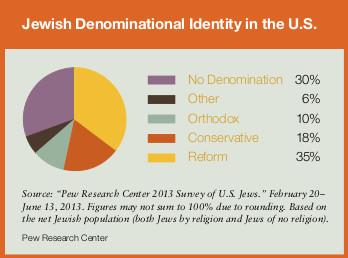

Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism evolved in early nineteenth-century Germany when Jews began integrating into German society on a large scale after having previously been confined to ghettos and subjected to discriminatory laws that limited their integration with their fellow countrymen.1 The Reform movement evolved out of an effort by European Jews to integrate their Jewish heritage with Western ideas and culture, wherever they could combine the two without conflicts.

Today’s Reform Jews have eliminated dietary restrictions and codes of dress. They do not await a personal messiah, believing instead that through its own progress, humanity will accomplish the messianic work of redemption.2 Reform Jews observe the Sabbath, albeit typically in a more relaxed manner than do members of most other Sabbath-observing Jewish movements. Reform Jews consider the Torah and Talmud to have been divinely inspired but influenced by humans, and tend not to see the commandments as binding.

Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism emerged as a distinct sect in mid-nineteenth-century Europe as a response to Reform Judaism; Orthodox Jews rejected the idea that Judaism was in need of reform.3 They consider the Torah (the Pentateuch) and the Oral Torah (the Talmud) to have divine authorship and the commands and wisdom therein be eternally applicable. Orthodox Jews aim to obey the letter of the law, though the details of some practices vary among Orthodox communities. For the Orthodox, the law consists of the Torah and Talmud only, though some commentaries are also authoritative.4

Orthodox Jews observe the Torah’s dietary laws, separate men and women in synagogue worship, and strictly observe the Sabbath. Synagogue services are led in Hebrew, and Orthodox Jews expect a personal Messiah to return to Jerusalem. Perhaps the factor that most distinguishes the Orthodox from other Jews is their commitment to premodern Judaism; from the Orthodox perspective, God authored both the Torah and the Jewish traditions, which makes them eternally perfect by definition.

Hasidic Judaism

Modern Hasidic Judaism was founded in Poland in the mid-eighteenth century by mystic rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov. Though it began a century before Orthodox Judaism distinguished itself from other Jewish movements, modern Hasidism is considered to be a type of Orthodox Judaism. Hasids can be distinguished from other Orthodox Jews by their unique clothing, their notable commitment to their leaders, and their interest in the “inner” (mystical) aspects of the Torah.

Conservative Judaism

Conservative Judaism developed in the mid- to late-nineteenth century as Zecharias Frankel led European Jews in reimagining Judaism as a faith that was capable of evolving in practice with modernity but which was rooted firmly in Jewish tradition.

Conservatives believe the Torah and Talmud to have divine roots, but unlike Orthodox Jews, Conservatives believe the books to have human influences as well. Unique to Conservative Judaism is its take on the Jewish law, halakhah; for Conservatives, halakhah includes not just the letter of the law, but also the spirit of the law.5 Because of this, Conservative religious practice can and does evolve, though the law is binding.6 Like Orthodox Jews, Conservatives observe the Sabbath and the dietary restrictions of the Torah, but unlike their Orthodox counterparts, they ordain women as rabbis, practice mixed-gender worship, and hold in high regard the halakhic process (discernment of Jewish law).

Conservative Jews tend to be quite supportive of the nation of Israel, believing it to be the ultimate destiny of all Jews. Hebrew is used in Conservative liturgy. There are varying beliefs within the Conservative movement regarding the existence of a personal Messiah.7

Reconstructionist Judaism

Reconstructionist Judaism was founded in the early twentieth century by an American rabbi named Mordecai Kaplan. Kaplan was a passionate champion of women’s rights, an issue that led him to believe that Judaism must be reconstructed (as opposed to merely reformed or conserved). Kaplan rejected supernaturalism altogether, eliminating as well in this new version of Judaism the notion that the nation of Israel was a chosen people.8 Kaplan defined Judaism as a “civilization” complete with food, customs, languages, and laws; because he did so, many irreligious Jews were inclined to join the movement.

Like Reform and Conservative Jews, Reconstructionist Jews seek to combine traditional Jewish culture and traditions with modern beliefs and ways of living. Reconstructionism rejects the concept of a personal Messiah and a divine origin of the Torah, and considers the halakhah (Jewish law) to be sacred but nonbinding.9 Despite the comparative lack of structure within the movement, Reconstructionism’s aim is to keep the faith’s history and tradition alive.

ENDNOTES

1The Movement for Reform Judaism website: http://www.reformjudaism.org.uk/about-us/what-is-the-history-of-reform-judaism.html.

3Rabbi Elaine Rose Glickman, “The Messianic Concept in Reform Judaism,” on the My Jewish Learning website, http://www.myjewishlearning.com/history/Modern_History/1700-1914/Denominationalism/Orthodox.shtml.

4Rabbi Louis Jacobs, “Orthodox Judaism,” on the My Jewish Learning website, http://www.myjewishlearning.com/history/Modern_History/1700-1914/Denominationalism/Orthodox.shtml?p=1.

5“Halakhah in Conservative Judaism,” reprinted with permission from Emet Ve’emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism, on the My Jewish Learning website: http://www.myjewishlearning.com/practices/Ritual/Jewish_Practices/Halakhah_Jewish_Law_

/Contemporary_Attitudes/Conservative.shtml.

6“Movements of Judaism,” in Torah 101, copyright Mechon Mamre, last updated 24 January 2012: http://www.mechon-mamre.org/jewfaq/movement.htm.

7Emet Ve’emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism, copyright 1988 by The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, by The Rabbinical Assembly, and by The United Synagogue of America; available at http://masortiolami.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Emet-VEmunah-Statement-of-Principles-of-Conservative-Judaism.pdf.

8“Reconstructionist Judaism,” archived BBC website content, Religions, last updated August 13, 2009, http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism/subdivisions/reconstructionist_1.shtml.

9Rebecca T. Alpert, “Reconstructionist Judaism in the United States,” in the online version of Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, on the Jewish Women’s Archive website, http://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/reconstructionist-judaism-in-united-states.