When people are sick, they have many questions: Why am I sick? Is God causing my illness or a demon? Did I sin? Do I see a doctor or pray? Illness, especially if severe, threatens our identity and security. How we understand illness affects our physical, psychological, and spiritual health, as well as our response to illness. Misunderstanding can be costly in terms of incorrect treatment (e.g., prayer when a pill is also needed) and/or intensified suffering (e.g., guilt when an illness is caused by natural factors). Yet confusion abounds. People often limit healing to the physical body, and assume a straightforward relationship between sickness and healing. Responses are inconsistent. I have seen patients give up on God and life after being diagnosed with a terminal illness. I have seen people request prayer for healing and, almost shamefully, see a doctor as well. Others seek medical treatment only after prayer has “failed,” or vice versa. One of my patients was suffering from a serious depression treated with medication. She assured me “this is where God wants me to be.” I wondered why she was taking antidepressant medication.

Christians seem to have two types of responses. Some stoically accept that God has some mysterious plan and may boast about their sickness. Others expect, indeed demand, perfect health. They obsess about their bodies, always trying the latest health fad. This can be viewed as idolatry. Many Christians appear to assume a dichotomy between medical treatment and divine healing—it is either one or the other. Some are suspicious of professional health care, and equate science with scientism, the worship of science.

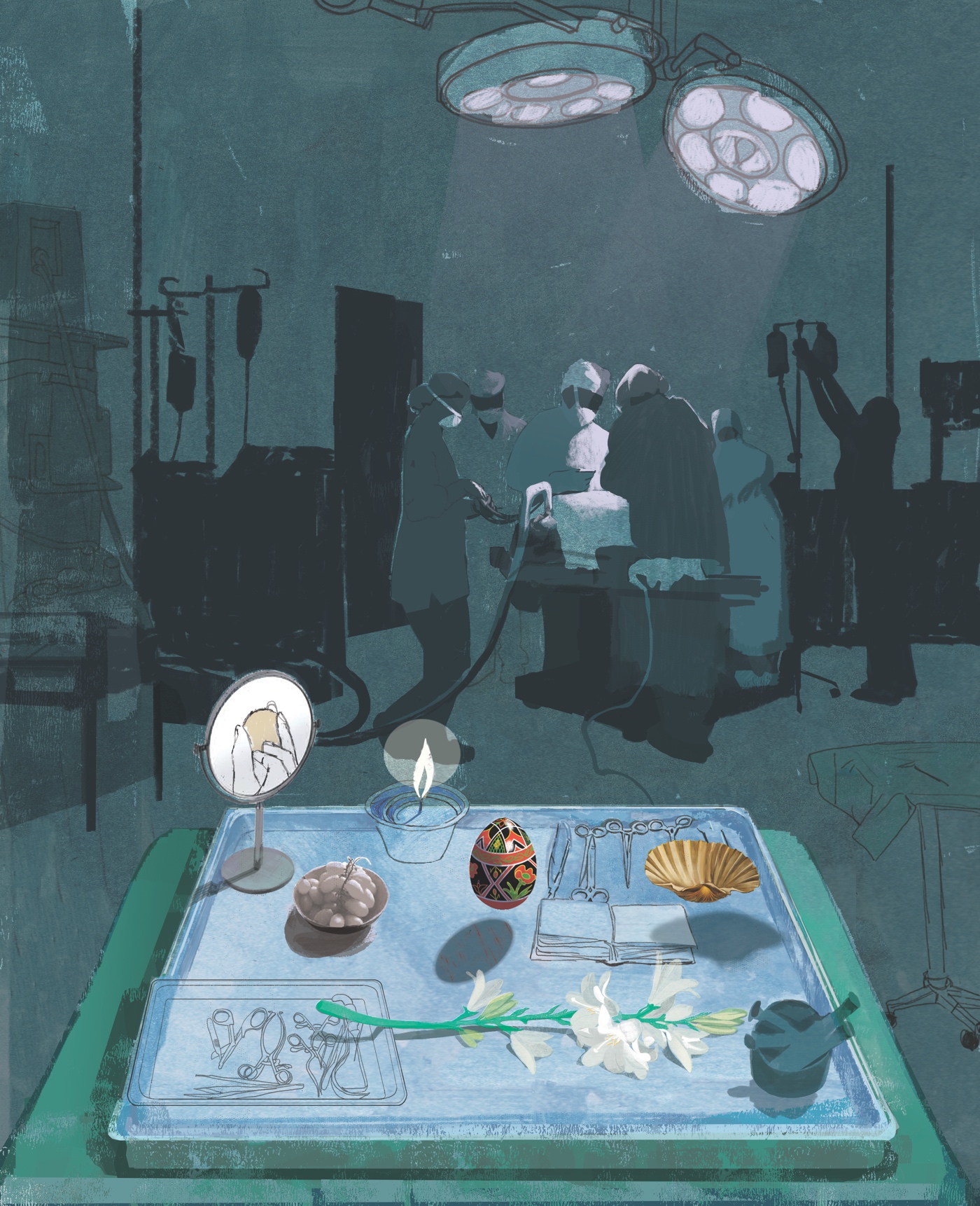

I suspect some of this confusion results from misunderstandings related to the nature of illness and healing, biblical teaching on illness and healing, and the relationship between medical science and Christianity. In this essay, I discuss these issues and consider how a clearer understanding may guide our approach to healing. I argue that the relationship between spiritual and medical healing is not one of either/or but of both/and.

With respect to terminology, I use sickness, illness, and health generically. Note that, although suffering often accompanies sickness, they are not identical, and I am not focusing on this perennial problem. I am also restricting my discussion of Christianity to North American evangelicalism (broadly understood), and of medicine to Western culture. The Greek term pneuma means breath, wind, or spirit and is the root of medical words related to the lungs, such as pneumonia, and of theological words related to the Holy Spirit, such as pneumatology. It provides a handy illustration of the relationship between the two fields.

A COMPLEX CREATION

God’s world is delightful but complicated. Health, its impairment, and its recovery are multifaceted. First, not all illness is bad and most resolves spontaneously. Some afflictions are useful. Pain alerts us that something is wrong or that we need rest. Our bodies heal infections better in a warm environment (i.e., fever is mostly helpful). Also, God designed our bodies to be self-healing—approximately 90 percent of illnesses recover unaided. Healing is likelier when the body is in a state of good nutrition and rest. Doctors don’t heal fractures; they only align the bones so that when new bone grows it heals straight. Antibiotics do not heal damaged tissue. Further- more, medicine is not an exact science and is influenced by changes in research, culture, economics, and politics.

Second, illness development is complex. How we understand causation affects how we respond to events and how much we suffer. Enlightenment philosophy, which views the world in a straightforward fashion, functioning much like a clock, has been influential. This perspective is no longer valid in light of contemporary scientific research:1 Quantum theory suggests that causation can occur at a distance, and chaos-complexity theory tells us that many events, especially biological ones, are dependent on multiple factors that feed back on themselves (causal agents cannot be determined), and that many events that appear to occur suddenly (e.g., water freezing) are actually the result of gradual processes.

The biomedical model of disease dominated medical thought for 125 years. It focuses on pathological processes and treats physical/ biological facets of disease. For example, a bacterium in the lungs causes pneumonia, which is treated with an antibiotic. This “body-as-machine” model is a simple linear one. However, medical science now recognizes that most illnesses are complex dynamic processes; the observed condition (and perhaps its immediate antecedent cause) is only the end result of a web of causation.2 Even genes are affected by the environment. Illnesses are unpredictable; e.g., smoking does not always cause cancer. Furthermore, many disease and treatment mechanisms are unknown. Many conditions (e.g., hyper- tension) occur within a range and “diagnosis” is arbitrary. In addition, medicine recognizes the role of psychosocial factors, such as stress, poverty, and the placebo effect in illness.3 Even the healing of a “straightforward” disease, like pneumonia, depends on the afflicted person’s underlying physical and psychological state.

Along with multiple causes of illness, medicine also endorses multiple treatment approaches. My medical students often only suggest pharmaceutical treatment. However, educating patients about their illness is just as important, as are lifestyle measures such as regular exercise, good nutrition, and adequate sleep. When medication is required, remember that pills are derived from nature (God’s creation). Since many illnesses are self-limited, often physicians take a “watch and see” approach.

In sum, many factors are involved in health and healing; they interact and cannot always be known. If we consider biblical perspectives, we can add sin and evil spirits as causative factors (addressed further below). Sin can be both individual and collective (e.g., environmental pollution), and our sin may not be obvious or directly antecedent to the illness (e.g., the effects of excessive alcohol can manifest long after someone quits drinking). Demons may directly cause illness, but more often piggyback on sin.4 God’s good creation is complex but has been further complicated, and tainted, by human and demonic rebellion.

HEALTH AND HEALING IN THE BIBLE

Biblical conceptions of health are often misunderstood. First, the Bible does not teach that perfect health is an expectation. God pronounced creation “good” but not in a utopian manner.5 Although original creation was untainted by sin, we have no reason to assume that it was free of affliction. In Eden, if the first humans climbed a tree and fell, they would have experienced injuries. The Psalms attest to illness as a universal experience and Paul teaches that suffering is inevitable. This contrasts with a consumeristic culture that demands instant pain relief and a prosperity gospel that expects immediate healing.6 Second, somewhat paradoxically, Christians are not required to suffer. In his earthly ministry and teaching, Jesus never endorsed sickness and suffering, but always worked to heal people. He treats illness as alien, a reflection of a world under the influence of sin and evil.

Third, the Bible depicts healing as all-encompassing.7 Biblical terms for illness, health, and healing reflect the breadth of understanding. Healing in the Old Testament incorporated the ideas of recovery, restoration, peace, forgiveness, and deliverance. Israelites viewed many illnesses as “unclean” and sufferers were excluded from society; therefore, healing had a social dimension. In the Gospels, Jesus heals individuals but emphasizes healing the world, bringing light into the darkness, reconciling humanity with its Creator, and overcoming evil. The Greek terms for health and salvation are closely related. Jesus wants people to have abundant life and restores such life by removing everything that obstructs it, such as physical/mental illness, demonization, and social exclusion (e.g., “unclean” lepers were restored to community once healed). He also instructs his disciples to care for their own health (e.g., avoid drunkenness, Eph 5:18; but occasionally drink a little wine, 1 Tim 5:23) and that of others: He gives the disciples authority to cure sickness (Matt 10:1) and encourages social improvement (Matt 25:31–46). If we restrict the concept of healing to direct divine intervention, we may not notice God’s work in the world.

Fourth, the Holy Spirit may have multiple roles in healing. Medical and spiritual healing are not mutually exclusive. As Christians, we have the indwelling Spirit whose primary activity perhaps is guidance, not just removal of suffering. Our prayers for healing may include direction for self-care and medical decisions, and wisdom for health practitioners. There need not be a sharp divide between natural and supernatural; the Spirit can work through “natural” means and through people of other faiths.

In sum, the Bible views health broadly and assumes neither perfect health nor necessary illness. Physical, mental, and spiritual well-being is desired, though not guaranteed. God heals through our own bodies’ capacities, nature, medical professionals, spiritual communities, and, occasionally, through direct intervention.

CONTEMPORARY MEDICINE AND CHRISTIANITY

As I have implied, medical science and the Holy Spirit can both effect healing, and the latter influences the former. First, science and faith in general are compatible. Although the ancient world viewed them as intertwined, the scientific revolution led to the so-called great divide between science and religion. Fortunately, many scholars now desire discussion between the two.8 Science is a methodology, not a religion. It can explain how, but not why. Most scientists recognize the limits of their discipline. All scientists, regardless of their religion, seek to understand and develop creation. Sometimes science and Christianity have different purposes, but they are not adversaries.

Second, medicine and Christianity are broadly compatible. As mentioned, medicine is moving toward an integrative model that incorporates psycho-social-cultural-religious factors in disease causation and cure. Both medical science and the Bible view illness causation as multifactorial and healing as multifaceted. Contemporary medicine acknowledges the importance of body, mind, and spirit in healing. Indeed, research suggests health benefits from meditation, attendance at religious services, and prayer. Health is being considered broadly—this is closer to biblical conceptions. Medicine increasingly accepts non-material, experiential aspects of healing. As Jesus healed with authoritative words, medicine recognizes the healing power of simple reassurance. I have observed remarkable healing in my psychotherapy work, which primarily uses words. Overall, I believe that medicine and Christianity are increasingly compatible. However, Christianity goes beyond Western medical thought in the following ways: it views all humans, created in God’s image, as worthy; it holds people accountable for their actions and their response to the Creator; and it acknowledges the possibility of interference from evil spirits.

Third, it is our Christian calling to be stewards of creation and cohealers with God. Someone once asked how I could be both a physician and a Christian. Yet I see it as an excellent way to understand creation and to serve our neighbors. I also have a better appreciation of divine sustenance because I am aware of how many factors can impair health. God commands his followers to “rule” the earth (Gen 1:28) and “keep” the garden (Gen 2:15). Jesus teaches us to care for the sick and gives us authority over illness. In a Christian worldview, science is the study of the divinely created order and research findings should be compatible with biblical perspectives. God calls us to image him as cocreators: to care for our own physical, mental, and spiritual health, that of others, and all creation. In sum, medical science and Christianity are not dichotomous; indeed, Christians are commanded to develop and care for creation and to be coworkers in restoring health.

OUR RESPONSE AND RESPONSIBILITY

Sin has separated us from God, ourselves, others, and all creation. Although Christ has overcome sin, we are responsible for continuing the process of reconciliation, or restoring health. As stewards of creation, we are called to understand and heal illness.

First, health, illness, and healing in creation and in the Bible are complex. Medical science recognizes that most afflictions result from multiple factors, including psychosocial ones, interacting; we cannot always identify one specific cause. Medical treatment is also multifaceted. Likewise, the Bible suggests that illness has multiple causes and cures, and healing is multifaceted—intertwined with salvation, deliverance, and social justice. Questions that assume a simple, linear relationship between cause and illness are unhelpful. God does not cause illness, although he may use it for our spiritual development. Although some suffering is inevitable, Jesus always desires health (broadly understood) in his followers. We do not like illness, and simplistic explanations sometimes ease our suffering. Our human need for certainty and control should not hinder our accuracy in understanding. We ought not to avoid responsibility by attributing all illness to external or spiritual agents. We should also take care not to view health too narrowly or idolatrously, and remember that illness never negates our identity in Christ.

Second, medical science and biblical teaching have many areas of overlap and interaction. This makes sense if science is the study of God’s creation. There need not be a dichotomy between professional and pastoral care. We do not have to choose between medical and spiritual healing. God heals in multiple manners: through creation (our bodies’ self-healing capacities and societal discoveries and technologies), through the church (a caring community), and through the Holy Spirit (mostly working through creation and the church, but sometimes directly). Recall that how we understand illness and healing affects our response. This may include a both/ and approach of prayer, healthy behaviors, and medical care. The body of Christ can engage in health education, health research, and healing ministries.

Third, we are all called to care for God’s creation and his creatures. This includes our own health. When we jog, we inhale fresh pneuma; when we pray, we breathe in Pneuma. Recalling the relationship between salvation and healing, we could paraphrase Paul: “Work out your health with fear and trembling for it is God who works in you . . .” (Phil 2:12, 13). When we contract an illness, we can pray for insight, asking whether we need to change any behaviors, confess any sin, or overcome demonic involvement. If our condition requires expert help, we can pray for health professionals. Stewardship also involves care for others. We are to labor with the Holy Spirit to prevent illness, alleviate suffering, and aid healing. This may include offering a friend a kind word, a needed meal, a prayer, or a ride to an appointment. Our healing responsibilities extend beyond the church, including cleaning our environment, feeding the hungry, and clothing the naked.

Sick people may still ask questions, but maybe they will not demand simple answers. The relationship between medical and spiritual healing can be harmonious. Conceptions of illness are wide-ranging but healing is possible, indeed desired, by the one who claims, “I am the Lord, your healer” (Exod 15:26) and who “comforts us in all our affliction” (2 Cor 1:4).