When I was 13 years old, my buddy and I rode a go-cart we’d made down a steep hill in San Francisco, determined to make it to the bottom. Well, that didn’t work out for me. When we hit a bump, I flew off that go-cart at top speed and did a face-plant in the road—severely breaking my two front teeth into jagged stubs and scraping up my face something awful. I ran home, looked in the bathroom mirror, and let out a bloodcurdling scream. When my mom rushed in I told her, “I’m not crying because I’m hurt, I’m crying because of the way I look!”

More than 40 years later, as a new therapist, I brought this experience to mind while taking a training class in EMDR—Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing—a type of therapy that can work well for those who have experienced trauma, especially single-incident trauma like mine. EMDR uses a form of rapid eye movement, like what happens when we sleep, perhaps to connect the left and right brain in a way that makes what has been implicit more explicit, helping a person better understand their trauma and move beyond it.

Here’s how it works: The client brings their traumatic memory to mind and holds it—noticing the physical and emotional feelings that memory brings, too—as the therapist moves two fingers, or a light, from side to side and has the client follow that back-and-forth movement with their eyes. Or they might use alternating taps or tones. As they’re doing this, the client will talk about what’s coming to mind for them, and it’s amazing what can emerge because of the left brain to right brain processing that’s going on. Often feelings and perceptions that have been packed away for years come to the surface, and the client is able to see their trauma in a clearer, healthier way that leads to a rewriting of their story.

That’s sure what happened to me in that EMDR training class. As I held that go-cart memory in my mind and followed the other person’s fingers back and forth, it was as if a puzzle piece suddenly fell right into my life story. I realized that when I looked in that bathroom mirror as a 13-year-old I told myself, “I am flawed”—and then spent the next few decades pushing against that flawedness by being a perfectionist, by not allowing myself to enjoy a good moment without wondering if I could do it again. It’s physical for me: an actual knot in my stomach that keeps coming back. When that piece fit in I began to weep, because now I fully saw the core of the meaning I’d made in that traumatic moment.

Seeing myself as flawed can still be a part of my story, as it is for so many of the couples and individuals I now see as a therapist. I’ve worked on rewriting that story for myself—through contemplative and experiential practices, imagery, and breath/body work—so that when my gut tells me, “You’re flawed; you don’t know what you’re doing!” I can take a deep breath and remember that I am participating in the significant work of God. This is the journey I lead my clients through as well: helping them rewrite their stories.

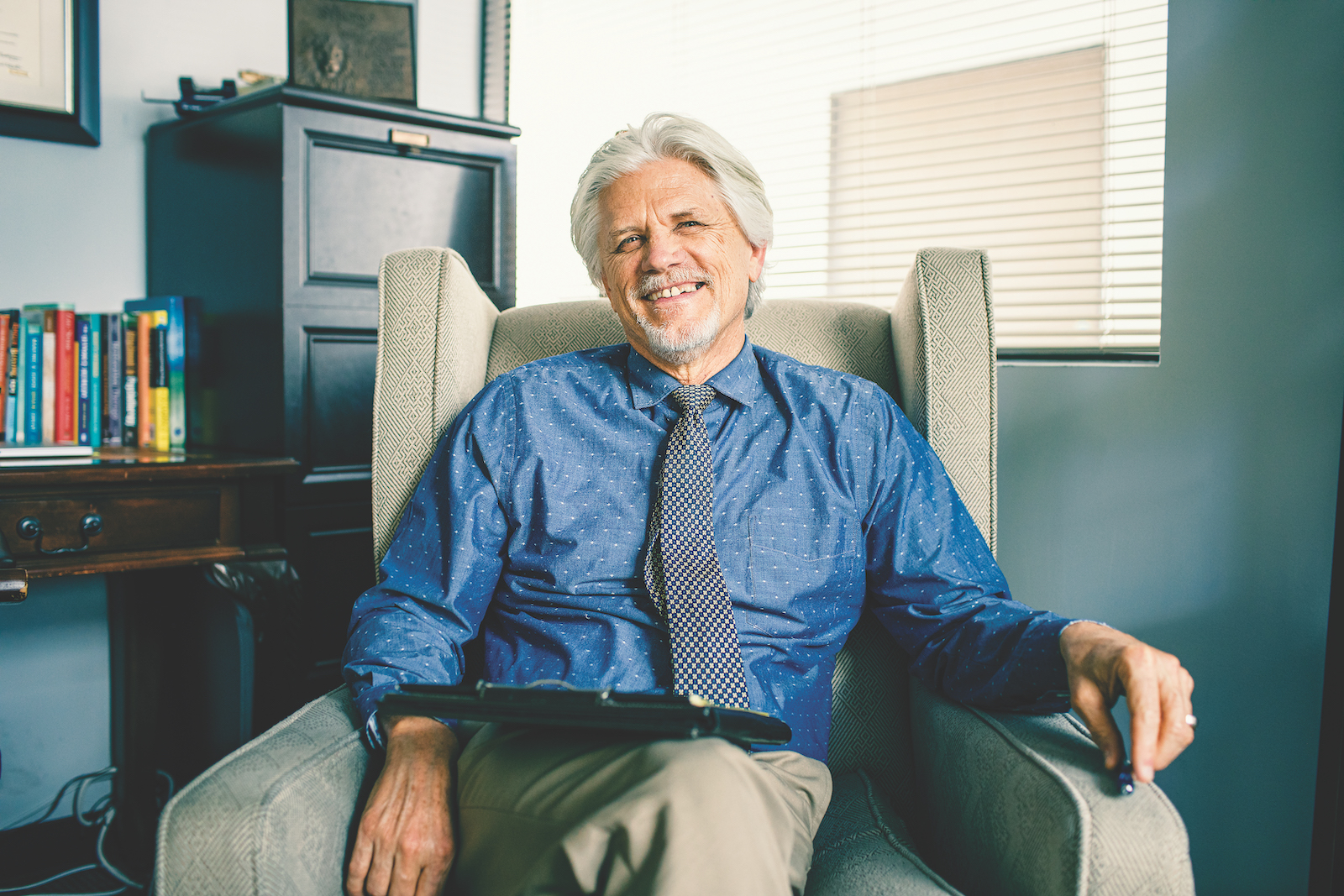

Being a therapist, for me, came later in life. For more than 30 years I was a worship pastor in Texas, where I lived with my family. Once our kids were out of the nest, though, my wife and I had one of those “I don’t know if I want to be with you anymore” experiences—which now, as a therapist, I’ve found are all too common at that stage of life. We had to roll up our sleeves and do some really deep work, but we got through it. And as part of our story-rewriting process, we bought a wedding planning business in Maui, Hawaii!

In Maui I also took on an executive pastor job, found myself doing a lot of pastoral counseling, and discovered over the years that I loved it. My daughter and son-in-law convinced me to apply to Fuller’s MS in Marriage and Family Therapy program, but I put things on hold when our church needed me to serve as interim lead pastor for a while. Then, when the new pastor came and spoke about psychology being ineffective because it looks to the past, I realized this would no longer be a place where I could thrive.

Around that same time, my wife and I had lunch with a couple, and I told them all about my passion for counseling and wanting to grow in my studies. Later that day they called me and said, “We’ve been thinking about what you told us, and we want to cover your expenses to go to Fuller.” They’d had their own positive counseling experience and really valued what I wanted to do. I was stunned by their generosity—that was a $75,000 lunch!

But when we moved to Fuller, within moments my gut started churning. Here I was in my mid-50s, in a place where many of the professors were younger than me and the students half my age. I loved learning and did well academically, but couldn’t shake the sense that I was way past my time. There was that internal voice again: “You are flawed!” Certain people at Fuller were grounding to me, though. Kenichi Yoshida, the director of academic affairs in the Department of Marriage of Family, in particular was so helpful and gracious. We’d meet for lunch each quarter or so and just talk about life, and he’d help me process the struggles I was working through.

Yet I still often felt that my timing was off as an older Fuller student. When I graduated in 2012, I was privileged to give one of the speeches at Commencement. I felt really good about my speech—I even got a hug from Dr. Mouw! But as soon as I left that auditorium I pulled off my cap and gown, even before I went out to see my family. Instead of being able to celebrate being a graduate, a part of me didn’t want to identify as one because that shaming voice told me I was out of season. Now I wish I’d left my cap and gown on a little longer!

Many years later, though, I’m in a good place. I’ve been a therapist at La Vie Counseling Center in Pasadena for several years and love it. Working through my own feelings of being flawed helps me better understand what many of my clients are experiencing. I do a lot of work with couples, and this is my motto: How we love is what brings us together, but it’s how we repair that keeps us together. It’s something my wife and I discovered. Over time, many couples move from positive expectations about their relationship to negative expectations—from “we think so much alike” to focusing on the differences. This can shift even further, from negative expectations to negative characterizations: you’re selfish, you’re an inconsiderate person. That’s harder work to get past, and unfortunately some couples come to therapy too late. Probably three-quarters of the couples I see are able to work through a repairing process, and it’s so rewarding to see them experience the results of our work together.

When a client has experienced a traumatic event, EMDR often helps them as it did me. One of my clients was in a severe car accident caused by a drunk driver. As he was lying on the ground, injured, he saw the drunk driver walking around as if nothing had gone on. Over time this client developed a paranoia: he’d hold a gun behind his back whenever he answered his door, because he felt he couldn’t trust that people would do what they should do. This became the implicit meaning of that accident for him. Through EMDR, we were able to bring that meaning to a more explicit awareness for him, and it caused a shifting in his psychological and physiological reactions so that he could begin to move beyond his trauma.

What we all need in our human experience is someone else’s presence affirming us, a sense of being believed in. To me that’s what the integration of psychology and theology is all about. I worked with one client who was going through a deconstruction and reconstruction of his evangelical faith. As he moved through that, he reached out to someone who was an influential part of his past and got a very judgmental response. He read it to me—it was a very harsh letter—yet my client didn’t show a bit of emotion as he read it. With permission, I reached over and held his hands, looked into his eyes and said, “Here’s what I would write to you instead.” As I spoke words of affirmation instead of criticism, we both began to cry. Because someone looked at him eye to eye and said, you’re not alone, I’m here with you, it regenerated a feeling for him. We were then able to process this because instead of feeling judged for what he was trying to authentically discover, he felt safe.

These are the experiences that keep me going. They chase away that internal voice telling me I’m flawed and remind me instead that I’m part of the significant work of God. Whether it’s using EMDR or another form of therapy, I love being able to journey with people through their experiences, often painful ones, and see them begin on their own to rewrite the meanings they thought were indelible. I can’t help anybody forget that something difficult happened; we can’t rewrite their history. But over time we might find a different meaning for their story. We journey together from being flawed to being human, and that inspires me.