We have an image in our heads of what humanity used to be like – small, familial groups huddled together in the wilderness, living hand to mouth, spending our evenings around a fire for warmth and safety, spinning tales of gods who are as petty as we are but more powerful and more able to act out their desires. We had life but very little comprehension of it. We reached adulthood quickly. We had to. Our years were brief, and the only real difference between a child and an adult was physical. There was very little knowledge to learn, no paths one could take except for the path well-trod by your ancestors.

Girls were given in marriage at a very young age so they could bear children as soon as they were able, crossing a threshold into what the group considered womanhood. Lacking an obvious biological boundary between childhood and adulthood, boys participated in initiation rites centered on violence. Unlike women, men could not give life, but they excelled at taking it away, both from animals and from each other.

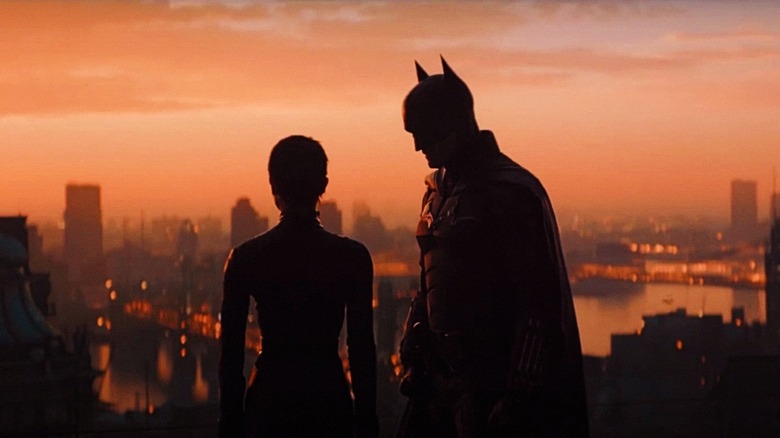

Judging by the movies currently playing in your local theater, those ancient narratives are still alive in our collective consciousness. The Worst Person in the World, an Oscar-nominated film from Norway’s stylish Joachim Trier, and The Batman, the latest incarnation of the cowled crusader, both wrestle with those old stories of girls becoming women only by giving life and boys becoming men only by taking it away. These two movies cry for new narratives, for new ways of reaching maturity that don’t depend on childrearing and violence, and for a balm besides being (dis)content to simply float through life.

The movies’ protagonists, a woman named Julie (Renate Reinsve) and Bruce Wayne (Robert Pattinson), ostensibly couldn’t be more different. She lives in the near perpetual sunshine of a northern summer – this is Oslo, after all. He lives in the near perpetual night of a noirish Gotham. She flits between career paths, relationships, and party scenes. He is single-minded in his obsession to save Gotham from itself. But these are simply the trappings of their environments and the movies’ genres. Underneath the booze and the bat suit, both Julie and Bruce are fundamentally the same. They are both early-thirty-somethings who hate who they have become in their efforts to distance themselves from the basic narratives society forces upon them.

She runs—literally and fantastically through the suspended streets of Oslo in the film’s stand-out sequence—away from any commitment that might lead her into a normal, stable life. Julie is another iteration of a kind of character that has been common since at least the days of Jane Austen. The contemporary version is urban, educated, and sexually adventurous. Civil rights and readily available contraception have freed her from the otherwise near inevitability of childrearing and the control of men and society. It is to Trier and Reinsve’s great credit that they have found a way to make her interesting once again.

The same could be said of Matt Reeves and Robert Pattinson. The Batman is less interesting than The Worst Person in the World, but, if you enjoy slight variations on the superhero theme, there is plenty to enjoy in The Batman. You’ll need to stomach the funk of it all though. The Batman is as violent as a scavenger ripping into a rotting carcass.

We have an image in our heads of what humanity used to be like – small, familial groups huddled together in the wilderness, living hand to mouth, spending our evenings around a fire for warmth and safety, spinning tales of gods who are as petty as we are but more powerful and more able to act out their desires. We had life but very little comprehension of it. We reached adulthood quickly. We had to. Our years were brief, and the only real difference between a child and an adult was physical. There was very little knowledge to learn, no paths one could take except for the path well-trod by your ancestors.

Girls were given in marriage at a very young age so they could bear children as soon as they were able, crossing a threshold into what the group considered womanhood. Lacking an obvious biological boundary between childhood and adulthood, boys participated in initiation rites centered on violence. Unlike women, men could not give life, but they excelled at taking it away, both from animals and from each other.

Judging by the movies currently playing in your local theater, those ancient narratives are still alive in our collective consciousness. The Worst Person in the World, an Oscar-nominated film from Norway’s stylish Joachim Trier, and The Batman, the latest incarnation of the cowled crusader, both wrestle with those old stories of girls becoming women only by giving life and boys becoming men only by taking it away. These two movies cry for new narratives, for new ways of reaching maturity that don’t depend on childrearing and violence, and for a balm besides being (dis)content to simply float through life.

The movies’ protagonists, a woman named Julie (Renate Reinsve) and Bruce Wayne (Robert Pattinson), ostensibly couldn’t be more different. She lives in the near perpetual sunshine of a northern summer – this is Oslo, after all. He lives in the near perpetual night of a noirish Gotham. She flits between career paths, relationships, and party scenes. He is single-minded in his obsession to save Gotham from itself. But these are simply the trappings of their environments and the movies’ genres. Underneath the booze and the bat suit, both Julie and Bruce are fundamentally the same. They are both early-thirty-somethings who hate who they have become in their efforts to distance themselves from the basic narratives society forces upon them.

She runs—literally and fantastically through the suspended streets of Oslo in the film’s stand-out sequence—away from any commitment that might lead her into a normal, stable life. Julie is another iteration of a kind of character that has been common since at least the days of Jane Austen. The contemporary version is urban, educated, and sexually adventurous. Civil rights and readily available contraception have freed her from the otherwise near inevitability of childrearing and the control of men and society. It is to Trier and Reinsve’s great credit that they have found a way to make her interesting once again.

The same could be said of Matt Reeves and Robert Pattinson. The Batman is less interesting than The Worst Person in the World, but, if you enjoy slight variations on the superhero theme, there is plenty to enjoy in The Batman. You’ll need to stomach the funk of it all though. The Batman is as violent as a scavenger ripping into a rotting carcass.

Bruce can’t escape violence—this is Gotham, after all—so where Julie runs, Bruce leaps (again, literally) into the combat zone. He dons a mask and bulletproof suit to buffer himself from the filth. I love how Reeves and Pattinson depict Bruce Wayne as a frightened, confused boy whenever he’s not wearing his disguise instead of as “secretly Batman” as in all other instances of the character. Both Bruce and Julie refuse to own up to their fears, to accept what they’ve inherited from their parents, and to get involved in something real.

Julie and Batman are like the campfire gods of old. They’re like us, driven by the same insecurities and desires. They just have more ability to do something about them. They can assume new identities, stop time, take any punch, dance around discomfort, expand their minds, and be more honest than others, though, notably, only when they are shrouded in anonymity. It is cathartic to watch the gods, to live vicariously through them. We don’t want to be them. They’re eternal but unhappy. We just want to learn from them and to be content in our simple, mortal lives.

It is tempting to think if only Julie could accept marriage and motherhood she would be happy like a princess or like one of her matriarchs, a notion The Worst Person in the World slyly undercuts. It’s tempting to think if only Bruce could hang up his batarang and stay home curled up with Catwoman, he’d find peace, having proven once and for all his adeptness at violence like the mythic warriors of old, be they caveman, niksum, hoplite, centurion, hoard, knight, viking, gallowglass, samurai, cowboy, soldier, or superhero – that the story is always the same should make us suspicious of it.

Nah. That’s never worked. If that was true, humanity would have found peace on earth long ago. The endings to both these films may feel a shade unresolved, but at least they do not tell a lie. Every superhero movie sets up a sequel. Stories like Julie’s usually end conventionally. The Worst Person in the World side-steps convention. In the moment, I didn’t like that it gives her an out, but I appreciate that it doesn’t force a resolution on a character who isn’t yet resolved.

Nope. We need something else. We need new narratives for how girls become women and boys become men, because the inadequacies of the narratives we’ve been repeating since we gathered around the campfires are manifold and obvious. The Bible does offer a different vision of maturity to anyone who identifies with its company of barren and marginalized women and men, who, even when they succeed at violence, reap the whirlwind. It’s a vision that welcomes women as fully empowered members of the community regardless of their marital or maternal state. It’s a vision of manliness marked by persistent stewardship and resilient grace.

We haven’t often wanted to read that story, not even those of us who claim the good book as our own. We’ve most often tried to shape God’s narrative to play well around the campfire, to frame “biblical manhood and womanhood” as something that looks exactly like what we already are. It’s easier that way. It requires nothing of us. It preserves the status quo. It lets us stay put instead of setting off in search of that better world. That’s probably why Julie and Bruce are so compelling. They may not have answers, but they don’t settle for less than that which their hearts long for. They pull us away from the fires of our ancestors and out into the unknown where I am convinced we will only find God.

Elijah Davidson is Co-Director of Brehm Film and Senior Film Critic. Find more of his work at elijahdavidson.com.