Although often seen as being in opposition, Christian mission and interreligious dialogue complement each other. Linking them requires moving beyond two stereotypes: First, that mission is a we-they activity; that is, mission involves Christians ministering to the foreigner and the strange culture, the other religion, the needy, and so forth. The second understands dialogue as an encounter that involves comparing differing views about the divine, usually with a stated openness to changing one’s own beliefs.

Understanding the complexity of Christian mission today can relieve us of the first stereotype. Besides traditional activities of service and preaching, Christian mission includes accompaniment, incarnational presence, working with the poor, and being ministered to by those a missionary serves. Even when Christians disagree about forms of mission, they can honor others’ ways and learn from them. My recent book, Graceful Evangelism, outlines seven forms of Christian mission and shows differences and overlapping motifs among them.1

Actually, mission is more like giving and receiving gifts than a one-way outreach to others. In Christianity Encountering World Religions, Terry Muck and I describe gift giving and receiving practices in different parts of the world.2 Cultures exhibit different ways of understanding gifts and therefore their giving and receiving practices also vary. We emphasize that Christian mission is a two-way street—receiving gifts from others and offering the priceless gift of salvation through Jesus Christ. “Giftive mission” thus becomes a metaphor for contemporary Christian mission.

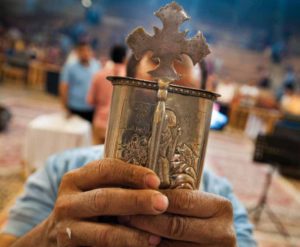

Interreligious engagement also mirrors the giving and receiving of Christian mission. It offers multifaceted ways of being with people of another religion. Formal interreligious dialogue about beliefs by proponents of different religions represents only one form of dialogue. It is an important forum that engenders deeper understanding of both theological nuances of different religions and varying beliefs within denominations and sects of a particular religion. Increasingly this form of dialogue seeks an honest encounter with others whose convictions are held as deeply as one’s own. Participants need not be open to changing their religion but must be clear about their own beliefs and open to listening and respecting the beliefs of others.

Moving away from those two stereotypes reveals many forms of engagement with persons and communities of religious difference. Some focus on theological conversation, some on project building, some on civic action, and some on friendship. One of the best ways to engage people of another religion is through friendship. It offers a kaleidoscope of experiences that expands understanding and fosters mutual respect. Friendship offers experiences of another religion that one cannot gain through academic study. It offers opportunity to witness to the gospel, to be Christ’s hands and feet for others. And it offers the chance to receive.

When I taught at Jakarta Theological Seminary in Indonesia, in the early 1990s, I chose to live in a Muslim neighborhood instead of on campus. Within a few days I had been introduced to the family next door. A mother and her twelve-year-old daughter appeared at my door with a sumptuous meal. “I see that you are living alone,” the woman said. “You have no mother here. I will be your mother.” Faithful to her word, Masooma turned up at my door at least once a week with a meal for me. She frequently invited me over for milk-tea in the afternoon. Sometimes I would sit nearby while she instructed a group of youngsters in reading the Qur’an in Arabic. I also got to know Masooma’s husband and daughters, aged twelve and seven.

After a few months, our appearance in the other’s house seemed natural. We spoke of our religions—how they overlapped, how they differed. One day Masooma scolded me for leaving my bible on the floor next to my low bed. “It is wrong to put the sacred book on the ground,” she admonished. I asked about the mosque and the fast during Ramadan. She requested the Christmas cards I received after the holidays. Masooma and her husband taught at the Pakistani International School in Jakarta. I taught at the Christian Seminary. Yet we found time in our busy schedules for friendship.

The girls especially liked sitting on my front stoop playing with my kitten, Bib. The Muslim idea of a pet’s “place” is outside. Masooma appreciated the wonder her children felt while playing with Bib, but she would never have a cat in her home. The kitten’s playful companionship was a gift that I could give. I too received gifts of hospitality—learning about their family life through visiting, observing religious practices, and sharing meals.

Another way to do interreligious engagement is through teaching and learning. Courses on mission, world religions, and social ethics provide opportunities for interreligious dialogue in the classroom while preparing students to encounter those of other religions in their daily life. The classroom context provides a forum for questioning one’s beliefs as well as learning from the beliefs and practices of others. In a course on world religions at Trinity College in Singapore in 2002, a student from a Hindu background became concerned about the foundations of her Christian faith. Was she a Christian because her mother believed in Christ and because she was alienated from her Hindu father? Her final paper, comparing Hinduism and Christianity, helped this student to better understand why she believed in Christ and how Hinduism provided religious meaning for her father.

Asbury Journal, published by Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, Kentucky, devoted an issue to teaching and learning practices that can be helpful to Christians teaching in an interreligious context.3 In that issue, professors shared the most meaningful practices that shaped their own teaching. Those salient experiences can provide tools to a teacher who is learning about other religions and respectfully engage students of other religions in one’s classes.

Travel offers another venue for linking mission and interreligious dialogue. As my husband and I hiked the Anna Purna Trail in Nepal in 2002, we met Westerners taking up the challenge of trekking and seeking knowledge of nature. Our Hindu guide Rishi had questions about Christianity. He shared with us his own Hindu practices and beliefs. We even met a Tibetan Lama who told us miraculous tales of sustenance on the trail given by his prayers and the prayer beads he offered to others.

New ways of practicing Christian mission and interreligious dialogue make this an exciting time to do both. Formal interreligious dialogue presents opportunities for deepening theological understandings of different religions. “Giftive” mission and informal theological conversations can expand interreligious engagement. Experiences of interreligious engagement through building friendships, teaching and learning in the classroom, and travel have enriched my own life as a scholar and a Christian.

ENDNOTES

1Frances S. Adeney, Graceful Evangelism: Christian Witness in a Complex World (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2010).

2Terry C. Muck and Frances S. Adeney, Christianity Encountering World Religions: The Practice of Mission in the Twenty-First Century (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009).