifican usando este nombre, se podría decir que es un conjunto de descripciones menos “sesgada”. Se puede utilizar la palabra “evangélicos” para incluir una serie de definiciones y compromisos relacionados entre si, por ejemplo, la naturaleza de la expiación, la naturaleza de la inspiración y autoridad de la Biblia, el bautismo del Espíritu Santo y la esperanza escatológica del reino de Dios. Aparte de los debates de la década de 1970 que trataban sobre el cambio en nuestra declaración de Fe de la “inerrancia” a la “infalibilidad” de las Sagradas Escrituras, estos debates de las definiciones no han sido centrales para la historia del Seminario Teológico de Fuller.

Identificándonos como “evangélicos” para describir nuestra orientación teológica, nos mantiene unidos a lo que Fuller ha entendido como el buen terreno de la Ortodoxia Cristiana. En la Ortodoxia Cristiana, la fe personal y comunitaria pueden florecer y prosperar para nosotros como sus discípulos y testigos quienes testificamos acerca del amor transformador de la encarnación, justificación y redención de Dios en Jesucristo. Todo lo que hacemos como institución se hace en el contexto de este marco y visión teológica.

Iglesia

Cuando confesamos que somos “evangélicos”, estamos afirmando que somos miembros de una iglesia que trasciende las afiliaciones denominacionales o estructuras eclesiásticas. Los “Evangélicos” comparten simultáneamente una serie de creencias centrales y unidad las cuales promueven una misión común. Las congregaciones “evangélicas” se pueden encontrar en muchas denominaciones, desde las no denominacionales a los Bautistas, Presbiterianos, Episcopales y otras.

Ciertamente esto es real para Fuller por ser un seminario multidenominacional con más de 100 denominaciones que forman el cuerpo estudiantil y de la facultad. “Evangélicos” ha sido una terminología de hospitalidad para las personas procedentes de un variado espectro de practicas eclesiásticas y congregacionacionales, forma de gobernanza, de los sacramentos, o de las liturgias, pero han encontrado una comunidad que participa de la misma orientación teológica.

En este sentido, “evangélicos” ha sido una terminología valiosa que destaca y nombra lo que en Fuller creemos es el corazón de la fe cristiana-“el evangelio”-las buenas nuevas- el centro donde nuestra formación vocacional, bíblica, teológica, histórica, cultural, psicológica y acciones profesionales se forman y desarrollan. Esto es lo que quiero decir cuando digo que somos una institución con raíces ortodoxas: Nosotros estamos arraigados en el evangelio que se ha estado pasando y viviendo en nuestra comunidad a través de las edades y en cada generación.

Cultura

Cuando confesamos que somos “evangélicos”, estamos afirmando que dentro de la unidad de la iglesia hay distintas subculturas cristianas. El Evangelicalismo no es monolítico, dentro de la tribu evangélica encontramos una amplia variedad de aspectos sociales, económicos y la asociación de diversos puntos de vistas. Cada expresión refleja una forma de interactuar con la cultura, la política puede ser de izquierda o derecha, étnicamente mixta u homogénea, rica o pobre.

La comunidad de Fuller incluye muchas expresiones de subculturas “evangélicas”. Esto contribuye a que las conversaciones de Fuller sean generalmente más sólidas y valiosas a medida que aprendemos y nos escuchamos unos a otros. También encontramos que este tipo de conversaciones pueden ser confusas si se piensa que una subcultura en particular es la única expresión genuina del evangelicalismo.

El estereotipo central dentro y fuera de los “evangélicos” puede sugerir que el nombre se aplica a la relación ética social, por ejemplo, el aborto o la homosexualidad. Estos puntos de vista están reforzados en algunas filas evangélicas donde se cree que las convicciones teológicas que guían los evangélicos los conducen a una conclusión segura y coherente con cualquier asunto de importancia.

En algunas subculturas evangélicas, muchos se sienten incómodos al reconocer que la autoridad y significado de la Biblia no son necesariamente transparentes ni sinónimos. Escuchar fielmente y reflexionar bajo la autoridad de las Sagradas Escrituras en respuesta al Señorío de Jesucristo no significa necesariamente una fácil unidad ni uniformidad. Por supuesto, lo mismo es cierto para toda la iglesia y también es cierto que todos los que se llaman a sí mismos “evangélicos”.

El Seminario Teológico de Fuller es una institución “evangélica” que se beneficia con fidelidad y gratitud de esta afirmación central, histórica y teológica. Esta confesión no hace que la fe sea indiscutible. Podemos y debemos seguir luchando siempre con la complejidad de los vientos que azotan el paisaje en el que hablamos y vivimos con una esperanza- por el bien de la iglesia y del mundo- y por la “Buenas Nuevas” que gozosamente proclamamos, la realidad a la que cualquiera buena etiqueta señalará.

+ Exodus IX (2005) acrylic on canvas Caron G. Rand . Artwork by Rand, a friend of Fuller, was exhibited in Fuller Pasadena’s Payton Hall where weekly chapel is held.

이름표는 필요하기도 하지만 그것만으로 충분한 것 같지는 않습니다. 이름표를 사용할 때, 우리의 생각과 정신은 쉽게 고정관념과 환원주의에 빠지게 됩니다. 우리가 이름표를 포기할 수 없다면 가끔은 그것들을 점검하여 가능한 한 명확히 해 두는 것이 중요합니다. 이름표를 통해 우리가 의미한 것과 그렇지 않은 것을 구분하기 위해서 말입니다.

“복음주의”라는 말은 가치와 문제점을 모두 지니고 있습니다. 자신을 복음주의라고 생각하는 사람들 간에도 그 해석은 다양하며 토론의 주제가 됩니다. 이 단어가 갖는친근감이 사랑받고 소중히 여겨지는 동시에논쟁과 혼동의 대상이 되는 것입니다. 많은 사람이 “‘복음주의’라는 말이 여전히 유용한 명칭입니까?” 라고 묻는 것도 그리 놀라운 일이 아닙니다. 여기서 가장 중요한 질문은 이것입니다. “그렇다면, 풀러신학대학원의 정체성과 사명에 있어서 “복음주의”라는 이름표는 무엇을 의미하는 것입니까?”

신학

우리가 자신을 “복음주의”라고 고백할 때, 우리는 복음의 중심성을 확증하는 것입니다. 즉, 예수 그리스도 안에 나타난 하나님의 계시, 그분의 구원의 생명, 죽음, 부활, 그리고 승천을 통해 우리는 하나님의 가족으로 입양되고, 하나님의 영을 받아, 하나님의 통치 아래 함께 살도록 부르심을 입는다는 선언입니다. 이것이 “복음”이요, 성경이 절대적인 권위와 신실함으로 우리에게 증거하는 바입니다. 풀러신학대학원이 스스로 “복음주의”라고 주장할 때, 이것이 우리의 고백이며, 우리는 진실한 믿음과 지적인 헌신, 진정한 신뢰, 선교적 목표와 공동체적 소망으로 그렇게 고백하는 것입니다.

“복음주의”에 대한 이와 같은 본질적인 이해가, 덜 “간결한” 서술어들을 사용하여 자신들을 복음주의라고 간주하는 우리의 지체들 사이에서 항상 쉽게 받아들여지는 것은 아닙니다. 그들은 “복음주의”라는 이름에, 예를 들어 속죄의 본질, 성경의 영감과 권위의 본질, 성령 세례, 그리고 하나님 나라에 대한 종말론적 소망에 관계된 더 넓은 정의들과 약속들을 포함하고자 합니다. 우리의 신앙 선언문에서 성경에 관하여 “성경 무오”에서 “성경 무류”로 전환한 것과 관련한 1970년대의 논쟁들을 제외하고는, 이러한 다른 개념적 논의들이 풀러 역사의 중심에 놓인 적이 없습니다.

우리의 신학적 지향을 묘사하기 위해 “복음주의”라는 이름을 사용하는 것은 풀러가 개신교 정통의 좋은 토양이라고 이해해 온 것에 뿌리를 두게 합니다. 다시 말해, 개인적이고 공동체적인 신앙이 우리로 예수 그리스도 안에 있는 하나님의 성육신적이고 변화시키는 사랑, 의로움, 공의를 증거하고 증명하는 제자요, 증인으로 번성하게 하는 토양 말입니다. 학교로서 우리가 하는 모든 것이 바로 이러한 신학적 비전과 틀 안에서 이루어지는 것입니다.

교회

우리가 자신을 “복음주의”라고 고백할 때, 우리는 교파적 배경이나 교회의 구조들을 초월한 하나의 교회에 속한 일원임을 선언하는 것입니다. 이러한 이유로 “복음주의자들”은 공통의 핵심적 신앙과 일체감과 사명 모두를 함께 나눕니다. “복음주의” 회중들은 교파에 속하지 않은 교회는 물론, 침례교, 장로교, 성공회 등 다양한 교파들에서 찾아볼 수 있습니다.

초 교파적 신학 대학원으로서의 풀러는 백 개가 넘는 교파의 사람들을 하나의 교수진과 학생 조직으로 모았다는 점에서 진정한 복음주의 학교임이 분명합니다 “복음주의”라는 이름이 체제나 성례나 예배의식이 서로 다른 매우 광범위한 교회적, 회중적 관습을 갖고 있음에도 불구하고 공유된 신학적 지향 안에서 공통의 공동체를 발견한 사람들에게 환대의 개념이 되어 주었던 것입니다.

이런 의미에서 “복음주의”는 풀러가 믿는 것이 개신교 신앙의 정수, 즉 “복음”이라는 것을 강조하고 명명하는 가치 있는 용어가 되어 왔습니다. 이 복음이 우리의 성경적,신학적, 역사적, 문화적, 심리학적, 그리고 소명적인 형성과 실행이 전개되는 중심이라는 신앙의 고백입니다. 이것이 우리가 정통에 기반을 둔 학교라고 말할 때 제가 의미하는 바입니다. 우리의 뿌리는 시대를 거쳐 모든 세대의 공동체를 통해 전해 내려오고 살아져 왔던 복음에 있습니다.

문화

우리가 자신을 “복음주의”라고 고백할 때, 우리는 교회의 통일성 안에 독특한 개신교 소 문화들이 존재하고 있음을 확언하는 것입니다. 복음주의는 하나의 거대한 단일 조직이 아니며 복음주의 집단 내부에도 다양한 사회, 경제, 정치적 견해와 유대들이 존재합니다. 각각의 표현은 문화를 이해하고 교류하는 방식을 반영하며 정치적으로 좌파 혹은 우파일 수도, 인종적으로 혼합되었거나 동족일 수도, 가난하거나 부유할 수도 있습니다.

풀러 공동체는 “복음주의” 소 문화들의 많은 표현을 수용합니다. 이것이 서로에게 귀 기울이는 것을 배우는 풀러에서의 대화를 흔히 매우 생기있고 가치 있게 만드는 이유입니다. 이것이 또한 만약 누가 특정 소 문화가 복음주의의 유일하고도 진정한 표현이라고 여긴다면, 왜 이러한 대화가 혼돈에 빠질 수도 있는지를 설명해 줍니다.

“복음주의자들” 내부나 그들을 둘러싼 미디어의 정형화는 이 이름이, 예를 들어 낙태나 동성애에 관련된 사회 윤리 중 하나의 견해에 해당한다고 암시할 수도 있습니다. 이러한 견해는 복음주의자들이 따르는 신학적 신념들이 어떤 중대 사안에 관하여 하나의 지속적인 결론을 도출하게 한다고 믿는 일부 복음주의 계열 내부에서 강화되고 있습니다.

일부 복음주의 소 문화 안에서 많은 이들이 성경의 권위와 성경의 의미가 동일하지 않다거나 혹은 반드시 명백한 것은 아니라는 주장을 인정하기 불편해합니다. 성경의 권위 아래 예수 그리스도의 주인 되심에 반응하는 신실한 경청과 반성이 반드시 만장일치나 쉬운 통일을 뜻하는 것은 아닙니다. 물론, 교회 전체에 대해서도 마찬가지이며 자신을 “복음주의”라고 칭하는 사람들에게도 동일하게 적용됩니다.

풀러신학대학원은 이러한 중심적인, 역사적, 신학적 주장으로부터 겸허하고도 신실하게 유익을 얻는 “복음주의” 학교입니다. 이러한 고백이 있다고 해서 그런 신앙이 도전받지 않는 것은 아닙니다. 우리가 맞서 싸워야 하는 현실은 복잡하고 강한 바람이 몰아치는 거친 환경입니다. 그 안에서 우리는 교회와 세상을 위하여 그러한 소망과 우리가 기쁨으로 선포하는 “복음,” 즉 좋은 이름표가 가리키는 실제를 말하고 살아야 하는 것입니다.

+ Exodus IX (2005) acrylic on canvas Caron G. Rand . Artwork by Rand, a friend of Fuller, was exhibited in Fuller Pasadena’s Payton Hall where weekly chapel is held.