Engaging the Children of Anowa, Sarah, and Hagar

This essay argues that not only is interfaith engagement an invaluable form of Christian mission wherever Christian and other faith communities live together and share common social and geographical space, but it is also perhaps one of the most valued forms of Christian mission operable within dynamic multireligious urban contexts in North America.

What follows is an overview of the Interdenominational Theological Center’s (ITC) work to equip theological students for ministry in the dynamically religious contexts of urban USA. ITC’s unique approach toward interfaith competence supports and offers current and future Christian leaders opportunities for engaging three religions—African, Jewish, and Islamic— and their faith systems based on a more relational model of interfaith engagement.

Context

Located approximately five minutes from the Interdenominational Theological Center (ITC) in southwest Atlanta, Georgia, is the West End, a multiethnic, multicultural, and multireligious community that often serves as a dynamic living classroom without walls for courses in missiology, evangelism, and religions of the world. It is often acknowledged that the defining characteristic of West End is its wide array of religious institutions, from the historic West Hunter Street Baptist Church to an old-fashioned spiritual reader to the Shrine of the Black Madonna Cultural Center and Bookstore of the Pan-African Orthodox Christian Church. For at least 15 years, the West End community has played a significant role in providing ITC students with a dynamic learning context to discover and practice what it means to be a Christian leader with interfaith competence in a religiously dynamic community. Students engage the following religious faith communities:

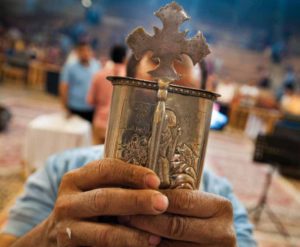

- The Children of Anowa (African Indigenous Believers): Anowa is a mythical woman representing Africa and the continental values of “love and respect for life, of people and of nature.”1

- The Children of Sarah (Judaism): The African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem, sometimes referred to as the Hebrew Israelites, or the Black Jews, are very active in urban cities of the United States.

- The Children of Sarah (Christian): Diverse Christian congregations have had a long and active presence in the West End.

- The Children of Hagar (Islam): The West End Islamic center, known as the Community Masjid, has functioned for more than 25 years, dedicated to the establishment of Islam in the West.

A key component of ITC’s theological education is developing an intercultural competence among students that is holistic, multidisciplinary and integrated, and honors missiology with a bifocal concern for both mission as evangelism and mission as dialogue with religions of the world.

The Methodological Components of an Interfaith Engagement as Theological Praxis of Christian Mission2

Recognizing that there is no religion that has not been influenced by culture and no culture that has not been influenced by religions, theological institutions should actively and effectively prepare students to engage in intercultural and interfaith ministries, identifying and utilizing key resources (sacred Scripture, tradition, culture, and social change) that have served to promote the Christian faith as an intelligent inquiry into God consciousness. This is crucial if Christian mission is to be perceived as useful and necessary by those living and working within the West End, as a heritage capable of embracing purposeful, creative, holistic, and healing human interactions. Because the contemporary struggle for human dignity and human rights within the United States is profoundly personal and communal, theological education has to take the first step in this recommended engagement of assisting local churches and their leaders in transforming their spiritual and theological resources in ways that ignite their sense of vision, purpose, and mission. Local churches situated in multireligious contexts need shepherding as they overcome ignorance, hesitancies, and the fear of change, and in providing a moral compass as they grow in their discovery of who they are and how powerful they can become without the need to demonize self or others who are different. Only when theological institutions can help churches and ministries embrace what church historian emeritus Gayraud Wilmore refers to as a “pragmatic spirituality”3—an active demonstration of the Christian faith—are leaders able to respond meaningfully, authentically, and faithfully to twenty-first-century realities facing African American communities.

This third circle involves bringing into focus the narrative of the theological education institution and its capacity to dialogue with the student who is engaged in interfaith activity for the purpose of shaping convictions, policy, and procedures. Defining and accessing demonstrations of effective implementation of Christian mission as interfaith engagement is not an easy task. Competence can be measured, but because interfaith competence involves more than knowledge of other religions, attention must be given to a larger and deeper educational process that involves the comprehension and development of one’s self and attitudes in effectively and successfully engaging with persons of diverse backgrounds.

Higher theological education institutions must begin by relying on their theological, historical, psychological, sociological, and creative resources as they seek to develop students with interfaith competence. There are six areas related to intercultural competence efforts that every institution of higher religious education must address:4

- Curriculum: What is taught, and how? The curriculum must address the broader goals of theological education: to form church leaders among God’s people, to inform them about their faith and its application to modern life; and to equip them to become agents of transformation in the churches and multireligious communities where God has placed them.

- Collaboration: Who are our partners? Emphasized is the need for various denominations, organizations, and community programs to work together in cooperation and genuine sharing as we recognize a common sense of mission and purpose for doing education for ministry.

- Confession (Spirituality): How do we celebrate and affirm the rich distinctive of our theological and ecclesiastical history? Spirituality speaks both to the personal and social dimensions of the student’s religious journeys.

- Contextualization: How do we imagine ourselves planted or situated in the context of our teaching ministry? The theology, curriculum, teaching methods, academic policies, and administrative structures are informed by the context of ministry and teaching.

- Constituency: This addresses the basic questions related to the students we are educating. It implies the “whole people of God” because it is the whole church that must witness to the whole gospel through word, deed, and lifestyle.

- Community: What relationships are important to our institution, our cultures, and the social and religious ethos? Certain religious persons and leaders of the West End have become important to our academic programs. Community implies educational cooperation with other existing organizations, social and educational, in our common life.

Because it is the mandate of theological institutions to not only guide but also accompany through education Christian clergy and lay leaders who seek the reign of God and desire to minister effectively in the rapidly changing, diverse, multiethnic, multicultural, and multireligious communities within the United States, these six categories related to the notion of interfaith engagement must be addressed.

The Overlapping, Integrating, Shaded Spaces of Reflection

The three circles I have presented are linked by shaded spaces that represent intentional, guided periods of theological reflection, sometimes in solitude, but most often communal. This is important in discovering the level of interfaith competency of the student as an anticipated outcome of theological education. Michael I. N. Dash, professor emeritus of the Ministry and Context Department, would stress again and again the importance of engaging in theological and ministry reflections that examine “one’s faith in the light of experience” and “experience in the light of one’s faith.” Aimed at pressing the question about the presence of God in the experiences of cross-cultural life and intercultural realities and the implications of that presence, Dash would utilize a four-source model of theological reflection that encourages attention to exploring the worlds of tradition, personal position, cultural beliefs and assumptions, and implications for action. It is through dynamic theological reflection on interfaith engagement that the student is lead to self-identify areas of personal responsibility and to take responsibility for personal growth and spiritual maturity as discerned necessary to accomplish a given purpose. Individual traits (flexibility, empathy, sincere listening, etc.) as well as attention to the nature of the relationship between individuals involved in an interfaith encounter are significant. Because there is no prescriptive set of individual characteristics or traits that guarantee compliance in all intercultural situations, relationships and the quality of relationships formed are also emphasized.

- Setting the stage: Who (define with specificity) is attending to this encounter, and what assumptions are undergirding the encounter?

- The story: What narrative is identified as a significant interfaith or interreligious learning incident?

- Reading the context: What contextual dynamics are at play, and how do you understand them?

- Rereading the sacred text: How might a refocus on the Bible as sacred text shed light on the particular story or narrated incident?

- New Mission or interfaith insights:5What new insight gained might help to shape a better outcome in light of integrated theological reflections?

- Mission action: What interfaith competence action is required as a sign and symbol of the reign of God?

- Retelling the story: How might a new ending result? As a result of engaging in this particular methodology aimed at discovering God’s will and God’s ways, how can we envision a different response, one that speaks of “love and respect for life, of people and of nature”?

Conclusion

As students prepare seven academic papers responding to the seven steps identified in the recommended methodology above, it becomes clear that through interfaith encounters, they serve the church in variety of ways: as public theologian, innovative faith leader, community activist, ecumenical global networker, creative educator, contextual communicator, prophetic social justice minister, and asset-based community developer. By suggesting a particular methodological paradigm, attention is given to how the interfaith engagement of students may become an analytical outcome of Christian mission that points toward a process that enables us to learn how to provide students with the attitudes, skills, and behaviors that will lead to effective, successful, and faithful leadership in contexts of religious diversity.

ENDNOTES

1See Daughters of Anowa: African Women and Patriarchy, by Mercy Amba Oduyoye (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1995), 10. Oduyoye further describes how Anowa is meaningful in the Ghanaian culture and makes references to other sources where Anowa is described as a priest (see Anowa [London: Harlow, 1970, and Longman-Drumbeat, 1980]) and a prophet (Two Thousand Seasons (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1973) who represents Africa.

2This methodology (and the related figures presented) is adapted from the work of an international research and writing team in which I participated, resulting in God So Loves the City: Seeking a Theology for Urban Mission, edited by Charles Van Engen and Jude Tiersma Watson (MARC, 1994).

3Pragmatic Spirituality: The Christian Faith through an Africentric Lens by Gayraud S. Wilmore (New York University Press, 2004) is the book referenced here.

4See Transforming the City: Reframing Education for Urban Ministry, by Eldin Villafane, Bruce Jackson, Robert Evans, and Alice Frazer Evans (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002). Although this work was originally presented as categories utilized in the academic subdiscipline of urban missiology, because of its commitment to people, the categories speak to key phenomena impacting intercultural and interfaith competence.

5Essential principles of womanist religious scholars, pastoral care givers, and womanist methodologies that are applicable and offer extremely helpful insights are as follows: the promotion of clear communication (verbal, physical and/or spiritual); multidialogical approach; liturgical intent that has implications for life and living; didactic intent that has implications for teaching and learning; commitment to both reason and experience; holistic accountability (rejects bifurcation between sacred and mundane); and a concern for healing.