My most memorable experiences of interfaith dialogue came in the context of accompanying my husband, Inus Daneel, in his ministry among Indigenous Churches and Traditionalists in Zimbabwe. The 15-year civil war (1965–1980) and its aftermath were accompanied by massive deforestation, erosion, and the destruction of ecologically sensitive areas such as river beds. To combat this situation, in the early 1980s Inus allied with a group of chiefs and spirit mediums to launch what became ZIRRCON, the Zimbabwean Institute of Religious Research and Ecological Conservation. This groundbreaking ecumenical environmental movement among poor rural people in Masvingo Province aimed to reforest denuded communal lands and to teach sound ecological practices.

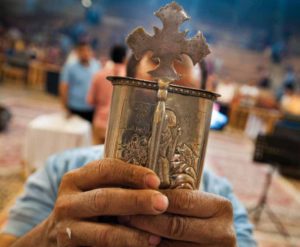

Among the remarkable aspects of the “War of the Trees” was its basis in religion. At its height, 180 African Indigenous Churches (AICs) representing an estimated two million people conducted joint tree-planting eucharists, in which participants confessed their sins against nature. After taking communion, church members planted seedlings and provided them follow-up care. The Traditionalist wing of ZIRRCON, on the other hand, was led by chiefs, war veterans, and spirit mediums who held beer libations and summoned the ancestors to protect newly planted seedlings.1 Over eighty women’s clubs conducted income-generating projects and activities for earth care, such as gully reclamation.2 Children’s groups held tree-planting days with the seedlings raised in our dozens of nurseries. Through the 1990s, ZIRRCON was the largest tree-planting movement in southern Africa. Together the Christian and Traditionalist wings of ZIRRCON planted hundreds of thousands of trees a year, before political upheaval destroyed the movement in the early 2000s.

My own position as wife of “Bishop Moses” gave me a bird’s eye view of practical interfaith activities.3 In addition to serving for several years as vice president of the board of trustees of ZIRRCON, I accompanied Inus to outdoor church services in which he functioned as a Ndaza Zionist bishop, dancing in a circle with the men and laying on hands to heal people. Later I conducted research among ZIRRCON-related senior women about their theologies.4 Probably my most important role was to support the theological education by extension program (TEE) that accompanied the Christian wing of the movement and that continued to exist for several years after its demise.

One of the most interesting aspects of my time with ZIRRCON was the long discussions Inus and I had about interfaith issues. As “amateurs de l’Evangile,”5 we lived in the tension between Acts 4:12 (“there is no other name under heaven given among mortals by which we must be saved”) and Acts 14:17 (“yet he has not left himself without a witness in doing good”).6 As a Christian, just how far should Inus go in participating in non-Christian religious rituals? He was the only white person to be admitted into the cave sanctuary of the Shona god in the Matopo Hills. He led delegations of ZIRRCON leaders to the oracular cave sessions for the high god to bless the movement. When interviewed about his knowledge of their religion and customs, leading chiefs indicated that he was a spirit medium who knew their ancestors.7 At the same time, Inus was a child of Dutch Reformed missionaries, scion of the famous missionary family of holiness spiritual writer Andrew Murray, and senior professor of missiology alongside David Bosch at the University of South Africa.8

The first condition of interfaith collaboration is the conviction that witnessing to the gospel required the mutuality of respecting persons whose understanding of culture, practices, and religion do not match one’s own. After a long history of colonial and racial oppression, AICs had firmly rejected white tutelage. Similarly, Traditionalist spirit mediums had led multiple uprisings against the white political regime. To work among them required a constant attitude of patient listening. Dialogue could occur only in the context of deep respect—and witness could occur only in the context of dialogue. Just as Jesus respected the woman at the well through establishing a relationship of mutual dialogue (John 4), despite their different religious traditions and genders, so Inus respected Traditionalist beliefs and practices. After attending oracular cave sessions as a respectful listener, he had earned the right to share the Good News of Jesus Christ. Following his attendance at high god rituals, Inus indicated that now it was his turn to share his own beliefs in Jesus Christ. He opened his Bible, read from the Scriptures, and testified to his belief in salvation through Christ. The sympathetic relationships established through respecting Shona religious rituals allowed for an ongoing contextually based witness to the gospel.

While mutuality was a precondition of interfaith dialogue, such a path was never easy. In 1993, a meeting of Christian and Traditional leaders was nearly derailed when the Traditionalist spirit mediums went into trances, and the Christian prophets began exorcising the evil spirits. Inus intervened in the mutual anathemas in order to save the movement. Traditional and Christian leaders agreed to hold joint ceremonies: Traditionalists sat and listened to Christian sermons, and Christians respectfully observed the beer libations. Following the different religious ceremonies, Traditionalists and Christians united to plant trees together. Interfaith action did not require capitulation to non-Christian beliefs. At beer libations, for example, all the Christians refused to drink the sacrificial beer that signified the summoning of the ancestors. Like his teacher the great Dutch missiologist J. H. Bavinck, Inus both saw God’s presence among non-Christian people and was sensitive to the “unmasking” of spiritual evil. Thus he appreciated but did not necessarily approve of everything in Traditional, or for that matter AIC, practices.

An added challenge for me was the need to navigate unbiblical and patriarchal gender roles and to relate to my counterparts in the movement, who were often wives ranked by hierarchy in plural marriages. Ultimately our task of missionary identification required that mutuality and respectful personal relationships be the foremost principle for interfaith dialogue. Common concern for God’s creation, for the “rains from heaven and fruitful seasons, and filling you with food and your hearts with joy” (Acts 14:17) remained a higher goal than imposing one’s own Christian beliefs on others— although witness always remained a happy privilege.

A fruitful text that characterizes evangelical principles of interfaith dialogue is Matthew 5:17: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill.” A century ago, “fulfillment theory” was a prominent theme in mission praxis. Missionaries argued that just as Jesus Christ fulfills but does not displace Jewish law, so he fulfills the deepest aspirations and most noble sentiments of other religions.9 The appeal of fulfillment theory to missionaries of the 1910s–1920s was that it provided an alternative to the failed negativity of colonialist displacement theory, which in its efforts to proclaim Jesus Christ had discarded the customs and worldview of indigenous people as so much useless garbage. Some Western missionaries argued that disdain for people’s customs, including their indigenous religions, shut off rather than opened pathways to Jesus Christ. Such insights by the 1930s merged into the discovery of mission anthropology.

Due to its overly optimistic and naive view of continuity between Christianity and other religions, fulfillment theory proved inadequate as a systematic missiology. However, I believe that at a practical level its insights continue to influence mission praxis. If Jesus Christ came to fulfill rather than to destroy, then it is not the task of the missionary to displace the customs of the people among whom he or she sojourns. It is Jesus Christ who embodies the mystery of salvation, not the missionary or transcultural agent. As a product of my own limited culture, I cannot dictate to other people what it means to follow Jesus Christ in all his fullness, in their own context. My task is to witness to transformation in Christ, but not to determine the terms of the encounter for persons of other cultural and religious backgrounds. Thus, while we fought for ZIRRCON to keep providing Bible study and TEE—against the secularist opposition of European development agencies that funded the movement!—interfaith earth care required mutual respect, continuous collaboration, and participation. The creative tension between personal faith in salvation through Jesus Christ, and the knowledge of God as Creator of the whole world, was maintained in the official key text of the tree-planting movement, Colossians 1:17: “He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” For lovers of the gospel, for amateurs de l’Evangile, earth care proceeds in the conviction that the God of salvation and of creation is one.

ENDNOTES

1See Marthinus L. Daneel, African Earthkeepers, vol. 1: Interfaith Mission in Earth-Care; and vol. 2: Environmental Mission and Liberation in Christian Perspective (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 1998, 1999); also see Daneel’s article on dissolution of the movement, “Zimbabwe’s Earthkeepers: When Green Warriors Enter the Valley of Shadows,” in Nature, Science, and Religion: Intersections Shaping Society and the Environment, ed. Catherine M. Tucker (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press, 2012), 191–212.

2See Sophie Chirongoma, “Karanga-Shona Rural Women’s Agency in Dressing Mother Earth: A Contribution Towards an Indigenous Eco-Feminist Theology,” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 142 (March 2006): 120–44.

3In the early 1990s, the Ndaza (Holy cord) Zionists made Inus a bishop. They named him “Moses” because he led them in theological education during the 15-year Zimbabwean liberation war and afterward into a ministry of earth care. Traditionalists called him Muchakata, or “wild cork tree.”

4Dana L. Robert, “Gender Roles and Recruitment in Southern African Churches, 1996–2001,” in Communities of Faith in Africa and the African Diaspora: In Honor of Dr. Tite Tiénou, ed. Casely B. Essamuah and David K Ngaruiya (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2014), 116–34.

5This early French term for “evangelical,” meaning “lovers of the gospel,” was proudly carried by my Swiss Protestant ancestors in the 1530s.

6NRSV used throughout

7“Interviews with Chiefs Chikwanda, Chivi and Murinye, ‘Muchakata and the War of the Trees,’” in Frontiers of African Christianity: Essays in Honour of Inus Daneel, ed. G. Cuthbertson, H. Pretorius, and D. Robert, African Initiatives in Christian Mission 8 (Pretoria: University of South Africa Press, 2003), 43–54.

8At Unisa, Bosch taught the A stream, Western theology; Daneel taught the B stream, African theology. Inus Daneel was thus the first professor of African theology and missiology at the University of South Africa.

9E.g. see J. N. Farquhar, The Crown of Hinduism (London: Oxford University Press, 1920); Kenneth Cracknell, Justice, Courtesy and Love: Theologians and Missionaries Encountering World Religions, 1846–1914 (London: Epworth Press, 1995); see also Edwin Smith, The Christian Mission in Africa: A Study Based on the Work of the International Conference at Le Zoute, Belgium, September 14th to 21st, 1926 (New York: International Missionary Council, 1926).