As a Jewish Christian working on the interfaces between Christianity and Islam, the pastor thought I would be an ideal person to lead prayers as the congregation marked the anniversary of ‘9/11.’ I invited a Palestinian Muslim friend to join me—a brilliant doctoral student researching the media’s treatment of Jerusalem. Together, we went up to the front of the church, and I asked her, ‘What would you like me to pray for?’ I have never forgotten her answer. I had expected something sophisticated and political, but she simply said, ‘I’ve thought about this a lot. Just pray that everyone, on all sides, can have a safe place for their family and enough to eat.’ Together, we held hands and wept as I led the congregation in prayer.

The desire for a safe place for our people, with sufficient provision, lies deep in human nature, because God made us that way. He made human beings not singular but plural, to dwell together (Gen 1:27-28; 2:18-25). He put them in a land, and He gave them plenty to eat (Gen 2:15-16). But there is one more thing: He gave them dominion within that land (Gen 2:26, 28) so that a measure of taking control is also part of human nature. Of course, back there in Eden, the first human beings understood that it was God who was in ultimate control. Their own dominion was their God-given responsibility, to be understood as caring for His creation at His command. But it was not long before they decided that they wanted more; they wanted to be something even greater than the image of God, to take some of His prerogatives, and so they lost their land and their security. From then on, we can trace battles for land and security through all of human history.

The Babel story is the peak of the Genesis 1-11 analysis of this aspect of the human condition. Clearly echoing the Babylonian creation stories and alluding to Babylonian empire,[i] Gen 11:1-4 describes a people who want to stay together and to make a name for themselves in their own land. It is what I have identified as a ‘dangerous triangle’ of people, power and land.[ii] In this case, it is so dangerous that God breaks up their project to limit their power. What makes it so dangerous? This is not only a political enterprise, but also a religious one. At the center is the tower seeking to reach heaven—an obvious picture of the Babylon temple, the home of the god Marduk. This is an amalgam of religion with regard to the people-land-power triangle.

In short, the good-creation-triangle, of people with responsibility in a land in the presence of God, has turned into a dangerous one—of people-power-land, propagated by religion which will characterize the fallen world. Azumah tells us that ‘Islam is not the problem:’ I want to ask, ‘What, then, is the problem?’ and, ‘How can asking questions about the problem lead us towards a solution?’ The above analysis suggests that there is an underlying question of how religion relates to people, land, and power.

A secular answer to this underlying question might be that religion should be kept right outside the triangle, and that political aspects of any religion are, therefore, deplorable. But what might be a Christian view? How might that differ from Islamic views? What is special about such Islamic views that undergird current violence? What is at the root of the rise of Boko Haram and ISIS in their particular places and at their particular times? And, for that matter, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Jama’at-i-Islami and the Taliban as well as the various other movements of the 20th and 21st centuries? Are these a single phenomenon, or do they have different roots? And, at this point in history, how do we understand not only the range of Islamic action but also the range of Christian and Western responses to that violence? What is and has been the role of Western powers, with their interests in their own peoples, laws and territories, in their development? I trust that other respondents will raise such historical and geo-political questions. As a theologian, I want to return to some underlying issues.

The people of Israel, with their king in the Holy Land, and with God’s presence in the tabernacle and in the temple, can be seen as God’s plan to re-establish the creation triangle in the midst of the peoples and powers and lands of the earth. God even commanded a violent judgement in order to place the people in the land (see Deut 7:1-5 and its outworking through the book of Joshua). Sadly, the model failed again and again as even this People of God repeatedly fell back into the Babel pattern.

It is important, then, that, rather than trying to establish a renewed version of people-land-power under God, Jesus the Messiah challenged all the categories of ethnicity, territoriality and politics as well as of the religion of his day. The New Testament writers grapple with the question of what this might mean as the Gospel goes into the non-Jewish world. How does the new community relate to the ethnicity of the old community, and to its rule of law, and to its land? And how does it relate to the non-Jewish empire of the time? I would answer that the key here is that the writers focus not on people, on power or on land, but on the key aspect of the creation triangle which was so often lost: on the presence of God. What the Messiah accomplished in dealing with sin opens the way for the coming of the holy presence of God’s Spirit into the lives of believers and believing communities. As He insisted, this sort of reign of God cannot and must not be built on violence (John 19:36).

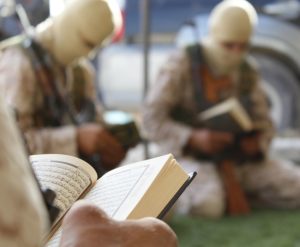

The founding Islamic model takes an opposite direction. The question of God’s presence is largely absent from the Qur’an, and this reflects the Qur’anic view of the nature of God.[iii] Rather, the key question is how human beings may receive and respond to God’s guidance. The people who accept the guidance which comes through Muhammad, then form a community which lives by laws derived from that guidance. From the beginning, the community needed to be established in a place–hence the move from Mecca to Medina, and the eventual conquest of Mecca. It was the process of establishment of the people with their leader and their laws which was the context for the famous founding battles of Islam. It was fitting, then, that the initial expansion of Islam was an expansion of territory which came under Islamic rule, and the conversion of the conquered people following very slowly after that.

Arguably the greatest challenge for Christians in today’s violent world is to ‘make sense’ of the Messiah’s choice in the midst of a fallen world which naturally uses religion to propagate the people-power-land triangle. In particular, how do we respond to the power dimensions which are written into the very foundations of Islam in a way which is appropriate to members of the Kingdom of God inaugurated by Jesus on the cross?

We could compare the trajectories of Christianity and of Islam throughout history, seeing how the different founding models played out. We would see both frequently taking an opposite pattern to their founders–that is, in non-political devotional Islam, and in Christian empire. Reflecting on Genesis 1-11, we might say that, since Muslims and Christians are human beings, all display aspects of the image of God as well as of the fall! The point, however, is that Islam has, from the beginning, been about spreading the rule of God through calling people to obey His law, that it required territory in its very foundation, and that it was legitimate to fight for that territory. Hence the wealth of material about warfare and governance in Islamic law that is noted by Azumah, as well as the material about violence in the Qur’an, Hadith and Sira, gives rise to the wide range of interpretation and misinterpretation explored in his paper. A goal of Islam may be a peaceful society, but, according to most interpretations, there is a place for warfare in the establishment of Islamic peace.

All human beings need a place to live, and it is natural to want one’s own group to be in charge, so Christians, too may fight for peace and for territory, but that is not what their Founder did. Too often, the fights for territory have been against Muslims; consider the crusades, the inquisitions, and the European colonial expansions which were so often accompanied by the expansion of the churches. Current Western militaristic violence in Muslim lands is perceived by many Muslims as ‘Christian’; and, at least in the US, there is a high level of evangelical Christian support for that violence. Too often, the fights for territory have been justified through Scripture with perhaps the most dramatic example, the equation between Joshua’s conquest of Jericho and the 1099 Jerusalem massacres in crusade literature.[iv] Some of the fights have been defensive rather than expansive, so we raise another key question: ‘How should Christians deal with legitimate human needs for people, power and land?’ This is not the place for developing a Christian theology of war and politics, but for emphasizing the urgency of such questions. These are not only questions about government and defense for particular nations, but about justice and righteousness for all of God’s creatures; in particular, it is about legitimate Muslim needs as well as about legitimate non-Muslim needs.

Many Western Christians are concerned about violence done in the name of Islam as a problem for Christians and for the non-Muslim world. One implication of Azumah’s paper is that there are huge problems within Muslim societies world-wide, and that we should be concerned about them not only for our own sakes, but also for the sake of Muslim people. Above, I raised the question of the roots of the various violent groups in today’s Islamic world: a broad answer is that all these movements arose in response to the problems experienced by Muslim societies during and after colonial rule.

What they have in common is that, whatever the problems, they see Islam as the answer. Why have things gone so wrong for Muslim communities? Could it be because they have not properly submitted to God? Do their people lack provisions? Surely God will provide for them if they follow His law correctly! What about ethnicity? On the one hand, Islam is often central to their ethnic identity: on the other hand, problems can be solved by seeing the Muslim Ummah as the key loyalty. What political model should they follow? When all the worldly options are so obviously failing, surely a return to Shari’ah and to the models of the Golden Age of Islam should be attempted. And what about land? Might it be that an Islamic view of all land as God’s land could cut the tangled Gordian knots produced by the ‘nation state’ divisions which cut across traditional ethnicity and territory?

That Muslims should see Islam as the answer is not surprising. Religious believers of all sorts believe that following their faith properly is the answer to their perceived problems. The Muslims cited by Azumah who oppose the violent movements, also see Islam as the answer—that is, they see their own interpretation of Islam as the corrective answer to the problems posed by the violent Jihadis. They are also likely to see Islam as the answer to other problems facing them and their societies.

Azumah reminds us of the ‘Golden Rule’ of the Messiah, Jesus, and leaves us wondering just how we are to apply it. How far should Christians align themselves with the many Muslims who see resources for peace within Islam? How much do we know about the history of Christian violence towards Muslims, and how far should we align ourselves with current politics which sees violence as a solution to violence? Can we begin to understand the problems for which such groups as ISIS and Boko Haram are trying to provide a solution? What might be effective just and compassionate responses to those problems? What part might we have in promoting those responses?

And can we offer an effective answer to the people in our Western contexts who might otherwise be drawn into violent jihad? To the disaffected boy who embraces Islam in a western prison as an escape from his addiction and criminality and/or a sublimation of his anger and violence? To the Muslim, whose response to the discrimination experienced by his family, is to declare war on the nation in which he grew up? To the youths who want a worthwhile cause to fight for? To a generation of Muslims who are trying to move from the popular and cultural religion of their parents to a 21st century faith? Do we really believe that the Gospel is the answer to both our own perceived problems and to theirs? Is the way of the Messiah sufficient?

Endnotes

[i][i] See, for example, G. Wenham, Genesis 1-15, Word Biblical Commentaries vol. 1, Waco: Word Books, 1987, pp234-246.

[ii] I. Glaser, The Bible and Other Faiths: what does the Lord require of us?, Downers Grove: IVP, 2005, chapter 7.

[iii] There is a difference here between the Qur’anic understanding of God as omniscient and omnipresent and the Biblical idea of the specific presence of God in theophanies, in glory, in the Messiah and in the Holy Spirit. See my Thinking Biblically about Islam, Langham, 2016. Note also that there are variant views within Islam, not least in various Sufi understandings of experience of the divine.

[iv] This is made explicit in Guibert of Nogent’s (1055-1124) Gesta Dei per francos. For a full exploration of how the Joshua conquest inspired this massacre, see C. Hofreiter, Making Sense of Old Testament Genocide: Christian interpretations of herem passages, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp 170-182.