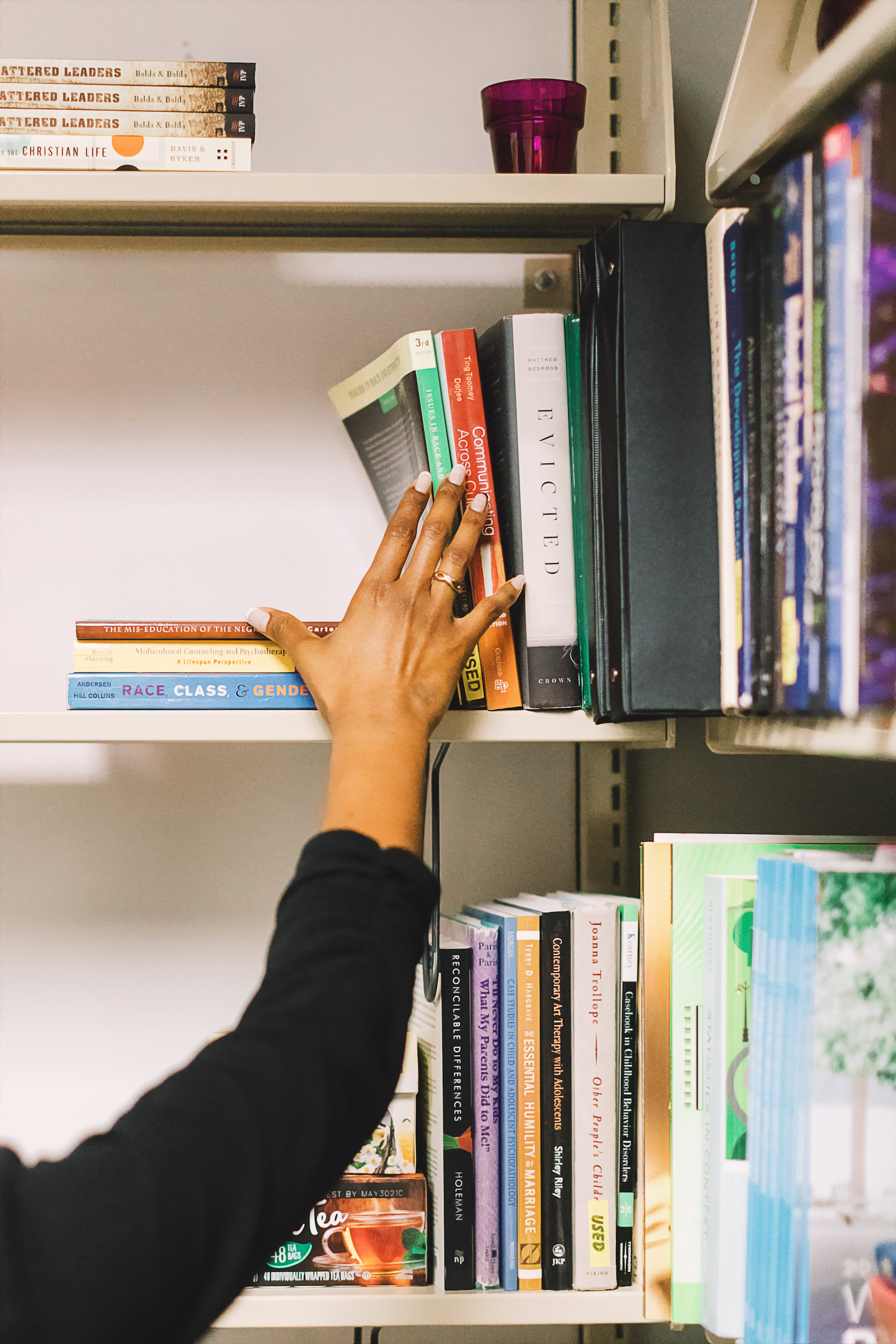

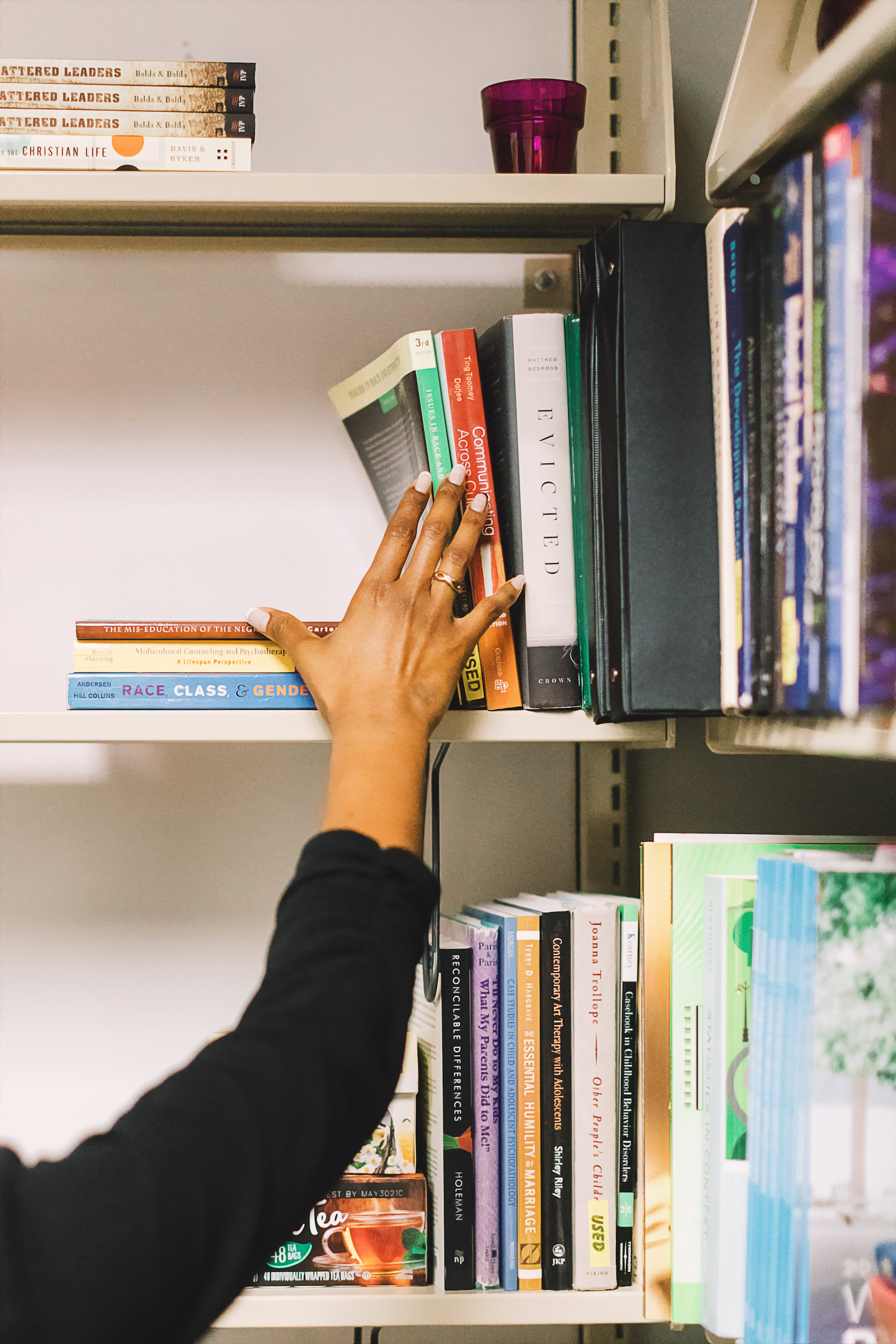

Christin Fort (MAT ’15, PhD Psych ’17) has always been interested in the intersections—those liminal spaces where one thing brushes up against another. As a Black woman in academia who focuses on both theology and psychology, she embodies these points of convergence in more ways than one.

When she puts her scholar hat on, Christin defines intersectionality as a theory that calls for a more holistic acknowledgment of the various factors that shape personal identity, as well as the “inextricable links” that enable these factors to impact one another. But when you ask her what this concept means to her personally, the answer is less ambiguous. “I like to do bridging work,” she says, “standing between two worlds.”

Like lowering a drawbridge, the more she connects to her own intersectional identities, the more fluid and traversable they become—for herself as well as others.

For example, she stands at the intersection between disciplines, with the integration of theology and clinical psychology being her academic specialty. “In my mind, integration is where you take a theological understanding of Scripture and of the person, and a psychological understanding of the person and of Scripture, and try to bring them together,” she says. While studying psychology as an undergrad at Wheaton College, where she now serves as assistant professor of psychology, Christin came to understand that her deep love of the subject was actually fueled by theological anthropology—or, in her words, “how we understand the person in light of what Scripture and theology teach us about human value and worth.” Upon graduating, she quickly realized there were few graduate schools out there that offered programs where she could pursue both disciplines in tandem.

Claire Mainprize (MAT ’20) is a freelance writer and editor based in Colorado’s Front Range. Find more of her work at ClaireMainprize.com.

Josh and Alexa Adams are a husband and wife photography team located in Wheaton, Illinois. Find their work at adamsphotography.co.

Christin Fort (MAT ’15, PhD Psych ’17) has always been interested in the intersections—those liminal spaces where one thing brushes up against another. As a Black woman in academia who focuses on both theology and psychology, she embodies these points of convergence in more ways than one.

When she puts her scholar hat on, Christin defines intersectionality as a theory that calls for a more holistic acknowledgment of the various factors that shape personal identity, as well as the “inextricable links” that enable these factors to impact one another. But when you ask her what this concept means to her personally, the answer is less ambiguous. “I like to do bridging work,” she says, “standing between two worlds.”

Like lowering a drawbridge, the more she connects to her own intersectional identities, the more fluid and traversable they become—for herself as well as others.

For example, she stands at the intersection between disciplines, with the integration of theology and clinical psychology being her academic specialty. “In my mind, integration is where you take a theological understanding of Scripture and of the person, and a psychological understanding of the person and of Scripture, and try to bring them together,” she says. While studying psychology as an undergrad at Wheaton College, where she now serves as assistant professor of psychology, Christin came to understand that her deep love of the subject was actually fueled by theological anthropology—or, in her words, “how we understand the person in light of what Scripture and theology teach us about human value and worth.” Upon graduating, she quickly realized there were few graduate schools out there that offered programs where she could pursue both disciplines in tandem.

Claire Mainprize (MAT ’20) is a freelance writer and editor based in Colorado’s Front Range. Find more of her work at ClaireMainprize.com.

Josh and Alexa Adams are a husband and wife photography team located in Wheaton, Illinois. Find their work at adamsphotography.co.

“Fuller led me to a place where I can say, ‘Here’s the person, and here’s Scripture, and you as a Black woman can use your perspective and bring that series of intersectional approaches to the text intentionally,’ and that wasn’t something I saw everywhere,” she says.

When it came time to choose her dissertation committee, Fuller’s emphasis on elevating intersectional perspectives became all the more evident. Her research advisor, Al Dueck, looked her square in the face and said, “Christin, you’ve already chosen two White men to be on your dissertation committee, and you only have three people. You need to go find a Black woman somewhere.”

Reflecting on that conversation, Christin says, “I loved having an old White male look at me and say, ‘Christin! Are you paying attention to who’s shaping you? Whose voices are in your head?’” But she was saddened to reply that there weren’t any Black women at Fuller—or anywhere, for that matter—who specialized in the specific interdisciplinary and integrative work she wanted to do.

“I wrestled with myself for a long time, wishing there were people who could mentor me within the topic that I want to be an expert in, and I don’t see them yet,” she says. “But my hope, and my prayer, is that God could help shape me to be one of those people, so that if someone else wants to study this, they can have someone—a woman and an African American of slave descent—who’s able to say, ‘Here’s my embodied perspective about this same topic that these other White men have studied but which I can bring my lived experience to.’”

Through her work as a co-director of Wheaton’s Multicultural Peace and Justice Collaborative (MultiPJC), Christin’s prayer is already being answered. As its website declares, “The Multicultural Peace and Justice Collaborative is not a typical research lab.” Instead, it’s a collaborative research team that is intentionally multicultural in membership and aims to understand its titular values from the inside out. That is, by not only studying and learning from other communities but actually creating a collaborative research and training community—one the members view as “an extended scholarly family/jiārén/famiglia/familia/ohana.”

Although John McConnell, the founder of this “scholarly family,” initially formed the MultiPJC as a regular social science research lab, he had hopes of making a space where the values he studied were embedded into its very fabric. So as Wheaton’s dean began hiring more ethnically diverse faculty, John promptly extended invitations. “He is very aware of being a White cisgender heterosexual male and wanted to use his privilege and power to elevate not only his students but also younger colleagues who are coming in,” Christin says. Now, there are four co-directors—each of whom comes from a different ethnic background and studies culture and race in their work—along with more than a dozen student members.

Christin’s own corner of the lab involves studying the various ways in which Black experience and faith intersect. She has one foot in each territory, often standing between the church, which she believes can often foster stigma surrounding mental health, and the Black community, in which “mental health access and resourcing are fraught with systemic challenges.” Things like unethical medical research, lack of access to culturally responsive mental health care, higher rates of serious mental health issues, and trauma. “A lot of my work as a Black professional psychologist

is to stand in the gap and say, ‘how can I be a bridge between my community that often has a healthy sense of skepticism of clinical professionals yet could also benefit from the resources that this profession has to offer?’”

A collaborative training project she’s currently working on with one of her doctoral students is focused on how the faith of African Americans inhibits or enhances social activism. Christin explains that some people come from a church tradition where those two things don’t necessarily go together. For others, they and their tradition say, “it’s because we love Jesus that we protest injustice.” Together, Christin and her research team seek to understand how one’s church tradition and ethnic background might intersect to either fuel them towards social engagement or prompt them to disengage altogether.

Two of Christin’s other MultiPJC students are doing qualitative work in which they interview clergy and psychologists working on the ground in Black church settings. They primarily want to know how such individuals are seeing mental health crises manifesting themselves in this setting, but they are also curious to know how their research participants are caring for their own mental health as well. In Christin’s experience, many Black clergy deal with traumatic situations that were never written up in the job description. For example, they may be the first person on the scene for a tragic event, or they might have to provide pastoral care for the families of those who experience chronic stress or trauma. Because of these painful circumstances, the research team also wants to understand how these individuals give themselves space to breathe and to engage in self-care, and how they model to their church that it’s not only acceptable but healthy to do that.

In addition to researchers and teachers, Christin and each of her fellow co-directors are practicing clinicians as well. “We bring a different perspective to our research because we’re actually in the room with clients, either doing psychological testing or therapy throughout the week,” Christin says. As practitioners, the development of these “good ideas” isn’t for the sole purpose of publication and tenure, but more so for their real-life implications for those on the ground—those who Christin says “will never read our articles and don’t know the difference between a doctor and a clinician with a master’s degree, and don’t care,” but who instead want to know, “what does this diagnosis mean for me, really?” Much of this work has to do with embodiment—sitting in the room with someone and submerging herself into the messiness of things.

When Christin speaks about the MultiPJC, it becomes evident that this commitment to acknowledging and sitting in the pain even bleeds over into the lab’s weekly meetings. “A quarter of our lab is Asian American,” she explains, “and as Asian American hate has increased, sometimes we say, ‘we had a plan for lab today and we’re going to completely cancel it.’ In these moments it’s more important to us to create space for the grief, anger, confusion, and exhaustion that often marks these experiences. We want to listen as our research community voices concerns for our own safety and the safety of our loved ones. We want to be able to practice the values that we say we hold as researchers, and sometimes that requires pivoting.”

Those aforementioned values are spelled out in the lab’s very name: multiculturalism, peace, justice, and collaboration. “For multiculturalism, our desire really is to draw on the values and the strengths of various cultural groups,” she says, before providing a practical example of what that looks like beyond representation in membership.

For a project John McConnell and one of his doctoral students are currently working on in Hawaii, they developed a fastidious timeline for traveling to the island, collecting data, and heading home with their findings. When explaining this plan to the elders of the community, however, they were met with pushback. “That’s not how we engage and tell our stories,” they said. “It’s going to be a much longer journey than that.” So the process went from being a couple of months to several years, and has involved multiple trips to the area in addition to a full tour of the community’s holy lands. It’s a perfect example of how the MultiPJC infuses multiculturalism into all aspects of its work, even in terms of how research ought to be collected.

The MultiPJC’s unconventional and radical approach to research is groundbreaking, to say the least, and Christin hopes it can serve as an example to similar institutions, such as Fuller. But she also believes her alma mater is ahead of the curve. “I have rarely seen a school that is seeking to not just say these things but practice them in real life,” she says, “and being able to watch Fuller trailblaze having conversations about intersectionality is one of my greatest joys.”

After living life her way for 40 years, Ines Franklin found Christ—and a calling that had been there all along