Nobody knows why the allies fire-bombed Dresden in the Second World War. Nobody knows why there are wars in the first place. The bombings happened in 1945, and a young Kurt Vonnegut lived through them as a prisoner of war. For 24 years, Vonnegut tried to write his “famous book about Dresden,” but was unable to get it right, because as he himself put it, “there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre.” Slaughterhouse Five, his final attempt to put something intelligent down about said massacre winded up rocketing him to fame and fortune, but not without the obligatory years of toiling as a veritable starving artist. In typical self−effacing style, Vonnegut the novelist tells you and I, the readers, right there on page twenty-five of the novel, that his book about Dresden, the most objectively successful work in his repertoire, “is a failure.”

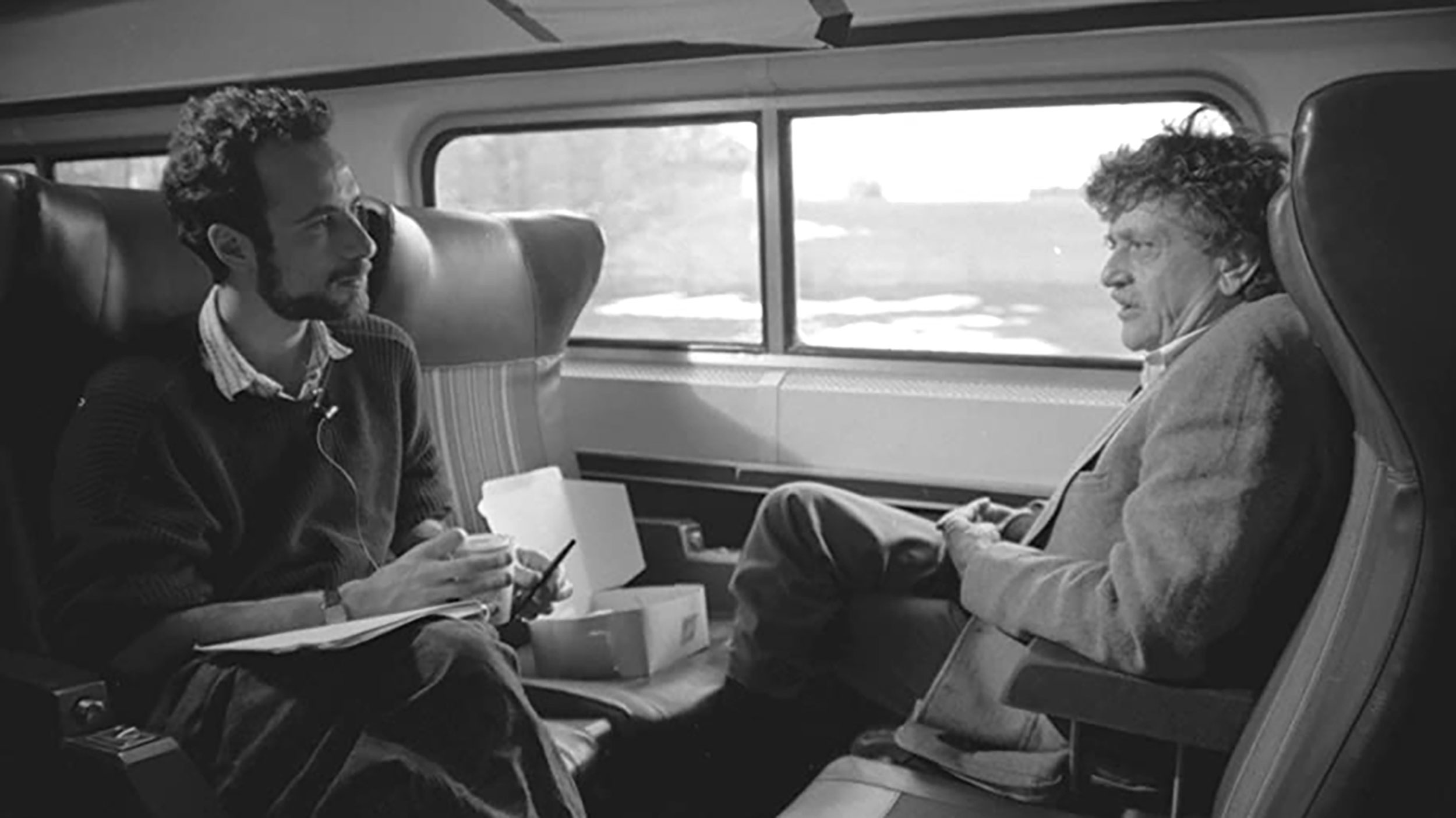

Perhaps Director Robert B. Weide’s documentary Unstuck in Time is a failure in the same way, insofar as it took almost 40 years to complete, and the enigma of Vonnegut the man, the author, and the artist seemed to stump Weide just as the experience of Dresden stumped Vonnegut. But of course, it is that failure which finally makes it such a great success.

Maybe it takes time for those big, wide, and deep thoughts to marinate, or maybe it takes time for the idea that there can be intelligible answers to things like this to fade away before any real profundity can be reached. In the end, Weide decided to include himself in the film, in part to provide an explanation for why the project took so long to complete, which seems to be the same strategy Vonnegut decided to take in Slaughterhouse Five, inserting his own voice in the novel as a mechanism for exposing the reader to his own mental wrestling match with the enigmas.

“So it goes,” became the phrase that he’d use after any particularly puzzling anecdote of tragic absurdity in the book, as a kind of resignation to the unsolvable problem of evil. And yet, we might be tempted to use the phrase here in a positive sense, as evidenced by the following.

So why did the film take so long? According to Weide, it was simply the fact that life, career, family and so on continually seemed to preclude the opportunity to properly finish the film, and all the while the excuse of the film provided myriad opportunities for Weide to spend time with his hero, who gradually became a confidant and finally a dear friend.

The result is that Unstuck in Time the film is part biopic, part buddy picture, and part point of view. Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut’s character who became “unstuck in time” and was abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore in Slaughterhouse Five, learned from these aliens that when someone dies, he or she is still very much alive in the past. This, in Vonnegut’s case, is absolutely true, and the film becomes a powerful testament to that fact, serving as a locus for a posthumous celebration of Vonnegut on multiple levels: as a novelist, writer, and public intellectual, but also as a friend, a father, humorist, aficionado of life, and finally a loved one.

So it goes.

Nobody knows why the allies fire-bombed Dresden in the Second World War. Nobody knows why there are wars in the first place. The bombings happened in 1945, and a young Kurt Vonnegut lived through them as a prisoner of war. For 24 years, Vonnegut tried to write his “famous book about Dresden,” but was unable to get it right, because as he himself put it, “there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre.” Slaughterhouse Five, his final attempt to put something intelligent down about said massacre winded up rocketing him to fame and fortune, but not without the obligatory years of toiling as a veritable starving artist. In typical self−effacing style, Vonnegut the novelist tells you and I, the readers, right there on page twenty-five of the novel, that his book about Dresden, the most objectively successful work in his repertoire, “is a failure.”

Perhaps Director Robert B. Weide’s documentary Unstuck in Time is a failure in the same way, insofar as it took almost 40 years to complete, and the enigma of Vonnegut the man, the author, and the artist seemed to stump Weide just as the experience of Dresden stumped Vonnegut. But of course, it is that failure which finally makes it such a great success.

Maybe it takes time for those big, wide, and deep thoughts to marinate, or maybe it takes time for the idea that there can be intelligible answers to things like this to fade away before any real profundity can be reached. In the end, Weide decided to include himself in the film, in part to provide an explanation for why the project took so long to complete, which seems to be the same strategy Vonnegut decided to take in Slaughterhouse Five, inserting his own voice in the novel as a mechanism for exposing the reader to his own mental wrestling match with the enigmas.

“So it goes,” became the phrase that he’d use after any particularly puzzling anecdote of tragic absurdity in the book, as a kind of resignation to the unsolvable problem of evil. And yet, we might be tempted to use the phrase here in a positive sense, as evidenced by the following.

So why did the film take so long? According to Weide, it was simply the fact that life, career, family and so on continually seemed to preclude the opportunity to properly finish the film, and all the while the excuse of the film provided myriad opportunities for Weide to spend time with his hero, who gradually became a confidant and finally a dear friend.

The result is that Unstuck in Time the film is part biopic, part buddy picture, and part point of view. Billy Pilgrim, Vonnegut’s character who became “unstuck in time” and was abducted by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore in Slaughterhouse Five, learned from these aliens that when someone dies, he or she is still very much alive in the past. This, in Vonnegut’s case, is absolutely true, and the film becomes a powerful testament to that fact, serving as a locus for a posthumous celebration of Vonnegut on multiple levels: as a novelist, writer, and public intellectual, but also as a friend, a father, humorist, aficionado of life, and finally a loved one.

So it goes.

Justin Wells is a documentary filmmaker and author. Find more of his work at justinwellsfilms.com.

In How to Film Truth, Justin Wells explores the history of documentary filmmaking as a search for truth by filmmakers, and a journey of discovery for subjects and audiences.