Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies and God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God. For as we share abundantly in Christ’s sufferings, so through Christ we share abundantly in comfort too.

2 Corinthians 1:3–5

Some of the most profound dimensions of being human revolve around our experiences of suffering. We all suffer. No one lives without suffering. Our experiences may vary greatly: the degree or intensity of the difficulties, our internal or external capacities for sensitivity and endurance, the resilience and empathy of our family and community will all make enormous differences. At the very least, however, we know that nearly everyone does better in suffering if we have someone “suffering with” us—if we have compassion.

When the Apostle Paul reflects with unguarded candor on his own suffering in the opening of his second letter to the Corinthian church, he is doing far more than just describing his afflictions. He is theologizing with and pastoring the Corinthians, who face their own suffering. All of his afflictions, and theirs, are caught up in the suffering-with love of God who has suffered to comfort us, and who, in turn, calls us to comfort others in their pain.

We are not only those who “weep with those who weep,” of course. We also “rejoice with those who rejoice.” But it is definitely meant to be both. While all suffer, suffering does not automatically breed a readiness to suffer with others. This is where Paul lifts up the suffering of Jesus as the precursor that has touched the lives of all those in Corinth. We are to be motivated and enabled to suffer with others not just because we also suffer, but primarily because we who are in Christ know One who suffered with us and gave us comfort. This is the soil from which Christian compassion is explained and fortified.

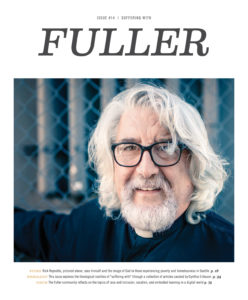

People ask me if I miss being a pastor. I understand the question, but it assumes difference more than similarity between being a president and being a pastor. I believe what mattered most to me personally about being a pastor is what still matters most to me about being a president: the privilege of standing with others in their stories of joy, of suffering, and of everything in between. These are the places where I most often see and experience the presence of God, and where I find the most grounded reminders of why the gospel, and why theological education, can matter so much. Sometimes because of being a president, and sometimes despite being one, I have the privilege of suffering with others. The suffering love of Jesus towards my suffering has stretched and opened my heart in compassion, certainly not because of my role or title, but because of my raw neediness that Jesus holds with tender, healing love.

It seems hard to look around at our world and not see suffering in every direction. When the plague devastated 14th-century Europe, it was often the Christians who most distinctively stayed in the cities to care for the dying—an instinct borne of knowing the God of all mercy and compassion. Whenever this has been the church’s reputation, the gospel has been authenticated. And when such love is not our reputation, or even worse, when it is the opposite, it is no wonder that our gospel is repudiated.

All who follow Jesus must ask: Have we been loved by God in our suffering? If so, then suffering with our suffering world is our vocation. God’s people can and must embrace and embody it, or we apparently have no good news.

Bendito sea el Dios y Padre de nuestro Señor Jesucristo, Padre de misericordias y Dios de toda consolación, el cual nos consuela en todas nuestras tribulaciones, para que podamos también nosotros consolar a los que están en cualquier tribulación, por medio de la consolación con que nosotros somos consolados por Dios. Así como abundan en nosotros las aflicciones de Cristo, así abunda también por el mismo Cristo nuestra consolación.

2 Corintios 1:3–5

Algunas de las dimensiones más profundas del ser humano giran alrededor de nuestras experiencias de sufrimiento. Todos y todas sufrimos. Nadie vive sin sufrimiento. Nuestras experiencias varían grandemente: el grado o intensidad de las dificultades, nuestras capacidades internas o externas de sensibilidad y perseverancia, la resistencia y empatía de nuestra familia y comunidad harán la gran diferencia. Al menos, sabemos que casi toda persona supera mejor el sufrimiento si tenemos a alguien “sufriendo con” nosotros—si tenemos compasión.

Cuando el Apóstol Pablo reflexiona con candor abierto sobre su propio sufrimiento en la apertura de su segunda carta a la iglesia de Corinto, está más que describiendo sus aflicciones. Él está teologizando y pastoreando a los corintios, quienes enfrentan su propio sufrimiento. Todas sus aflicciones, las de ellas y ellos, se ven enredadas dentro del sufriendo-con amor de Dios quien ha sufrido para consolarnos, y quien, además, nos llama a consolar a otros en su dolor.

Por supuesto que no somos solamente aquellos quienes “lloran con los que lloran”. También nos “regocijamos con quienes se regocijan.” Pero definitamente deben ser ambas cosas. Aunque todos sufren, el sufrimiento no nos dispone automáticamente a sufrir con otros. Es aquí en donde Pablo eleva el sufrimiento de Jesús como precursor de quien ha tocado la vida de todos y todas en Corinto. Debemos estar motivados y capacitados para sufrir con los demás no solo porque nosotros y nosotras sufrimos, pero primordialmente porque nosotros quienes estamos en Cristo conocemos a Aquel quien sufrió con nosotros y nos dió consolación. Esta es la tierra desde donde explicamos y fortalecemos la compasión cristiana.

Las personas me preguntan extraño ser pastor. Yo entiendo la pregunta, pero esta presume la diferencia más que similitud entre ser presidente y ser pastor. Yo creo que lo que más me importó personalmente siendo pastor es lo que todavía me importa siendo presidente: el privilegio de estar al lado de otros y otras en sus historias de gozo, de sufrimiento, y en todo el entremedio. Esos son los lugares donde veo y experimento con más frecuencia la presencia de Dios, y donde encuentro los recordatorios más fundamentados de por qué el evangelio, y por qué la educación teológica, importan tanto. Aveces por ser presidente, y aveces a pesar de serlo, tengo el privilegio de sufrir con los demás. El amor sufrido de Jesús hacia mi sufrimiento ha abierto y ampliado mi corazón en compasión, y no por mi rol ni mi título, sino por mi franca necesidad de que Jesús me sostiene con su amor tierno y sanador.

Es difícil no mirar alrededor del mundo y no ver el sufrimiento por todos lados. Cuando la plaga arrasó con la Europa del siglo catorce, con frecuencia eran las personas Cristianas quienes permanecían en las ciudades para cuidar de los moribundos- un instinto nacido del conocimiento del Dios de toda misericordia y compasión. Cuando la reputación de la iglesia ha sido ésta, se da validez al evangelio. Y cuando este amor no es nuestra reputación, o peor, cuando es lo opuesto, con mucha razón nuestro evangelio es repudiado.

Todos y todas quienes siguen a Jesús deben preguntarse: ¿Hemos sido amados por Dios en nuestro sufrimiento? Si es así, entonces nuestra vocación es sufrir con el mundo sufriente. El pueblo de Dios puede y debe abrazar y encarnarlo, y si no lo hacemos, es porque aparentemente no tenemos buenas nuevas.

찬송하리로다! 그는 우리 주 예수 그리스도의 하나님이시요, 자비의 아버지시요, 모든 위로의 하나님이시며, 우리의 모든 환난 중에서 우리를 위로하사 우리로 하여금 하나님께 받는 위로로써 모든 환난 중에 있는 자들을 능히 위로하게 하시는 이시로다. 그리스도의 고난이 우리에게 넘친 것 같이 우리가 받는 위로도 그리스도로 말미암아 넘치는도다.

고린도후서 1:3–5

인간 존재의 가장 심오한 특징들의 중심에는 고난의 경험이 있습니다. 인간은 모두 고난을 겪습니다. 고난 없이 사는 사람은 없습니다. 물론 사람마다 경험의 내용은 다릅니다. 곤경의 정도나 강도, 곤경을 느끼거나 견뎌내는 내적 및 외적 능력, 곤경으로부터의 회복력, 가족이나 공동체의 공감 등에 따라 실제 고난의 경험은 크게 달라집니다. 그런데 적어도 우리가 분명히 아는 사실은, 누군가 연민을 품고 ‘함께 고난 받는’ 이가 곁에 있을 때 거의 모든 사람이 고난을 더 잘 이겨낸다는 것입니다.

고린도 교회에 보낸 두 번째 편지의 첫머리에서 사도 바울이 자신의 고난에 대해 숨김 없이 털어놓는 것은 단순히 그의환난을 열거하는 것 이상의 큰 의미를 지닙니다. 바울은 현재 고난을 직면하고 있는 고린도 교인들을 목양하며, 함께 그 고난을 신학적으로 해석하고 있는 것입니다. 바울의 환난과 고린도 교인들의 환난은 모두 하나님의 ‘함께 고난 받는 사랑’ 안으로 녹아듭니다. 하나님은 우리를 위로하시려고 고난을 받으셨고, 이제 고통 가운데 있는 다른 이들을 위로하라고 우리를 부르고 계십니다.

물론 우리는 ‘우는 자들과 함께 울기’만 하는 사람들이 아닙니다. 우리는 또한 ‘즐거워하는 자들과 함께 즐거워’ 하기도 합니다. 분명한 사실은 두 가지 모두 우리의 모습이어야 한다는 것입니다. 모든 사람이 고난을 경험하지만, 그렇다고 다른 이들과 함께 고난 받으려는 마음이 자동적으로 길러지는 것은 아닙니다. 그래서 바울은 고린도의 모든 성도들이 삶에서 이미 경험한 예수님의 고난을 높이 들어 표상으로 제시합니다. 다른 이들과 함께 고난 받을 마음과 능력이 우리에게 생기는 것은 단지 모든 사람이 고난을 겪기 때문이 아니라, 바로 그리스도 안에서 우리는 우리와 함께 고난 받으셨고 우리를 위로하신 그 분을 알기 때문입니다. 바로 이 토양 위에서 ‘기독교인의 연민’을 정의하고 함양해야 합니다.

사람들은 제게 목사였을 때가 그립지 않냐고 묻습니다. 무슨 질문인지 잘 알지만, 질문의 이면에는 총장직과 목사직 사이에 유사점보다는 차이점이 클 것이라는 전제가 깔려있습니다. 제가 생각하기에 목사로서 제게 가장 중요했던 것이 총장으로서의 저에게도 여전히 가장 중요한데, 그것은 바로 다른 이들의 기쁨과 고난과 그 사이의 모든 경험을 곁에서 함께할 수 있는 특권입니다. 사람들 곁에 서 있을 때 저는 하나님의 임재를 보고 경험하는 경우가 가장 많으며, 더불어 왜 복음과 신학 교육이 그토록 중요한지 가장 실제적으로 깨닫게 됩니다. 때로는 총장이기 때문에, 때로는 총장임에도 불구하고, 저는 다른 이들의 고난에함께할 특권을 갖습니다. 그럴 때마다 예수님의 함께 고난 받으시는 사랑이 고난 가운데 있는 저를 품어주시며 제 마음을 열어주셨고 연민의 마음이 커지게 하셨습니다. 분명 이것은 저의 직책이나 역할 때문이 아니라, 적나라한 저의 궁핍함을 예수님께서 따뜻한 치유의 사랑으로 감싸주시기 때문일 것입니다.

세상을 둘러보면 어디든 고난이 없는 곳이 없습니다. 14세기 유럽을 전염병이 휩쓸었을 때, 남달리 도시 안에 남아서 죽어가는 병자를 돌보았던 사람들 중에 그리스도인이 유독 많았다고 합니다. 이는 자비와 긍휼이 풍성하신 하나님을 아는 데서 비롯된 본능적인 반응입니다. 역사 가운데 교회가 이런 평판을 얻는 곳이라면 어디에서든 복음이 진리임이 입증되었습니다. 반대로 우리가 그런 사랑을 보여주지 못하거나, 심한 경우 정 반대의 평판을 얻을 때, 당연하게도 사람들은 우리가 전하는 복음을 거부합니다.

세상을 둘러보면 어디든 고난이 없는 곳이 없습니다. 14세기 유럽을 전염병이 휩쓸었을 때, 남달리 도시 안에 남아서 죽어가는 병자를 돌보았던 사람들 중에 그리스도인이 유독 많았다고 합니다. 이는 자비와 긍휼이 풍성하신 하나님을 아는 데서 비롯된 본능적인 반응입니다. 역사 가운데 교회가 이런 평판을 얻는 곳이라면 어디에서든 복음이 진리임이 입증되었습니다. 반대로 우리가 그런 사랑을 보여주지 못하거나, 심한 경우 정 반대의 평판을 얻을 때, 당연하게도 사람들은 우리가 전하는 복음을 거부합니다.

예수님을 따르는 사람이라면 누구나 질문해야 합니다. 우리가 고난 가운데 있을 때 하나님은 우리를 사랑하셨는가? 만약 그러하다면, 우리의 소명은 고난 받는 이 세상과 함께 고난 받는 것입니다. 하나님의 백성이라면 그 소명을 품어야 하고 그것을 실체화시킬 수 있어야 합니다. 그렇지 않다면 우리에게 복된 소식이란 없습니다.