A Latin American Perspective

In the evangelical atmosphere in which I grew up in Peru in the 1950s, a distinctive mark of a bona fide Evangelical was that he or she did not believe in or practice dialogue. We were people with convictions that were to be proclaimed, not questioned or discussed. At that time there were two major religious persuasions in Peru: Roman Catholicism and Marxism. Yes, Marxism was embraced and practiced with religious fervor. Catholicism was more the official religion to which, according to the national census, 90 percent of Peruvians belonged.

When I entered college (1951–1957) I realized that not only were very few of my classmates practicing Catholics, many of them had become agnostics. Marxist students, on the other hand, were militant, always trying to win converts and ready to go to jail for their convictions.

And then a group of us evangelical students started to share the gospel on campus through Bible study groups, films, and lectures. I discovered that the best way to share my faith in public was dialogue. We brought speakers to campus—warning them that after their lecture they should be ready to answer questions. Some of them did not like the idea, but others did, and I myself developed a way of lecturing that would allow for questions. This dialogue after lectures was what attracted more students. Marxists would attend, and during the question time, they took the opportunity to preach short sermons on Marxism. Actually, the core and decisive points of my lectures were what I shared in responding to students’ questions. As time went on I became a staff member of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students in Peru, later in Argentina and Brazil.

I started to write my lectures about the Christian view of history, work, race, and social change. My colleague Pedro Arana published half a dozen of them in Peru in a book entitled Dialogue Between Christ and Marx. He included the most frequently asked questions by students and my responses. Ten thousand copies were sold during the “Evangelism in Depth” program in 1967, which resulted in the printing of a second edition. However, when the 1964 military coup in Brazil was followed by similar coups in Argentina (1966) and Chile (1973), those books had to be hidden or destroyed. Police or army officials who searched homes and schools looking for “communists” could not understand the subtleties of dialogue with Marxists. In that cold war atmosphere, there was no room for dialogue.

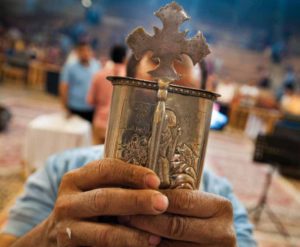

In Latin America where the Catholic Church felt threatened by the presence and work of evangelical missionaries, interfaith dialogue between Catholics and Protestants was unthinkable in the 1950s and 1960s. But then came Vatican II (1962–1965) with winds of change and renewal, including renewed attention by Catholics to Scripture. The Bible became a ground on which dialogue was possible. We were surprised to realize that there had been a biblical movement within the Catholic Church whose work became prominent with the Vatican II reforms. Dialogue became more frequent, and even Protestant Bible societies entered with Catholic publishers into common projects of translation and publication of the Bible. Thus dialogue was placed at the service of mission.

Between 1972 and 1975 I was General Director of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship of Canada, which has work among college and high school students. High school student groups needed a believing Christian teacher with a degree of conviction and commitment who could serve as an official sponsor. In some schools that had a student group, some Catholic teachers acted as sponsors, and I came to know and respect them. It was another form of dialogue for mission.

When I went to teach in the United States, I became a member of the American Society of Missiology (ASM), which was an enriching and formative experience. The ASM is made up of Conciliar Protestants, Roman Catholics, evangelicals, and Pentecostals, and its programs, publications, and governance are supposed to express this plurality. Thus, I came to know and respect many Roman Catholic missionaries and missiologists that were committed to Christian mission. I have a vivid memory of sharing meals in ASM meetings with Maryknoll women and men who had been missionaries in Latin America. They shared with me stories of their years of ministry, sometimes with tears in their eyes as they recalled the difficulties of serving and defending the poor and taking sides with them—a position that officially came to be known as the “preferential option for the poor.” Some of them had met evangelical missionaries and come to respect them in ways that the average Latin American bishop would not find acceptable. Thus together we explored the depths of our common Christian faith and came to respect one another and found that we could say that at our basic core, we had a common mission. I have to acknowledge that our common missionary background and activity gave us a kind of openness to dialogue that is far more difficult to find among the average parish priest or evangelical pastor in either Peru or the United States.

Through theological study and reflection, our convictions are formed, but historical awareness contributes to a deeper understanding of them, which in turn facilitate dialogue and enriches our fundamental perceptions. For instance, I still continue to explore the meaning of the following historical fact. The Protestant missionary movement is less than three centuries old. For centuries before the Moravian Pietists and William Carey, most Christian missionary work was carried out by the Roman Catholic orders. In spite of my Protestant suspicion of monasticism, I have much to learn from the centuries of mission history that preceded the Moravians and Carey. It would be naive to jump from the Apostle Paul to William Carey as some evangelicals seem to do.

The best document, in my opinion, that summarizes the findings of interfaith dialogue for mission is the report about the dialogue between Evangelicals and Roman Catholics (ERCDOM), edited by John Stott and Basil Meeking: The Evangelical-Roman Catholic Dialogue on Mission (1977–1984). In quintessential Stott-style theological precision, clarity, and even beauty we can see the points of agreement and disagreement reached during the seven years that the dialogue lasted. In the introduction to the document we find a description of the process of dialogue that serves as a helpful precedent.

Presently, after thirteen years in Spain, I have become aware of a serious deficiency in my missiological outlook. I must have a basic understanding of Islam if I am going to understand properly Spanish culture and Spanish Roman Catholicism. The eighthundred-year presence of Islam in Spain left a deep mark in all aspects of life, including agriculture, architecture, and industry, as well as religious attitudes and concepts about the role of institutionalized religion in society. Again in this regard, historical awareness is decisive. We cannot avoid the influence of our current bombardment by our Western media that creates stereotypes of Muslims and Islamic religion and culture that is unfair and simplistic. Though I have not taken part in any official academic dialogue with Muslims, I have had conversations with Muslim persons in different places, and I have often been intrigued, surprised, and humbled as I later reflected on those encounters.

I am now learning valuable lessons from Latin American missionaries in Islamic lands who take time to write and reflect about their experiences. One of them has written about the team’s first visit to the town where they intended to carry out evangelistic work. Their car broke down and they had to spend the night in town, and to their surprise, the local Muslims they had come to evangelize offered them hospitality, comfortable beds, and humbly shared their food. As a result, some of their preexisting stereotypes had to be abandoned, and in turn, new and unexpected ways of sharing Christ were to be imagined.

Interfaith dialogue at the academic level is one thing. It requires a respectful familiarity with texts from different faiths and a disposition to listen to one another. Historical awareness is also very important in the process as it represents an attempt to situate and correct contemporary popular media stereotypes. For example, realities such as globalization influence the way in which those who speak on behalf of the faith communities express their understanding of their faith.

On the other hand, missionary interaction at a grassroots level is a different thing. It is filled with moments in which God’s power manifests itself, sometimes in unexpected ways, in the daily life of people and local communities. To the degree to which missionaries are ready to listen to local people (in the same way in which Jesus did), and willing to follow the promptings of the Holy Spirit, their understanding of their own faith will grow and deepen as they find new, creative ways of responding to those questions, in word and deed. Good missiology, I believe, has to benefit from these two kinds of dialogue.