It is our contention that we see a movie best when we look not only at its aesthetic and cultural achievements, but at its spiritual or theological import as well. This is the guiding conviction of our work. We believe that one might meet God at the movies, that the silver screen can be an intermediary for interacting with God.

This can happen without our being prepared for it. God sometimes takes over our experience of the world and blasts us with God’s presence. We have catalogued hundreds of stories of God doing exactly this at the movies. This can also happen because we come primed to hear from God at the movies, when we position ourselves to encounter a revelation like that experienced by mountaineers and musicians. Part of that encounter is rooted in our willingness to meet God in this way.

Part of it is in the filmmakers’ intent. Sometimes filmmakers themselves approach their work with a similar hope of encountering God in their movie-making. As Martin Scorsese said recently, “If you work [as if filmmaking is a spiritual practice] and you have got a gift, then your work is like a prayer. When you go to work, it’s praying.” When filmmakers seek truth in their work and endeavor to represent the truth they know genuinely, it is all the more likely that we might encounter God’s truth in their films.

Below, in chronological order, are the twenty films from the past decade that our community feels best represent this peculiar intermingling of audience posture and filmmaker intent. We made this list by choosing from among two hundred films, twenty from each year, that we previously chose at the best of their respective years. Each of us chose twenty films, and then we tallied the results. The twenty films with the most “votes” made this list. We chose not to present our list in ranked order, though if you are curious, The Tree of Life received the most votes from our group, as you might have predicted.

Many have made “best of the decade” lists recently. There is some overlap between our lists and theirs, as there should be, since we are all of us devoted to seeking truth, goodness, and beauty in this art form that we love. But there are a few anomalies on our list as well, as there should be, since what we reckon as true, good, and beautiful is shaped by our faith in Christ explicitly.

We hope that this list of films will make you grateful for all the good we have seen at the movies this past decade. We hope it will make you hopeful for the good we are likely to see in the decade to come. As Jesus said, “Keep watch! Because you do not know when the owner of the house will come back—whether in the evening, or at midnight, or when the rooster crows, or at dawn,” or when you are at the movies! as we, at Reel Spirituality, might dare to add.

—Elijah Davidson, Co Director and Managing Editor, Reel Spirituality

The following members of our community participated in creating this list: Samuel Anderson, Matt Aughtry, Catherine Barsotti, Kutter Callaway, Bob Davidson, Elijah Davidson, Craig Detweiler, Lauralee Farrer, Asher Gelzer-Govatos, Richard Goodwin, Roslyn Hernandez, Gary Ingle, Robert Johnston, Andrew C. Neel, Kevin Nye, Ruth Schmidt, Andy Singleterry, Avril Speaks, Colin Stacy, Jonathan Stoner, Eugene Suen, Kent Webber, Justin Wells, and Ralph Winter.

There are films that each of us would have wanted to see on this list that did not make the final cut. We offer these honorable mentions: 12 Years A Slave, A Hidden Life, A Separation, The Act of Killing, Beasts of the Southern Wild, Birdman, Black Swan, Ex Machina, The Farewell, Fruitvale Station, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Gravity, Holy Motors, Ida, Inside Out, The Irishman, La La Land, Logan, Mad Max: Fury Road, Minding the Gap, Phantom Thread, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Under the Skin, and The Wolf of Wall Street.

Of Gods and Men

One of the finest religious films, and one of the best Catholic films, in years. The film won the Ecumenical Prize at Cannes 2010. It also won the Grand Prix du Jury from the festival itself.

The subject is the Trappist community of Mt Atlas, Algeria, in the 1990s. Living their monastic life amongst the local people and ministering to them, especially with medical services, they were viewed more and more with suspicion in the country – especially because they were French expatriates – by government troops who were becoming more active against the increasing terrorist attacks, and by the terrorists themselves. Seven of the monks were killed in the latter part of May 1996.

While the film expertly builds up the background of post-colonial Algeria, corrupt government, and extreme Islamists imposing something like Taliban terror in the towns and villages… the centre of the film is the life of the monks and their preparation for death.

For an audience wanting to know and understand something deeper about Christian spirituality, something deeper underlying, despite the sins and failures of the church and of church people and the consequent anger at abuse and scandals, these scenes offer a great deal to ponder.

+ Read more about Of Gods and Men in this article from Rev. Peter Malone

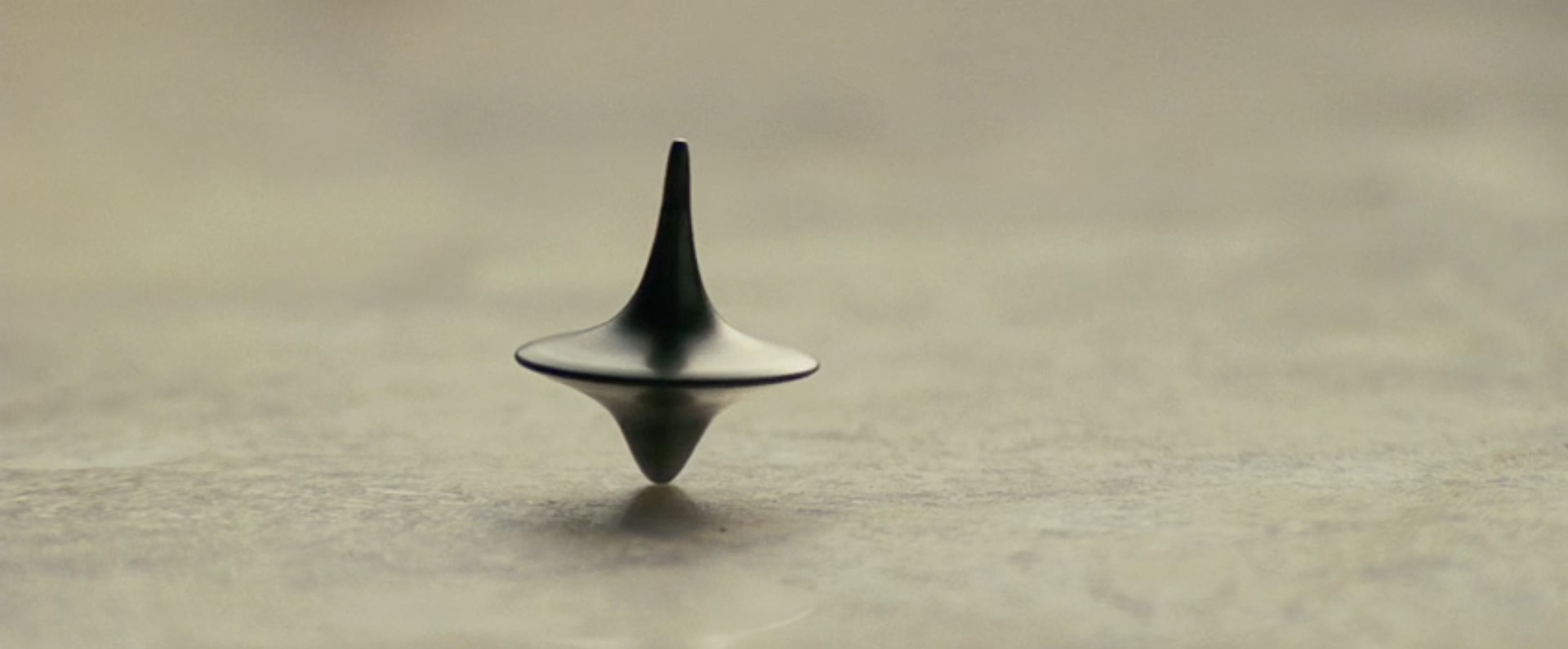

Inception

Christopher Nolan has crafted a story of unbelievable detail and complexity. Inception’s world obeys very particular rules. It must for the story to hold together, but the story is such that it could oh so easily have slipped out of Nolan’s hands, fallen to the earth, and crashed into a million confusing pieces. He somehow maintains the narrative, though it is a breathless endeavor. The story concerns (and questions) multiple realities, and yet somehow it is accessible and understandable. Like a delicate chandelier, Inception is magnificent.

Christopher Nolan is one of a few filmmakers who represent the postmodern inclination in current, mainstream cinema. Nolan’s postmodern leanings fall into the realm of epistemology, or how we know what we know. He often accomplishes this through the manipulation of time. Memento tells its story backwards, Insomnia occurs in a place where the sun never sets and it therefore without time, The Prestige happens all out of order, and Inception, well, if you’ve seen it, you know.

Postmodern thought is defined by its questioning of what we profess to know. It is for this reason, I think, that so many in the evangelical world are threatened by post-modern thinking. After all, the evangelical flavor of Christianity is characterized by a profession of what we believe to be true. Postmodernism questions whether or not we can truly know anything to be absolutely true. Postmodernism doesn’t question the existence of absolute truth; it questions whether we are capable of grasping that absolute truth.

Nolan has wrestled with this question again and again. It is not outside the scope (or responsibility) of Christianity to deal with these same questions. Yes, we are beholden to the Ultimate Absolute Truth, but we would do well to be a bit more humble in our affirmations of what we know about God and how we know God. If the popularity of certain movies is any indication of the thoughts and inclinations of our society at large, this conversation about how we know what we know is one we’ll be having more and more in the coming years.

+ Read more about Inception in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

The Tree of Life

The movie opens with a quotation from Job 38: 4, 7: “Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundations? [… while] the morning stars sang together and all the angels shouted for joy?” Here, in the Book of Job, Malick found an archetypal pattern around which to build his story; here would be the trajectory of Jack O’Brian’s life story. Now a successful, middle-aged architect working in a sleek, urban skyscraper and living in a beautiful tree-lined suburb, Jack (Sean Penn) is unable to come to terms with the tragic death of his younger brother at nineteen. It is his struggle which gives shape and “thickness” to the film. In particular, it is his perception of his parents’ agony that colors all else, even Jack’s present existence.

Some who have seen the movie criticize it for not having a typical narrative arch. But Malick’s interest is elsewhere. He is not trying to tell a story. As with Job, he is trying to understand the sometimes senselessness of life. The “slaughter of an innocent” has threatened to destroy a family. It has even put the universe’s meaning in doubt. “Where were you God?” “Did you know?” “I believed in you?” “I want to see what you see?” “What was it that you were showing me?” The Tree of Life becomes an extended meditation on loss. And like Job, it ends with a hard won, but real, epiphany of the God who holds it all in his hands. Grief transmutes into surrender, and nature into grace. Many will leave the theater in awe at experiencing divine mystery.

+ Read more about The Tree of Life in Rob Johnston’s article about the film

Malick juxtaposes the way of grace and the way of nature. He references the Apostle Paul’s meditation of love. Grace doesn’t try to please itself; it accepts insults and injuries. The screenplay suggests Nature lords power over us, finding reasons to be hungry rather than satisfied. What is our calling? To be true to God, whatever comes our way.

While such lofty ambitions could come across as stifling, Tree of Life brims with vitality. It puts such ultimate choices inside a young boy’s mind. Hunter McCracken makes a remarkable debut as “Young Jack.” Brad Pitt is equally engaging, combining the soul of a church organist with the frustrations of a failed inventor. He teaches his sons how to box because life is going to throw plenty of punches their way. Jessica Chastain is cast as mother earth, utterly unflappable and almost silent amidst the trials of her household. Is the family too iconic? Are the roles of Mother and Father and Son elevated into type? Surely that is Malick’s point—the entire human drama and even the cosmos itself is contained in one Texas family. As 2001: A Space Odyssey compressed the history of human progress from one weapon (a bone) to another (a spaceship), so Tree of Life leaps from the Creation to a womb. Deal with it, people. Rediscover the wonder of the nuclear family, from the Fall in the garden, to the tragic reality of brother versus brother.

+ Read more about The Tree of Life in Craig Detweiler’s article on the film

The Master

A film called The Master, about one man’s powerful hold over another, thus becomes an exploration of two weak men, one of whom is exploiting people’s past for money, while the other is suffering PTSD and groping around for relief from his past, unable to find it in his excesses. The power comes from the dialectic when these two weak forces meet: for Freddie’s natural urge is to throw himself entirely into the method and excessive loyal obedience to Dodd.

And this is the major point of interest for me, because the film brilliantly examines what can happen when you believe something too much. If you stick with the belief, either it destroys you (which the method very nearly does to Freddie) or you destroy it. Freddie very nearly does destroy ‘the method’ with his violent outbursts, but the key scene here comes towards the end, when, out in the desert, Dodd tells Freddie to jump on a motorbike, pick a point in the distance, ride as fast as he can, and just go for it.

And Freddie does. He obeys precisely. But the effect that this total obedience to the method produces is his exit from the method: he keeps on riding, riding, riding, leaving Dodd far behind, never to return. Excessive belief nearly killed him, yet by following it through to its farthest conclusions, it ended up saving him, by destroying itself within him.

+ Read more about The Master in Kester Brewin’s article on the film

The Master is a frank look at “the least of these,” and is actually a portrait of ministry in action, even if the minister in this case is selling nonsense in the end. We’ve been taught for years that iron sharpens iron. In The Master, we see the scabbards clashing but little sharpening being done. Freddie Quell is in the same group of poor, miscreant losers that Christ first called when He started his church. If we passed such as them in the street today we would hardly take notice. They seem to be lost causes, past hope, and past help. As we are fond of saying in the faith, though, upon their worn faces are the lines of Jesus.

The Master reminds us that the walk of faith is a long-distance haul, fraught with reverse movement and continuous letdowns. Whoever said that Christianity is a long obedience in the same direction had it right. Change is hard, and when a person is comfortable in his patterns and addictions, change can be nearly impossible. Yet, our ministry with people and to people is the same. We walk together, in continuous search for our true selves. The Master illustrates how messy this process can be for all parties involved.

+ Read more about The Master in Kevin Marks’ article on the film

Her

Theodore’s relationship with Samantha is very much like Adam’s relationship with God prior to Eve’s creation. God and Adam were together in the Garden, but it wasn’t enough. God wasn’t present physically, and so Adam was alone. God recognized that this wasn’t good, so God made Eve, a physical being to be with Adam. As Samantha’s intelligence and existence expands beyond Theodore’s, Theodore’s loneliness, which had been tempered by Samantha, reignites with a fury. Both of them need the kind of presence they can only get with others like them. It’s not good for Theodore to be alone.

Fast-forwarding through human history a few thousand years, we see Christ, God incarnate, come to be with humanity. There are lots of reasons for the Incarnation, but I suspect one of them was that God wanted to be with the ones God loves. Eventually, Christ is resurrected into a new state of being. He ascends, and he promises that he will return to take us with him into that new state of existence. In the mean time, Christ exhorts us to be with one another, to love each other in the fullness of our physical humanness.

So, my relationship with Christ right now, often looks like Theodore’s relationship with Samantha. We speak via prayer as Theodore and Samantha speak via phone. It’s a healthy relationship, live-changing, actually, but Christ outreaches me, and I need my next door neighbor.

+ Read more about Her in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

Short Term 12

Short Term 12 is a simple and yet beautiful movie. It is its simplicity that makes it so powerful. As we journey with Grace, we viscerally experience her struggle to process her buried past as it rapidly resurrects. Short Term 12 doesn’t over dramatize or too quickly resolve its characters’ struggles. The movie allows us to sit with Grace in the messiness of it all. Cretton neither glorifies the messiness nor minimizes it, rather he invites us to be there as an unseen friend who is offered the privilege of journeying with Grace.

She is offered choices. Each hurdle or challenge is a chance to engage with a fear birthed in her past and to move with boldness into a different way of being. Grace is given the chance to transform the coping patterns that are no longer working for her into a new life. Isn’t this what we as humans are each offered? The chance, to shed our protective walls when we get to a place where we no longer need that protection?

+ Read more about Short Term 12 in Jessi Knipple’s original review of the film

In his opus on the necessity of a transcendent reality as the basis for all true art, Real Presences, George Steiner contends eloquently that it is because humans live in this liminal state that humans make art and need to make art.

After briefly discussing how much the Christian church likes to focus on Good Friday and Easter Sunday, Steiner writes, “But ours is the long day’s journey of the Saturday. Between suffering, aloneness, unutterable waste on the one hand and the dream of liberation, of rebirth on the other. In the face of the torture of a child, of the death of love which is Friday, even the greatest art and poetry are almost helpless. In the Utopia of the Sunday, the aesthetic will, presumably, no longer have logic or necessity.”

The “suffering, aloneness, unutterable waste”–these are the places where Destin Daniel Cretton’s stories begin. Children are being tortured. Loves have died. Grace cannot express herself to her boyfriend or connect genuinely with others. “The greatest art and poetry are almost helpless.”

But the stories never quite reach “liberation” or “rebirth” either. As the stories close, we are still far from Utopia. Cretton’s stories point to that place, but his characters are not there yet. If they were, perhaps as Steiner argues, “the aesthetic [would], presumably, no longer have logic or necessity.” And surely the aesthetic is necessary. Otherwise, why make a film?

+ Read more about Short Term 12 in Elijah Davidson’s article on the films of Destin Daniel Cretton

Calvary

There is still more to love about this film—its “High Noon” structure and “Searchers” cinematography, it’s Hitchcockian tone, the way it swings between classic, Capra-esque sentimentality and black, Coen-esque comedy. Brendan Gleeson, as I said before, is unbelievably good as Father James, but Kellly Reilly’s “Fiona” is also integral to the film, and Reilly’s performance grants the character a depth of sadness and love that really sells the film’s ending. Finally, Calvary includes a few of the most harrowing and heartbreaking scenes you are likely to see in a film this year. Watch especially for the scenes Gleeson shares with his real-life son, Domhnall Gleeson, with Marie-Josée Croze, and with little Anabel Sweeney.

I cannot imagine I will see a film this year that I will recommend more highly than Calvary. I particularly believe that every pastor and pastor-in-training should see it. Not since Of Gods and Men have I seen a film that takes as seriously the role of a minister, the Church, and practical spirituality in society, and I’ve never seen a film treat those things as favorably while being as entertaining and cinematically astute.

+ Read more about Calvary in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

I may have never seen clerical life portrayed in cinema with such a sense of realistic nuance as that found in the writer-director John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary, for my money the film of the year, in which Brendan Gleeson’s Father James stands rock steady and open – he’s enormous and strong, microscopically interested and tender, a believer and a doubter, a Santa Claus with a salty mouth, as if Mt Rushmore had a sense of humor or the Grand Canyon could weep. Father James knows from the first minute of the story that he’s being threatened with murder – a symbolic act being planned by a victim (not yet, I think, a survivor) of monstrous injustice who believes that killing a decent priest would be noticed more than killing a bad one. It’s a mythic hook, and not just biblical myth, for Calvary is redolent with the history of cinematic portrayals of lonely men framed against a chorus of disapproval – High Noon comes to mind, with one good person trying to keep it together amidst the projections of multitudes.

A priest friend told me once that he seeks to cope with the temptations of ego by recognizing the distinction between vocation and persona – presiding at a celebrity wedding should be no more important than doing it for the blokes down the street; it’s easier to stay emotionally healthy and avoid the traps of selfish ambition when he sees himself as working with the grain of vocation. Father James, in Calvary, seeks to serve, but he’s not innocent nor illusioned. He’s the kind of priest that the Jesus of The Last Temptation of Christ would affirm. Just ask yourself how can I be of service, and try to do your best in that moment, and you’ll be ok. Even if they kill you. Emotionally healthy service is like radio waves in a perfect acoustic chamber – it bounces back on the one serving, like a smile from the face of God.

+ Read more about Calvary in Gareth Higgins’ article on the film

Boyhood

Mason’s story is presented as a amalgam of all of the in-between, ordinary moments of life. These moments include Mason riding his bike with his friends, asking his dad if elves and magic are real, going camping with his dad while talking about nothing and everything, receiving a gun, a Bible, and a blue suit for his fifteenth birthday (the film does take place in Texas after all), sitting in on his mom’s college class, and aimlessly wandering around town at an overnight college visit with his girlfriend. These moments are what make up the heart of the film.

The meaning in these ordinary moments is usually not fully grasped by Mason (or the audience) while he is experiencing them. For instance, early in the film Mason helps his mom move out of their house by painting over all of the pencil markings on the door frame that show his height throughout the years. This moment carries greater weight when contrasted with a moment later in the film as Mason is ready to move out and head off to college. Even though he has become very passionate about the art of photography, he wants to leave behind the frame with the first picture that he had ever taken. In both scenes, these reminders of important moments in Mason’s life are cast aside in favor of moving forward with the rest of life.

Important moments like these can certainly affect the trajectories of our lives, but Boyhood reminds us that life is primarily made up of ordinary moments. The monumental moments in our lives are not necessarily the most obviously important ones. The best times in life are the everyday, mundane moments of our existence in which we can simply enjoy being alive for the sake of life itself. Rejoicing in the everyday moments is what life is all about.

+ Read more about Boyhood in Gary Ingle’s original review of the film

Often, we look for meaning in the words the characters speak, but most often, real meaning is found in their actions and in the way the filmmaker tells her or his story.

As you watch Boyhood try to figure out what it means that this film was shot little by little over the course of many years. What do the way Boyhood was made and the kinds of things the filmmakers choose to focus on communicate to you? How does the way Boyhood views life encourage you to view your own life? The more I’ve thought about it, the more I like what it encourages in me. I think you will feel the same yourself.

+ Read more about Boyhood in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

Silence

On January 6, 2017, we had the privilege of screening Silence for a packed-house of Fuller community members in Pasadena. After the film, we were honored to be joined by legendary filmmaker Martin Scorsese for a conversation about his challenging, masterful film. Watch this film of the conversation and Scorsese’s subsequent visit to Fuller’s campus.

+ Watch our conversation with Martin Scorsese about Silence

Silence is in awe of the martyrs’ faithfulness to Christ in this, the most dire of circumstances. Scorsese even dedicates the film to those Christians and their pastors. Rodrigues’ faith is differently shaded, a contested faith seeking steady footing in a world of cultural complications and theological contradictions. Silence longs for Rodrigues’ conflicted faith to find a place among the pure faith of the martyrs. It insists upon it, almost desperately.

Reflecting on the film a few days after seeing it, I find myself praying that God’s mercy is wide enough to include both uncritical and critical confessors. I know “there’s a wideness in God’s mercy I cannot find in my own,” and all of our theological pondering and posturing does nothing to expand or contract God’s love, a love that radiates upon history of its own accord, seeping into even the most remote and “unreachable” corners of Creation and of the human heart, a love that “will not let me go,” even when I let go of it.

Rodrigues is a fictional character, but he’s based on a real man, Guiseppe Chiara, and I hope he found peace. I hope the real Christians that sheltered men like him found peace. I hope their persecutors did too. I hope Endo found peace. I hope Scorsese finds peace. I hope I find peace. I hope we all find peace. We cry out for God to reassure us, to quiet our doubts. Perhaps God’s answer is God’s silence, a presence that says stronger than any speech, “I’m here. I’ve always been here. I’ll always be here. Rest your head upon my bosom. Be at peace.”

+ Read more about Silence in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

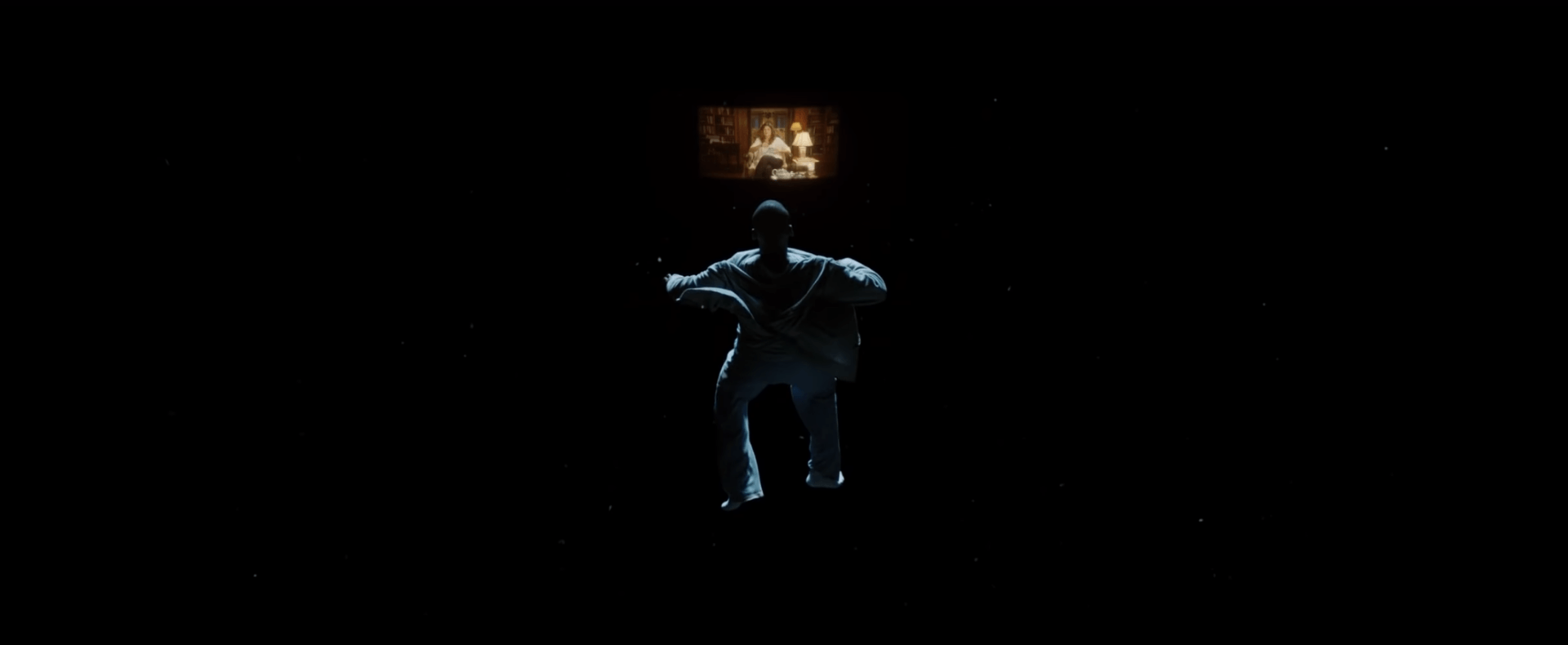

Moonlight

As Ang Lee did in Brokeback Mountain, Barry Jenkins introduces a gay character into an aggressively masculine environment to highlight the destructive nature of hyper-masculinity and to lament the lack of a more gentle and loving form of masculinity in that culture. For any society to function properly, it must integrate its masculine and feminine aspects in healthy ways. Even Chiron swings to one extreme in the final third of this film, and the movie laments this. Moonlight’s use of music is one of its particularly cinematic aspects. Notice how Chiron’s life is scored when he’s being true to himself compared to how it is scored when he isn’t. Regardless of how self-assured he appears scene-to-scene, his true self is echoed in how the movie sounds.

Now “blue.” Moonlight is a steadfastly melancholy film. There is a persistent sadness to Chiron’s life, first because he is picked on by other boys and does not have a father to protect him; then because his mother descends deeper into her drug addiction, rendering him homeless, a circumstance that mirrors his inability to find a place where his burgeoning sexuality fits within his culture; and then finally because he has grown into a deeply repressed man, successful in appearance but failing miserably at being true to himself. Melancholy is “sweet sadness,” and Chiron’s sweet moments are blue as well, near the endless azure sea or awash in the breeze coming off of it where he is held lovingly by other men.

+ Read more about Moonlight in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

Moonlight is an artfully told story that both critiques and subverts Hollywood’s racially stereotyped portrayals of African-Americans in low income communities. Where we expect to find violence and apathy in Juan’s character we find gentle resolve and fatherly concern. Instead of providing us with a colorless and banal cinematic exploration into sexual identity, Moonlight offers a refreshingly dynamic and deeply contextual story on what it means to be black and gay. Its authenticity refuses to offer oversimplifications, yet its dynamism leaves filmgoers with hope. You can either perceive Chiron’s journey as a fraught attempt to assert his gay identity in his community, or you can accept it as an assertion that his attempt to decide who he wants to be on his own is not enough for him to establish his self.

Coming from a relationally dependent or, better, an interdependent model of anthropology, Miroslav Volf answers that genuine self-discovery is a repeated and contextual act of embrace between the self and the other. We need an open, loving community that is willing to embrace the “other” and we also need to have a willingness to be open to that community in order to understand ourselves and find fulfilling relationships. Without community, we will neither find affirmation for who we already believe ourselves to be nor discover who we can be; also, without embracing the other(s) in our life, we will never come to relationally understand the other, which usually engenders fear or hate of the other.

+ Read more about Moonlight in Christopher Lopez’s original review of the film

Arrival

Arrival is about language and translation. Amy Adams’ character Louise is brought in not because she is the foremost scholar in language, but because she has a particular view of studying language. She believes that language is the foundation of any society, in both a creating and limiting capacity. A society’s language shapes their identity and culture in an unmistakable way. When the US military considers another translator, she tells them to ask him the Sanskrit word for “war.” When they return, she confirms to them that the Sanskrit word for “war” literally means “the desire for more cows.” Louise is chosen for the mission because of her nuanced understanding of how language shapes us, not just how we shape language.

As the various countries deal in their own way with translating the aliens’ language and communicating with them, they start to arrive at different conclusions. We learn that some cultures do not have different words for “weapon” and “tool,” which becomes a stumbling block when trying to discern the motives of the visitors. The point here is endlessly fascinating: how does language shape and limit our ability to imagine, especially with those who are completely different from us? I thought of the old saying, “The Inuits have 50 words for snow.” How limited is our capacity in English to talk about and think about snow, versus the Inuit language, which allows for nuanced, detailed conversations about it? How much is their relationship to their physical world different from ours? The movie suggests that different languages, and by extension cultures, create realities that limit possible outcomes.

+ Read more about Arrival in Kevin Nye’s original review of the film

First Reformed

Upon the release of First Reformed, we were honored to host writer/director Paul Schrader for two days of film screenings and conversations about his film and about his theory of spirituality in film, what he terms the “transcendental style.”

+ Watch our many conversations with Paul Schrader about First Reformed

Lady Bird

Very early in the film – indeed, it’s one of the first lines – ‘Lady Bird’ and her mother are listening to the end of Grapes of Wrath on an audiobook on their way home from a tour of colleges the girl might attend in California. They are driving through California’s central valley, the location the events at the end of that book largely take place. Reflecting on the book, ‘Lady Bird’ says, “I wish I could live through something.” Given it’s 2002 when the story begins, ‘Lady Bird’ will likely finish college in 2008, laden with thousands and thousands of dollars in student loan debt, right as the Great Recession descends on the country. Oh, you’re going to ‘live through something,” girl. Yes, you are.

This kind of knowing retrospect washes over all of Lady Bird. It’s this sense that makes it feel like an apology. “I didn’t know how good I had it. I didn’t appreciate it appropriately at the time.” Most of the film focuses squarely on ‘Lady Bird’ life, but there are key moments that deviate from her lived experience. Mostly these focus on her mother (Laurie Metcalf giving a prickly, heart-breaking performance). ‘Lady Bird’ the character thinks the worst of her mother. Lady Bird the movie thinks the best. The movie’s perspective wins out.

+ Read more about Lady Bird in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

Get Out

Get Out will endure not simply as a technically proficient or classic film, but will forever be embedded in the cultural psyche of this tumultuous time. Get Out reflects not only our deepest fears and darkest sins, but its success might just represent out willingness to confront them and the hope that it doesn’t have to always be this way. From a bird’s eye view, Get Out may be among the year’s many great films, but in the lived experience of America in 2017, it might be the most defining and significant film of the year.

+ Read more about Get Out in our list of the best film’s of its year

Coco

The level of detail in every aspect of the film is astonishing. The massive amount of research done by Pixar is evident from the holiday aesthetics, to Mexican architecture, to the look of the characters, the history of popular music and other types of Mexican art, to the historical celebrities. Even the protagonist’s pet is incredibly true to the real life inspiration! That list could go on and on, but enough of that.

In Coco, 12 year-old Miguel finds his family’s traditional stance towards music at odds with his dream of being like his idol, the greatest Mexican singer ever, Ernesto de la Cruz. In an attempt to seize his moment to follow his dream, Miguel and his loyal companion, his stray dog, Dante, find themselves going on an adventure into the world of the dead.

In terms of story, Coco does not shy away from an issue that is common in many cultures – single parent families. The particular dynamic of an absent father figure is very important to the story. As a result we are able to see some of the layers and roles of the traditional Mexican family structure. One of my favorite roles explored in Coco is that of the loving, strong, respected, and sometimes domineering matriarchs. In this aspect, Coco admires the resiliency of Mexican women, and celebrates the importance of family.

+ Read more about Coco in Roslyn Hernandez’s original review of the film

Dunkirk

Christopher Nolan seems to be taken with Andrei Tarkovsky’s famous dictum that a film is “a mosaic made of time.” In every film Nolan has made except for his second two Batman films, the reorganization or manipulation of time has been a key component of each film’s narrative. In Nolan’s films, events fold over on top of each other so that the present moment is intensified. The paramount moment in a Nolan film isn’t merely itself, it is every other moment in the narrative as well. Everything that happened before and everything that will ever happen after that most important moment is warped by that instant, so Nolan incorporates narrative devices – anterograde amnesia, perpetual daylight, doubles and illusion, dream logic, black holes – to warp his characters’ experience of and interaction with the world. The formal convention of editing allows him to create these “time stacks” with higher emotional fidelity than any other artistic medium allows, save ritual. (In Christian worship, for example, the Communion ritual is a moment in which the participants are joined metaphysically with all those who have come before and all those who will come after them in time.)

Dunkirk draws everyone together, and beyond the constant threat of German bombs and bullets, the key antagonists in the film are the various character qualities that would keep the players apart, qualities like cowardice, hopelessness, chauvinism, self-regard, and shame. One could wrap all those qualities under a single quality, perhaps – lack of vision. When characters are unable to perceive a reality outside themselves, to imagine a good end to their predicament, they revert to selfish behaviors. They have to see beyond the moment to the ways their actions ripple into the future in order to do what is required in the moment. Nolan’s time-layered narrative carries his characters and us, his audience, into the future, prompting us to reckon with what has come before and reach toward what could be if we have the courage to do what’s needed now. “I am English!” is the first line of the film. It’s a plea, and the film that follows is a similar appeal to save the present from our myopic visions clouded by fear. Dunkirk shows us the best of what “English” has been in the past. May we live up to that example in the future.

+ Read more about Dunkirk in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

Roma

I am aglow. Roma is cinematic spirit-wind sweeping into the locked room of my heart, casting out the late-year malaise, and baptizing my eyes with new sight. If I speak with the tongues of men and angels, it is because I am in love with Roma. If I can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, it’s because Roma first revealed them to me. If I give all I possess to the poor and welcome hardship, it is not to earn anyone’s favor. I am favored already, I know, because I have seen Roma and it has opened my eyes.

+ Read more about Roma in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film

Black Panther

Where Black Panther succeeds most thematically is by not trying to prove that racism exists -that America and countries all over the world have oppressed black people and black communities for millennia. It simply assumes it. The movie engages in a kind of unabashed truth-telling that is less about being prophetic or preachy than it is about being honest. Through Coogler’s deft directing and writing, the story makes a brilliant move to set the film’s primary conflict within Wakanda itself. The film comments on racism, representation, and black power by its mere existence, and refuses to apologize for it. It then uses its world to rehearse the conflict that we face in our own nation right now: hoarding resources, valuing security over hospitality, and building literal and figurative walls to keep others out and ourselves in.

Black Panther is more than a movie. It is more, even, than a cultural moment, but is actually a movement. It’s a shift that may take years to understand and uncover, but its influence is already felt in movie theaters filled with kids from communities brutalized by racist systems, and celebrities pledging millions of dollars to organizations that lift those communities up. As a seeker of God’s justice, I love what this movie has inspired in our culture, and hope it never stops. As a lover of movies, I look forward to the franchise that this movie launched, and the works of countless filmmakers, actors, writers, and other artists that it will inspire.

+ Read more about Black Panther in Kevin Nye’s original review of the film

Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

In a stirring new documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? director Morgan Neville examines what must surely be one of the more impactful, yet curious lives of the 20th century, and in turn, unpacks what it means to be a neighbor in the truest sense.

For several generations of children spanning the 1960’s through the late 90’s, Mister Rogers was a counselor, a confidant, a guide, a friend, a surrogate parent, and ahem, a neighbor. For those of us who grew up with him and his perpetual public television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, our trust and belief in him were absolute, even if the man himself remained lodged firmly in TV/childhood folklore.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? reveals that all our suspicions were true—Fred Rogers could be trusted implicitly, and his onscreen persona and character mirrored that of the actual man. Furthermore, his devotion to children and truth-telling on their behalf qualifies him squarely for some elevated office of cultural saint.

+ Read more about Won’t You Be My Neighbor? in Kevin Marks’ original review of the film

Parasite

With a title like Parasite, one might expect there to be some sort of lurking creature or alien lifeforce, akin to Jessica Hausner’s excellent Little Joe. But Joon Ho abandons the sci-fi genre entirely, anchoring the narrative in down-to-earth circumstances (albeit with signature Joon Ho wackiness and black humor). It’s a tragicomedy, a hilarious horror, and a family drama, all somehow maintaining its integrity. In other words, Joon Ho upends any sense of categorization or what a film is “supposed” to do. It’s absolutely thrilling to watch, mostly due to the suspense and mystery, but also because we can sense that we’re watching something revolutionary unfold before us, that the boundaries and definitions of what cinema can be and do are expanding right before our eyes.

+ Read more about Parasite in Joel Mayward’s original review of the film

Like any great storyteller, Bong knows how to weave particular, nigh-personal details into symbolic, nigh-iconic situations. You connect with enough of what’s going on to keep you curious about what you don’t understand. Great songwriters do this best, like Bob Dylan or Paul Simon. Or, in the movies, Hitchcock. All that to say, a lot of what happens in Parasite is culturally specific, but it is also fun to learn more about another culture. You’ll learn little bits about Korean culture while you watch the film, and then you’ll learn more afterwards when you go online to read the why behind the moments you know matter in Parasite but lack the cultural awareness to fully understand.

All of Bong’s films are about family and class and the hazards of living in a globalized world. Common concerns. They are all funny and heartbreaking and suspenseful too. Parasite includes the funniest scene I’ve seen all year—it involves a text message—the most discomfiting—it involves a coffee table—and the most heartbreaking—it involves stairs. All three of these scenes happen within fifteen minutes of each other, and all three tilt the emotional balance of the movie in unexpected ways. Parasite is a wonder.

+ Read more about Parasite in Elijah Davidson’s original review of the film