Evangelicals and Interfaith Dialogue

“Love your neighbor as yourself” is a pivotal command incumbent on all Christians. Moses established this teaching, and Jesus reinforced it, declaring that love of God and neighbor is the mega commandment for his followers (Lev 19:18; Mark 12:28–34).

Introduction1

Every concerned and culturally alert generation of Christians must keep asking, “Who is my neighbor?” There is a good possibility one’s neighbor may be a Jew or a Muslim, especially in the cities and suburbs. Next to Christianity, Judaism and Islam are the two largest world religions found in America. How many evangelicals Christians really know their neighbors, especially when they espouse a different faith tradition from their own? And how many Jews and Muslims have been sensitively encouraged to cross the “interfaith divide” so they may really know evangelical Christians? Is it not presumptuous for a Christian to claim he “loves his neighbors” when he has made little effort to know and understand those of different faith traditions living in his locale? Is it possible to fulfill Jesus’ command by choosing to remain largely aloof from one’s neighbor, and to remain uninformed about his religious beliefs and practices? Do Christians have an obligation to build bridges of understanding and dynamic engagement with those of other faiths? In heaven, will there be any credit for avoiding the other?

My conviction and experience is this: if Christians are to be known, they must also know. One cannot genuinely love another he does not know. To “know” is not to confront abruptly, then dismiss quickly. Knowing someone implies a process; it is not a “bump and run.” Indeed, to “know,” as I use this term in the context of interfaith relations, is to grow in understanding and appreciation of the other through respectful conversation and shared experiences that lead to mutual enrichment and trust. In this essay, I will explore some of the lessons I have learned from my own personal journey of more than forty years as an evangelical venturing into the world of interreligious conversation.

Search for Hebraic Roots

I was raised in a Christian home, attended a Christian high school, and graduated from an evangelical Christian college and seminary. Following seminary, my university training was in Semitic and Mediterranean Studies, the languages, history, and culture of the Bible world. I began my teaching career in the early 1960s at an evangelical Christian College in New England. At the time, I thought I understood the history of the Jewish people, biblical literature, and how it applied to life today. As I look back, however, I realize how shallow my understanding was, especially concerning biblical Judaism and the last two thousand years of Jewish history. In addition, I soon discovered that what was lacking in my own personal life was actually a rather ubiquitous Christian problem, one prevalent throughout the church.

One of the hallmarks of historic, classic Christianity is belief in Jesus as Messiah and Son of God. This point however has caused division and hostility between Christians and Jews for nearly two thousand years. It remains an impasse which, humanly speaking, only God himself can ultimately bridge.

The consequence of this Christian-Jewish impasse left many Christians believing that Jews have everything to learn from them, but Christians have little or nothing to learn from Jews. For centuries, many in the church were mainly taught to feel sorry for Jews because they had missed the boat, theologically speaking. In the Christian scheme, Jews were often viewed as objects to confront and win over to the Christian side for the sake of the “gospel.” Christians, on the other hand, typically saw themselves as having no ongoing need of Jews and Judaism. Such limited thinking doubtless influenced the general malaise, passivity, and indifference of Christians toward Jews at the time of the Holocaust. Thus, because the church tended to view Judaism as a defective and “incomplete” faith, Christian teachers largely refused to take Jews and Judaism all that seriously. Rather, for many, the church had replaced Israel; the church was the new and true people of God. Hence Judaism was basically viewed as a theological cadaver, an antiquated, legalistic religion, a mere springboard to Christianity. So, once Christianity was established, the importance of Jews and Judaism had every reason to fall off the Christian radar screen. I had, in general, inherited and been influenced by this view of Jews and Judaism.

During my first semester as a full-time college professor, I remember how frustrated I was. Students would ask me questions about Judaism and Jewish-Christian relations I could not intelligently answer. I was woefully unprepared because my Christian teachers had never given any serious attention to the Jewish roots of the Christian faith and to understanding the importance of postbiblical Judaism. I still remember many of those frustrating questions. Here are a few examples: If the Temple was destroyed in 70 C.E., and animal sacrifices ceased, how do Jews today seek atonement of sin? When Jews hold a Passover Seder today, why do Jews eat chicken or fish, rather than lamb? Why do traditional Jews usually prefer Tuesday for their wedding day? Why does a bridegroom smash a glass at a Jewish wedding? In the book of Genesis, if Jacob and Joseph were both embalmed, why are Jews today usually opposed to embalming the dead? What is the relation of Jewish ritual immersion to early Christian baptism? Paul was a Pharisaic Jew from the tribe of Benjamin and a student of the Jewish sage Gamaliel. If the Jew Paul held to the teaching of “original sin,” why do modern rabbis seem to oppose this teaching (cf. Phil 3:5; Acts 22:3; Rom 5:12–19)?

My frustration with the questions above, and others like them, soon started me on a search to help fill this yawning gap in my education. Before long, I came to conclude that most evangelical Christians tend to score quite high in their knowledge of Jews and Judaism from Abraham to Jesus; their knowledge is generally very low, however, in the same subject areas from Jesus to the present. Christians tend to have little understanding of how Judaism, from the end of the first century onward, began to be reformulated, resulting in a reinterpretation of many aspects of biblical Judaism. In the Christian community this ignorance and blind spot have led to naiveté, misunderstanding, and distortion of contemporary Judaism by Christians everywhere. Indeed, it has often resulted in painful caricatures and ignorant, gross violations of the Seventh Commandment: “You shall not give false testimony against your neighbor” (Exod 20:16).

Overcoming Fear and Learning to Listen

The first few years of college teaching, I became increasingly concerned with the question of why Christians seemed so indifferent and unconcerned about Christian-Jewish relations and the Hebraic roots of the church’s faith. To me, it just did not compute. The very foundation of the Christian faith came from the Jewish people. I could not understand, however, why so many Christians seemed to care less. The church’s Scriptures, its theology, ethics, spirituality, and its understanding of history, social justice, and worship all came from Israel. Indeed, Gentile believers were “grafted into Israel”; Paul warned them not to be arrogant or triumphal, for the root of the olive tree (Israel) supported them (Gentiles), not they, the root (Rom 11:18–20). In light of these life-changing gifts of the Jews, in my mind, the only acceptable attitude of Gentile believers toward Jews was one of indebtedness, thankfulness, and appreciation. The more I studied, however, I became convinced that one of the main reasons the Holocaust was allowed to happen is because anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism were allowed to fester in and around the church from the early Christian centuries to the twentieth century. The church had received its spiritual heritage from the Jews. Instead of esteeming that inheritance, the offspring had turned against the parent. I wondered why the church, a people who had received so much from the Jewish community, could be so seemingly insensitive and uncaring.

Early on, I came to realize the evangelical and Jewish communities really did not know each other. Evangelicals and Jews passed like ships in the night. For the most part, Jews feared evangelicals because Jews saw them mainly as heavy-handed proselytizers, a people who only knew how to confront Jews about where they had fallen short on theology in general and the Messiah in particular. Sadly, some Jews rather crassly described the evangelical mindset as having but one goal: the stealing of Jewish souls.

Since the 1950s, many Jews had become increasingly wary of the evangelical movement in American society, especially its alleged goal of “Christianizing” America. Few Jews, however, were actually experienced in personal dialogue with evangelical leadership, and so they largely lacked an appreciation for the diversity of the evangelical movement and its intellectual depth.

A major consequence of this lack of social interaction and friendship-building resulted in much stereotyping of evangelicals in very pejorative terms. I have heard Jews make a caricature of an evangelical as little more than a missionary seeking to “prey” on uninformed Jews. An evangelical-Jewish encounter was often viewed with trepidation because Jews feared it would be a one-way street and they resented the notion of being targeted. There had to be a better way. All profitable conversation involves listening to each other, seeking to understand each other, and learning from each other.

Often when Jews have encountered evangelicals, Jews have expressed fear and defensiveness, worrying some unpleasant confrontation would result. Interfaith events can result in genuine dialogue and an opportunity to develop positive friendships, or they can be distasteful and even repulsive experiences. But this is not an exclusive, one-way street. Occasionally, Jews have taken the offensive against evangelicals. Over the years, I have personally witnessed some expressions of hostility, challenge, and even outright belligerence on the part of Jews toward evangelicals. But either way, every situation I have witnessed has left me with the conviction that we must find a better way. We have to talk. There is such a thing as respectful conversation, not a war of words. We can learn to disagree without being disagreeable.

Evangelicals in the Synagogue

My first few years of college teaching had left me convinced that book knowledge about Jews and Judaism was not enough. If the knowledge gap was to be narrowed, there had to be personal, long-term interaction with the Jewish community. At first, I invited local rabbis to lecture in some of my classes. It helped to put an address and a face on things we were studying in class. Often these lectures were sponsored by the Jewish Chautauqua Society. For the most part, the lectures were very beneficial. But they did more than inform. The physical presence of a rabbi in class began to break down the communication barrier and mysterious wall that seemed to separate us. Students could ask questions of the rabbi in the familiarity and security of their own Christian classroom. Lasting friendships with the Jewish community began to be established. This form of education about Jews and Judaism posed a question for me that is still not resolved: the Jewish community is willing to sponsor its scholar-teachers to go into Christian institutions to teach on virtually any requested theme about Judaism and the “Jewish story.” Will the day ever come when the Christian community makes its scholars available to speak in the Jewish community—and at its own expense? Would the Jewish community ever be open to this, or is this stretching interfaith engagement too far?

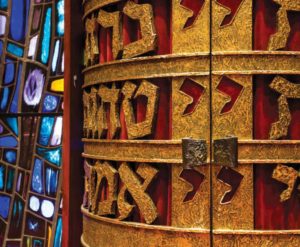

Within a few months, one of the Chautauqua-sponsored rabbis who had spoken several times to my classes, called me. He asked if I would be willing to read a section from the Torah (Deut 28) at his installation service at a nearby synagogue. I told him I would be honored to do so. It is always a privilege to read Scripture. The occasion proved to be joyful, yet sobering. The event began to open my eyes to the possibility of Christians learning from Jews and participating with Jews in the synagogue. I took a measure of encouragement from the observation of Martin Buber, the late Jewish biblical scholar: “We [Jews and Christians] share a Book, and that is no small thing.” I could see some real learning potential through on-site visits to synagogues. But I wondered how Jews would respond to a large group of non-Jewish visitors. I was curious to find out, so I decided I needed a course to be the vehicle for engaging in this type of off-campus learning.

The next fall I developed a new course. I called it Modern Jewish Culture, a title that has remained to this day. From the beginning, the course has proved to be a sort of potpourri on “Everything I wish I had been taught about Jews and Judaism, but was not.” Its main components, however, have included the beliefs and practices of Judaism, the Jewish roots of the Christian faith, and the history of Christian-Jewish relations. I want my students to be familiar with the similarities and differences between Judaism and Christianity, and also with why interfaith relations is important and how it is done. I was determined that learning must not be limited to textbooks and lectures. Students also had to learn from and interact with Jews in situ. To do so required field trips, a decision I am very glad I made.

To this day, I have made with my Christian students over four hundred, course-related field trips into the Jewish community. These visits have significantly shaped our perceptions of Jews and Judaism. We have visited worship services at Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Hasidic houses of worship. We have celebrated Jewish holidays, including Rosh Hashanah, Succot, Simchat Torah, Purim, Pesach, and Shavuot. We have attended Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Commemoration) gatherings, visited Jewish day schools, Jewish funeral homes, Jewish historical sites, and attended dozens of lectures and interfaith events at Jewish Community Centers. We have spent dozens of hours in local synagogues discussing Judaism and Christianity with rabbis, either before or after services. We continue to be graciously received.

Extending Hospitality in Worship

But do Jews feel as welcome and comfortable in evangelical churches as Christians typically do in most synagogues? From the Christian perspective, many churchgoers would quickly say, “Yes,” quite unaware of how de-Judaized the church has become over the centuries! From the Jewish perspective, however, Jews often feel like fish out of water. To be comfortable within a church is not an easy matter. Some Jewish leaders openly discourage visiting churches, or they express extreme caution about this idea. There are historical, theological, practical, and even symbolic reasons for this point of view. If Jews ever do enter a church, many Jews see themselves doing so only as “visitors,” or “observers,” never as “participants” of any service. In this modern society, marriages, funerals, and other rites of passage often bring Jews into churches. In addition, the high rate of intermarriage and the consequent expectations placed on the Jewish partner of an interfaith couple have increasingly brought many Jews within churches. Many separatistic, traditional Jews, however, tend to abide by at least two unwritten instructions concerning Christians: (1) never enter a church and (2) never discuss theology with a Christian.

In addition to the above restrictive guidelines, occasionally Orthodox Jews have been known to protest and to use physical force to ban their own from taking part in an interfaith event. This, of course is an expression of a very closed Judaism, unlike the more open modern Orthodox who have made certain adaptations to the realities of modern society. I will share one interfaith illustration from an experience I had with closed Orthodoxy. In the 1990s, I was invited to be one of the Christian speakers at an international interfaith conference at the Jerusalem Convention Center. Other Christian speakers on the program included the Archbishop of Canterbury and a Catholic cardinal from Germany named Joseph Ratzinger, a decade later elected pope, assuming the title Benedict XVI. Before the conference began, the Chief Rabbi of Israel appeared on television and told Israeli Jews to protest the event and to warn others not to attend. The Chief Rabbi’s position was that Jews were a majority religion in Israel, and so Jews had no reason meeting with or talking to those of another faith. The same day on which the archbishop, the cardinal, and I lectured, dozens of Orthodox Israeli Jews waged a sit-down protest, barricading the entrance to the hall of the Convention Center. I had never witnessed before in America this kind of protest of an interfaith event. I was glad when the Jerusalem police removed the protestors and allowed the conference to proceed.

Fortunately, not all Jews take the position that to enter a church, to meet with Christians in their house of worship, or even to meet in another neutral venue is to condone or put one’s approval on all the teachings and activities of the other. If that were the case in America, Christian-Jewish relations would not have made the enormous strides that it has since World War II, while many Jews are still somewhat tentative about entering the doors of a church to be present for a service of Christian worship. I have heard different responses from two rabbi friends of mine. I will briefly comment on each. The first rabbi, Orthodox in his identity, explains to me that he has no difficulty with certain aspects of the Christian worship service. For example, he says that from a Jewish theological perspective, there is not a line in the Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:9–13) with which he disagrees. He says, in principle, he could pray these words of Jewish origin with a group of Christians, but he chooses not to do so. According to this rabbi, the reason he will not pray the Lord’s Prayer is primarily symbolic. That is, it boils down mainly to a matter of outward, social Jewish identity. In the rabbi’s view, if he were to stand beside Christians in a church and pray a prayer coming from the Christian Gospels, this act could easily send the wrong message. So the rabbi chooses to abstain, even from the more “Jewish” parts of a Christian service.

Another rabbi, a friend whose view I also respect, is from the Conservative movement. He takes a different position. Personally, he is open to “selective participation” in church services. For example, this rabbi has told me of an evangelical church where he has a close relation with the pastor. The pastor and church members study Hebrew with the rabbi and sometimes join in services at his synagogue. The rabbi and his congregants are occasionally present at the church across the street. The rabbi states that he does this because he is sincerely open to learn from Christians, a point few rabbis will admit to—all the more so in public. In the rabbi’s words, “We Jews don’t know everything about God; we have a lot to learn from this church in town.” The rabbi further emphasizes, “These [Christian] people have a spontaneous expression of spirituality which is moving; their prayers are natural and from the heart, and their music is alive.”

Toward Refining Interfaith Conversation

Continued progress in interfaith relations cannot be taken for granted. There are still barriers to break down and there is yet much to learn about the other. As I have emphasized in this essay, if evangelicals are to be known, they must also make a sincere effort to know the other. No friendship could genuinely prosper if one partner were to impose his own way and insist, “It’s about me; come and learn solely about me; I am everything!” It does not work that way. Friendships are two-way streets. Friends value honest sharing. If a relationship is to grow and prosper, there has to be giving, not simply receiving. In interfaith relations, respectful conversation must replace confrontation; dynamic engagement replace strident badgering; and dialogue replace monologue.

From the time I first entered the world of interreligious dialogue, I have learned many valuable lessons through reading, listening, attentively watching, and personally participating. Accordingly, I offer a number of guidelines or rules of thumb for evangelicals to consider in order to move the dialogue to a greater maturity and productivity.

First, one must be committed to work on making gradual progress, with small steps, rather than quick giant strides. Often, it is more like being on a seemingly unending journey, rather than realizing one has suddenly arrived home. Evangelical-Jewish dialogue is a long-term venture. But it can be like a roller coaster; it has its ups and downs. Sometimes we take three steps forward and two backwards. Patience is required, for there is often a newness and strangeness to one’s dialogue partner and his faith orientation. It takes a commitment of time over many months—even years— to come to know the other and to build trust with the other.

There is no room for preemptive turf claiming here. “Love is patient” and “always perseveres” (cf. 1 Cor 13:4, 7). Inaccuracies and misperceptions of the other cannot be overcome overnight. After nearly two thousand years of considerable animosity, conflict, and avoidance, only in the decades after World War II have we begun to see some progress toward rapprochement between us. Therefore we must always be reminded that when Christians and Jews come together, history is on the table. Sadly, Christians especially carry a lot of baggage due to a long history of misunderstanding, hatred, and contempt.

My second guideline has to do with the style with which evangelicals conduct dialogue. Evangelicals must first commit themselves to listen, then speak. Listening is a godly virtue; some would even call it the ultimate form of humility. When the time comes to speak, evangelicals must always speak truth—as they personally have come to know and understand this—in love (Eph 4:15). There will be times when evangelicals and Jews disagree. When evangelicals disagree, they must learn to disagree sincerely, yet graciously. Such is a Spirit-filled art, not something that comes by intensive training from a debate coach. The style and demeanor of evangelicals should always be one of humility and modesty, especially regarding truth claims. Evangelicals understand that the truth they proclaim is already the truth that has sought them out. Thus, an evangelical’s attitude and posture is not one of triumphalism, assertiveness, showmanship, or arrogance. Rather, evangelicals speak as beggars telling other beggars where they have found bread.

A necessary prerequisite for effective dialogue is the willingness of evangelicals to learn from Jews. Thus, there is no place for pride, aggressiveness, or hubris. Evangelicals are servants, not masters. Evangelicals will seek no compromise on their theological nonnegotiables. But they must be committed to display integrity, uprightness, and the highest moral principles in their discussions. Evangelicals must learn to humbly submit their views for discussion at the dialogue table, not pontificate on them to others with a spirit of self-importance. Too often in centuries past, Christians have spoken for Jews rather than allowing Jews to speak for themselves. There is therefore a reticence and reserve required by Christians in dialogue. Indeed, Paul admonishes, “in humility consider others better than yourselves” (Phil 2:3). It is contradictory for people to say they have experienced grace yet not display graciousness; have experienced mercy yet be unmerciful and judgmental; have experienced love yet be unloving.

Third, evangelicals believe the Spirit of God is active everywhere. The Spirit primarily works relationally in the lives of people—guiding, teaching, comforting, empowering, and convicting them. The Spirit has a special redemptive role in the lives of believers. But God’s presence may also be discerned in the lives of others outside the church; God providentially works far beyond the categories theologians often confine him to. The so-called common grace of God is everywhere active in the world. If God can describe Nebuchadnezzar, a pagan king, as “my servant,” and Persian King Cyrus, “my anointed,” God indeed may be present and active in interfaith activities that are God-honoring. When caring for the poor and hungry, justice, righteousness, reconciliation, goodness, kindness, and peacemaking are displayed in this world, such may be potent signs of God’s presence and the manifestation of his will for humankind.

The starkness of a purely theological starting point for dialogue, if it fails to include also the relational dimensions emphasized in a more pneumatologically focused paradigm, is likely to minimize dynamic practical concern for the other. Unfortunately, exclusivism has often led to isolationism. God, to be sure, is at work in relationships. Theology is not simply propositional; it also has incarnational and dynamic dimensions. One’s partner in dialogue can be too quickly dismissed because he fails to measure up to the standard of the other’s theological yardstick.

In interfaith dialogue, however, when looking into the face of one’s partner, one may see the image of God (Gen 1:26). As divine image bearers, Christians and Jews remind us every human life has significance, dignity, and value to the Almighty. Though marred by sin and finiteness, each person reflects a divine likeness. Therefore, it is imperative that when evangelicals come to the dialogue table they show respect, honor, appropriate regard, and consideration for their dialogue partner. Agreement on everything is not necessary; a willing spirit is. We can sincerely believe others are wrong and still respect them, show unconditional love for them, and do good to them. The dialogue table is no place for the last word. Only God is absolute, and only he has the right to judge with finality and perfect knowledge.

There is a fourth guideline I wish to emphasize. Evangelicals must be reminded they presently know only “in part” (1 Cor 13:12). What cannot be fully harmonized or reconciled in this life must be left in the hands of the Ultimate Reconciler. In the meantime, these issues and tensions cannot be resolved by crusaders, jihadists, or political forces aimed at militantly furthering one people’s religious agenda at the expense of another’s. The diverse religious communities of any nation will have their disagreements among themselves and among other nations. In that vein, suicide bombing is never an acceptable expression of protest. Why? Every human being, right or wrong, has been created in God’s likeness. Whatever intentionally and randomly seeks to destroy innocent human lives defaces his creation and so diminishes the divine Presence in the world. The evangelical acknowledges a different type of conflict and a different means for conflict resolution. Ultimate resolution of conflict comes not by force or power but by the gentle persuasion and yielding of the human heart and will, voluntarily moved in submission to the Almighty. One’s “weapons” are not earthly, but of the realm of the Spirit (Zech 4:6; Eph 6:10–18).

My fifth observation is this: In seeking a better way through respectful conversation, evangelicals must realize they may often have to be satisfied with incomplete answers and partial agreement on various interfaith discussion points. In Scripture, truth is often indirectly or obliquely approached through the use of parables, analogies, or the answering of a question with another question. In certain evangelical circles there is an almost black-and-white approach to truth, a mindset that demands one must come to full agreement and closure on every issue now! In Jewish-Christian relations, as in the interpretation of a large part of Scripture itself, there will always be ambiguities, loose ends, and contrasting schools of thought. The differences between Christianity and Islam tend to be even greater due to Islam’s claim to a new revelation, the Qur’an, in the seventh century C.E. But if agreement on everything is a necessity for dialogue, then there can be no dialogue. The main prerequisite for dialogue is to come to the table with the right of self-definition and to grant that same right to others around the table. Depending on the agenda, this will lead to a mutual search for understanding and discovery of truth, wherever it lies. Though evangelicals first seek answers from biblical sources, they also acknowledge the importance of tradition, reason, and experience in working out the implications of their faith.

Evangelicals must acknowledge that a partial agreement on the discussion of what is truth and the will of God is better than total rejection of an entire system. There must be the ability to live with dialectical tensions, paradoxes, and incongruities. Dialogue will not work if one has to be right on every issue. One has to listen on every issue, and listen with a teachable spirit. Every human being must acknowledge they are fallible and far from omniscient. If the sole purpose of dialogue is to get an “opponent” to concede, rather than to see and understand, then dialogue is not dialogue. Only God has ultimate authority; no one has the power to compel belief. What one does with the discussion and evidence presented in dialogue is a very personal matter. A successful dialogue is respectful conversation, not relentless argument; a willingness to hear the depths of the pain of another, and be heard; the discovering that God loves honest questions and is pleased with those who seek answers.

Many evangelical critics of interreligious dialogue fear such a venture is really reductionism. That is, they claim such an encounter is aimed at reducing each faith to its lowest common denominator so a symbiotic, homogenized, generic religion will emerge. In my view, this is totally false and a misunderstanding of the word dialogue. This is not about relativism or theological capitulation. I and most other evangelical Christians I know are fully committed to historic Christian beliefs for specific reasons. Evangelical Christian identity is not a matter of physical birth but of scripturally born convictions. We are called to know what we believe and why we believe it. In evangelical Christianity, the preexistent Word, the deity of Jesus, his sinless life, atoning death, bodily resurrection, and second coming as King of Kings and Lord of Lords (see Rev 17:14; 19:16) are among the classic, central beliefs which distinguish Christianity among the Abrahamic faiths. And it will always be that way. A Christianity that becomes theologically diluted loses its distinctiveness and ceases to be an authentic expression of that faith.

To be known, one must first know. The twenty-first century will reveal if American evangelical Christians are willing to accept the current cultural challenge to reach out to further bridge the interfaith divide.

ENDNOTES

1This essay is an adaptation of the chapter “Christians Engaging Culture: A Better Way,” originally published in Mutual Treasure: Seeking Better Ways for Christians and Culture to Converse, ed. Harold Heie and Michael A. King (Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing, 2009), 125–43. Heie’s website, www.respectfulconversation.net, is devoted to modeling respectful conversation among those who disagree about contemporary divisive issues.