The Balkans represents a geo-political context with a diversity of languages, peoples, cultures, and religions. To the rest of the world, this diversity looks more like complexity, and it is a synonym for political unrest, armed conflict, and most recently, for ethnic cleansing. Historically this region has been a context for power struggles in which different civilizations and empires have tried to claim it for their own realm of influence or control.

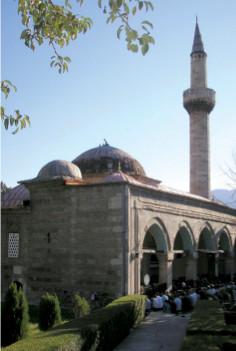

These struggles include religious competition as well. The main religious influences upon the region have been Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Islam. More recently, since the second half of the nineteenth century, the region has witnessed the arrival of Protestant denominations. These have not grown significantly in numbers, but nevertheless have made a considerable impact on the shaping of the religious discourse and the interconfessional landscape. The picture is further complicated by the political transition of the Balkan countries following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Except for Greece and Turkey, the other Balkan countries in the early nineties began the transformation from various communist and socialist systems to political pluralism that inevitably introduced the values of Western secularism and consumerism.

These struggles include religious competition as well. The main religious influences upon the region have been Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Islam. More recently, since the second half of the nineteenth century, the region has witnessed the arrival of Protestant denominations. These have not grown significantly in numbers, but nevertheless have made a considerable impact on the shaping of the religious discourse and the interconfessional landscape. The picture is further complicated by the political transition of the Balkan countries following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Except for Greece and Turkey, the other Balkan countries in the early nineties began the transformation from various communist and socialist systems to political pluralism that inevitably introduced the values of Western secularism and consumerism.

The civil wars that broke out during the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the armed conflicts that nearly rushed Albania into a civil war, the post-Communist loss of governmental trust, and the breakup of the social texture in combination with the unchecked influences of secularism and consumerism had enormous social consequences. The common people were faced with the challenge of adjusting from the previous collectivist mentality, where the individual did not count for much, to the values of individualism—the working ethics of the free market.

Alongside this process, the Balkans saw the rise of religious awakenings in each of the respective traditional religious communities. The traditional Balkan Islam has been evolving into something different under the influence of the current global shifts in the Muslim world. From their side, the Roman Catholic and the Orthodox churches have also been trying to reestablish their role in the position they held before Communism.

Alongside this process, the Balkans saw the rise of religious awakenings in each of the respective traditional religious communities. The traditional Balkan Islam has been evolving into something different under the influence of the current global shifts in the Muslim world. From their side, the Roman Catholic and the Orthodox churches have also been trying to reestablish their role in the position they held before Communism.

Historical reinterpretation and reappraisal of the past is another aspect of the process of transition in the last 20 years. Anachronistic identification between the modern ethnic states and their presumed ethnic ancestors abound. For example, ethnic Albanians claim an unbroken descent from the ancient Illyrians. The contemporary Serbs see the creation of medieval Serbian principalities and kingdoms as the blueprint for modern Serbia. In the same manner, the ethnic Macedonians in the Republic of Macedonia are less inclined to view themselves as descendants of the Slavs, who started arriving in this region from the sixth century AD, and more willing to associate with the Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great as a way of anchoring their national identity, which has been disputed by the neighboring states. As it usually goes in such situations of overlapping history and geography, these processes of ideological identification with one’s (alleged) ancestors often clash with each other.1

The consequence of these clashing claims is to identify the other ethnic and religious groups as the age-old enemy or the oppressor who did great injustice in the past. Such ideological differences were often politically motivated and manipulated and, coupled with the rise of nationalism, resulted in the resurgence of old animosities and conflicts.2

The Communist ideal of “brotherhood and unity,” with its ideology of social equality, integrated all of these separate national identities fairly successfully. As do almost all left-wing ideologies, the ideal emphasized the significance of developing a classless society, for which the main engine was the global working class. As long as the state apparatus remained efficient, this transnational ideology served to submerge ethnic differences.

Religious affiliation was treated by Communism in a similar vein. The international brotherhood and unity of the classless society had little or no space for longstanding religious differences. Seen as a tool of the social elites to subdue and control class struggle, religious differences were removed from the equation for the development of Communism. As a result, numerous communities that practiced a moderate, Turkish-style Islam were suppressed or marginalized. Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant Christian communities shared the same fate of persecution, with the free evangelical churches being more exposed due to their active engagement in evangelism.

That Communism only appeared to be successful in its suppression of religion became obvious soon after its collapse, and forces such as nationalism—which contributed to the downfall of Communism—rediscovered in their respective religious backgrounds strongholds for furthering their nationalistic causes. Nationalism and religion formed strong bonds that perpetuated the myths about the glorious past of pure identities in a supposed golden age.3 These myths furthered the identification of one’s national identity with one’s religious belonging.4 Virtually overnight, the vast majority of the people who emerged from state-enforced atheism took a keen interest in the faith of their ancestors. For Croats this meant reasserting their Roman Catholicism, for Serbs and Macedonians their Eastern Orthodoxy, while Bosniaks and some Albanians with Muslim backgrounds brought forth Islamic beliefs old and new.

This left the evangelical churches in the region facing significant challenges of how to proceed with their respective ministries that are both faithful to the message of the Bible and relevant for the people they aim to serve.

One of the biggest challenges that evangelical churches face in the Balkans is that they are usually seen as a sectarian deviation from true Christianity. As such, they are subversive to society as they introduce foreign concepts that weaken the social and religious fabric, thus weakening the unity of the nation or the ethnic identity. Usually the evangelical churches are blamed for using material and financial aid for the recruitment of members, indicating the thin line between proselytism and genuine evangelism. This is an issue of which evangelical believers have become increasingly aware. They point out that social activism is part of their identity and a major part of responding to Jesus’ commandment to look after those in need. As a consequence, increasing efforts have been made to ensure that any sort of aid will not be used to pressure the beneficiaries regardless of their religious affiliation.

This challenge reveals at the same time the most positive features of the evangelical churches. Generally speaking, as a rule they are not burdened with national identity. Although ethnic and—especially against the Roma—racial prejudices prove to be highly resilient, the only context where interethnic and interracial integration is observable are the evangelical communities.5 Being inspired by the response of the New Testament church and the church in the first three centuries which faced suspicion and opposition, they instinctively took the position of the early apologists and polemicists. These early authors wrote treatises, not to insist on political methods and activism that could provide Christians political and social leverage, but rather to address emperors and governors offering their best arguments to show that the Christians were loyal citizens and did not have any subversive elements that could be a threat to the established political order. In a similar vein, the contemporary free evangelical churches by and large communicated in their sermons, writings, and actions that their utmost social goal was to see their country flourish. It is not surprising then that, among the different faith communities, evangelicals are the most prominent in addressing contemporary social issues such as the role of women in the church, gender equality, substance abuse and addictions, domestic violence, prison ministries, and care for the elderly and other vulnerable groups.

In a comprehensive interview I did with evangelical leaders in the region concerning the issues above, the vast majority asserted that one of the most effective principles of witnessing to Muslims is the fact that, in contrast to the traditional mainline confessions such as Catholicism or Orthodoxy, the evangelical movement is transnational. In the face of growing nationalism and ethnophyletism (the combination of church and state) in the countries of the region, it becomes increasingly obvious that overcoming such forces is essential for the development of Christian witness.

The evangelical churches have a vision for the flourishing of all people in one society that makes it especially sensitive to those whom the Bible identifies as the ones most urgently in need of justice and compassion—the marginalized and the poor. As a way of fulfilling that justice mandate, the evangelical churches have put a special focus on minority outreach and empowerment of the poor. In the context of the Balkans, this is specifically applicable to the Roma, who are usually the most marginalized people group, continuing to live in an isolated and discriminated social subculture. The several vibrant Roma evangelical churches in Macedonia have shown that the good news that Jesus came to preach as announced in Luke 4:18–19 has spiritual and physical dimensions. For example, in the first generation of evangelical Roma believers, the percentage with an education beyond elementary school is virtually zero, while the second generation is catching up with the average population in Macedonia. This is a true paradigm shift in priorities, and much of it comes from the new perspective on life that the Roma get when they convert to Christianity.

The evangelical churches have a vision for the flourishing of all people in one society that makes it especially sensitive to those whom the Bible identifies as the ones most urgently in need of justice and compassion—the marginalized and the poor. As a way of fulfilling that justice mandate, the evangelical churches have put a special focus on minority outreach and empowerment of the poor. In the context of the Balkans, this is specifically applicable to the Roma, who are usually the most marginalized people group, continuing to live in an isolated and discriminated social subculture. The several vibrant Roma evangelical churches in Macedonia have shown that the good news that Jesus came to preach as announced in Luke 4:18–19 has spiritual and physical dimensions. For example, in the first generation of evangelical Roma believers, the percentage with an education beyond elementary school is virtually zero, while the second generation is catching up with the average population in Macedonia. This is a true paradigm shift in priorities, and much of it comes from the new perspective on life that the Roma get when they convert to Christianity.

One of the most significant recent attempts initiated by evangelical leaders of churches and charities is the project “Conversations,” in which representatives from the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Muslim community, and the evangelical community gather together to discuss specific issues from their own religious background as a way of explaining their basic beliefs and tenets to their neighbors of different faiths. The gatherings are structured in a way that promotes mutual respect and allows for each side to explain itself and its beliefs on its own terms. The purpose is to understand the Other rather than to prove one’s view. So far, two such gatherings have been organized, and the feedback has been very positive. This is a grassroots attempt to bring the different communities together as a way of charting paths for long-term development of trust that historically and traditionally has been lacking. The context offered a rare opportunity for each side to be able to explain a major aspect of its belief on its own terms. The topics discussed were the Holy Scriptures in Islam and the being of God in Islam and Christianity.

The work of the evangelical churches in Macedonia in providing a neutral mixing ground for people from diverse ethnic/religious backgrounds has not gone very far. There is a traditional mistrust between Islam and Christianity lasting for centuries combined with the ethnic animosity between the Albanians who live in Macedonia and the ethnic Macedonians. One of the effects of this situation is the almost complete lack of Albanian conversions to Christianity in contrast to the conversion of Albanian Muslims living in Albania and even Kosovo. The past and current evangelistic efforts, including those of foreign missionaries, have not produced any visible results.

In light of what has been said above, it seems that the evangelical churches in Macedonia must first work toward a general change of the interethnic dynamics, and therefore contribute towards the efforts to build mutual trust. Otherwise, the neutral mixing ground that they can genuinely offer will remain locked by the prejudices and stereotypes that have developed among these communities at odds with each other.

This task for the evangelical churches in the Balkans is ever so important and urgent. The aftermath of the wars that begun in 1991 with Slovenia and ended in 2001 with Macedonia have left us with ruptured societies, deepened animosities, and stereotypical corporate memories of the other ethnicity or religion as evil and genocidal.

The evangelical churches have a historic opportunity to set an example of truly integrated communities that can contribute towards the integration of the wider society. To do that they shall certainly continue to preach the two greatest commandments, but they must also be intentional in answering the question “who is my neighbor” and determining practical steps to act upon that answer in the twenty-first-century Balkans.

ENDNOTES

1For an overview of the history of the central and western Balkans, see the relevant chapters in Joseph Held, ed., The Columbia History of Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992).

2An excellent treatment of the Other from a Christian standpoint in the context of former Yugoslavia is Miroslav Volf’s Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Nashville: Abingdon, 1996). For the treatment of the Other from an Islamic standpoint, see Xavier Bougarel, “Islam and Politics in the Post-Communist Balkans, 1990–2000,” in New Approaches to Balkan Studies, ed. Dimitris Keridis, Ellen Elias-Bursac, and Nicholas Yatromanolakis (Dules, VA: Brassey’s, 2003), 345–60.

3For concrete examples of ways in which this coalition was manifested in Serbian and Greek society, see Basilius J. Groen, “Nationalism and Reconciliation: Orthodoxy in the Balkans,” Religion, Church and State 26, no. 2 (1998). See also Ivan Ivekovic, “Nationalism and the Political Use and Abuse of Religion: The Politicization of Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Islam in Yugoslav Successor States,” Social Compass 49 (2002): 523–36.

4Assertions that God and the Croats go hand in hand or that God is a Serb are not new. However, under the influence of violent nationalism, these assertions produced new and sinister consequences as they were literally put into practice in Croatian and Bosnian cities and villages.

5See, for example, the website of The Decade of Roma Inclusion, 2005–2015, a strategic attempt made by NGOs, 12 Eastern European governments, and Roma civil society in an effort to close the huge socio-economic gap existing between Roma and the majority society: http://www.romadecade.org/