In his paper, my colleague Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen addresses what he calls “the most prominent challenge the Christian church faces in the beginning of the third millennium,” which is the impact on daily life of “persistent plurality.” The use of the word “persistent,” which he borrowed from the document “Religious plurality and Christian self-understanding,” is worth underlining. I am not sure all Christians living in multi-religious contexts where Christianity was historically dominant have come to terms with the fact that their society has irreversibly changed, and that they must now turn to the Bible for resources on pluralistic contexts they may have overlooked in the past.

It may seem easier for some Christians to tolerate or advocate for a plural society as long as it is not in their backyard. In other words, from their perspective, foreign religions can be given a tourist visa but should not take residency; likewise, foreign countries should all make sure they protect Christians’ rights. Consider, for instance, the recent ban on the minarets in Switzerland and on full veiling in public in France and Belgium. When Islam was practiced silently behind closed doors, it did not seem to challenge churches as much as when Muslims made their faith public. Most churches in Europe have better learned to navigate the waters of secularism than those of plural religious societies.

At the same time, we should not ignore the apprehension and difficulties of those who daily share the same space with other religions. As they see other faiths around them flourish, they imagine a scenario similar to the one in which Christianity lost ground to Islam in the Middle East or North Africa over a millennium ago. They fear the worst for their own communities. A growing number of Christians I meet in European churches are now adopting the “eye for an eye” or “tooth for a tooth” approach. They refuse to accommodate the needs of believers from other religions as long as Christians in the countries they come from are restricted from the same privileges. The prospect of successful plurality grows tainted by feelings of fear and threat.

Therefore, I believe Kärkkäinen’s paper is a timely contribution to the much-needed conversation that should take place not just in seminaries but also in every place where Christians gather to pray and read the Word of God. I would add that although there are differences in the way plurality is managed around the world, those who have recently been exposed to it should learn from churches in places like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Lebanon, who have lived for centuries in pluralistic societies. And as Kärkkäinen points out, instead of looking only at social, cultural and political challenges, Christians must not forget the theological challenges and resources these churches have to offer.

Exclusivists, one of the three categories of Christians that Kärkkäinen describes in his paper, may find a pluralistic world a greater challenge because of the conflicts and divisions that arise from the differences they see between them and the religious Other. Does this mean that the world would be easier to share with inclusivists or pluralists? It would certainly harbor less polemics and fewer theologically fueled conflicts, and other faiths may feel more welcomed. Some readers may conclude that convincing exclusivists to abandon their views would be a quick fix for interfaith relations. I instead suggest that exclusivists be allowed to keep their convictions but be encouraged to put greater effort towards relationship building with people from other faiths, and adjust their attitudes when those drift away from biblical principles due to the fierceness of debates and polemics.

Kärkkäinen’s paper provides a number of good suggestions to help exclusivists, and others, to improve, if necessary, their skills in “othering,” “hospitality,” and “holistic understanding” of mission. Exclusivists will certainly welcome his exhortations to love their neighbors. But in their case, since the problem is not the neighbor so much as it is his/her religion, they should theologically explore how to manage the impact of religious differences on social relations. For example, those who believe their values are more excellent than those of other religions may have to reflect on the impact this has on the religious Other. Likewise, people who consider the religious Other saved only through a personal commitment to Christ must decide whether the latter are just candidates for conversion, or perhaps could become personal friends. Finally, if the neighbors of another faith do not accept Christ, are they automatically put in the category of the “forever-Other” from whom one has to stay away? Forgive my hyperbolic statements and broad generalizations. My sole intention here is to encourage mission-minded Christians, like me, to explore with greater diligence biblical resources that combine both witness and shalom in a pluralistic context.

Sometimes theologians and scholars who study people from other faiths find it easier to deal with these issues. Christian believers at the grassroots level may feel more vulnerable to the challenges of a pluralistic society because they rub shoulders with the religious other in day-to-day life, which is far different from academic exercises. Christians who live as a minority in their country or in their neighborhood may be inclined to think that theology of religions is less useful than solving daily social problems in their multi-religious contexts. Kärkkäinen’s paper, however, illustrates that it can be a great addition to whatever else is done. I would also add that it is useful as long as the theology addresses the concrete problems of believers at the grassroots level. They must gain a biblical understanding of how God sees other religions and be able to draw implications for their daily encounters with people from other faiths.

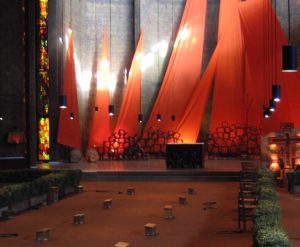

I noticed this gap between experts and laypeople when I was at the Festival of Sacred Music in Fes, Morocco, a few years ago. There were two kinds of events during the weeklong festival. One was for people with tickets who had some experience in crossing religious boundaries through art, and who listened graciously and often with much enthusiasm to music from different religions. The other was free and open to everyone and only music from one faith, in this case Islam, was played. The majority of the people at the grassroots level only attended the second event. The organizers may have been aware that without some preparation and education in interfaith relations, the process of “othering” through music cannot take place. This made me think of the local church, and how often we put high expectations on believers who fail to mix with people from other faiths in order to be salt and light. They may not be ready, like the crowds in Fes, to join the multi-religious concert; and yet, in most cases, they are forced to experience the plurality because of the transformation of our societies. How can we assist them at all levels of engagement? How can we provide them with a biblical foundation of interfaith relations?

It is not enough to equip grassroots exclusivists with information and practical tools to proclaim the gospel to people from other faiths. It is not enough to help them understand other religions better. It is not enough to encourage them to love their neighbors. All of this must be combined with a careful monitoring of the divide that their theological views and resulting actions creates between them and the religious Other. They must be able to differentiate between the unavoidable tensions that the proclamation of the gospel generates in interfaith relations and their potential misunderstandings of God’s perspective on other religions. It is here that theological reflection conducted at the grassroots level is most valuable.