Introduction

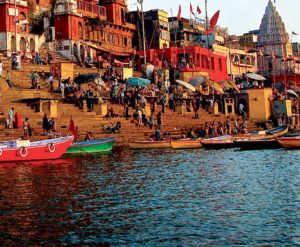

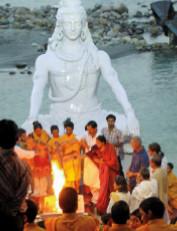

India, often referred to as Bharat or Hindusthan, is a land of plurality, diversity, and complexity. Although India is strongly influenced by Hindu beliefs and practices, it has also demonstrated an amazing sense of tolerance, acceptance, and adaptability with other faiths and religions over the centuries. Historically, there have been occasional clashes between the religious communities, and yet many religions, religious movements, and other faiths have emerged and flourished in India—often tolerating each other and sometimes absorbing certain precepts and practices so as to enrich each others’ spiritual journey.

Christianity in India, though perceived to be a comparatively recent phenomenon, can be traced back to at least the third century, if not to the very first century. The strong tradition of Saint Thomas Christians points to the arrival of the gospel through one of Jesus’s disciples, Thomas, in the first century. Without going into the merits or demerits of this tradition, we can be assured that the Christian faith was present in India long before the emergence of the modern missionary era, prospering for 2000 years alongside the dominant Hindu society. The fact that many forms and practices of Hinduism have been adopted by the Christian community in India is an indication of mutual enrichment and cohabitation.

Christians in India have demonstrated many responses to the dominant Hindu and, to a certain extent, the Muslim, Sikh, and Buddhist communities. Christian perceptions, attitudes, and approaches to each religion range from highly negative to an overtly positive interaction. On the one side, most early missionaries (in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), who were largely products of the Pietistic movement, looked at the native religions as sinful if not Satanic. Hence, their approach to them was more condemnatory. In contrast, particularly in the middle of the twentieth century, a more sympathetic and positive attitude emerged among the Christian missionaries—some of whom even abandoned their missionary vocation and absorbed many religious precepts and practices of the native religions into their own faith. This often led to syncretistic religious practices. However, a large segment of the Christian community in India probably is more inclined to live harmoniously with the people of other faiths, often entering into what we call “informal dialogue” over many central issues of faith and practices. “There are many situations in India where informal dialogue has long been an established reality made possible and often inevitable by the proximity of neighbors of different faiths.”1 This aspect of informal dialogue is part and parcel of their day-to-day life, but apparently has not been taken seriously either by the theologians or church leaders. While this type of informal dialogue perhaps has more potential in making a difference with regard to Christian life and witness in India, sadly very little attention is given to informing, equipping, and mobilizing Christians in India to undertake such informal dialogue with people of other faiths.

Such inattention to the potential found in informal dialogue may have significant consequences since twenty-first-century Christian mission in India will be radically different from that of previous centuries. While acknowledging some damaging and disturbing trends that may have adverse effects on the life and witness of the Christian community, it must not be forgotten that a huge percentage of both the literate and the educated masses are showing signs of openness and positive inclinations towards a deeper and better understanding of Christianity and particularly the person of Jesus Christ. In such a context, it is extremely important to consciously develop positive and constructive ways of establishing a neutral platform from which ongoing dialogue at various levels can be articulated and undertaken. Often it is not the precepts of the Christian faith that are offensive to the people of India; rather, it is the way the Christians present them in their life and practice (or in some instances, fail to practice what they proclaim) that offends people. In the wake of emerging Hindu fundamentalism in India, it is imperative that the Christian community grapple with how to sympathetically interact with people of other faiths so that many misperceptions and misunderstandings can be addressed, thus paving the way for articulating Christian witness in a more constructive manner.

Overview of Essay

Neither theology nor interfaith dialogue is conducted in a vacuum. Cultural and historical dynamics must be studied before attempting to set forward suggestions for Christian witness in a particular context. How is the gospel message heard through the spoken word as well as the lives of Christians? What prejudices and objections first need to be addressed in order to faithfully convey the good news of Jesus? This essay offers a general survey of Christian witness among Hindus in India since the eighteenth-century early modern missionary era in order to orient readers to the challenges and opportunities for Christians to pursue informal dialogue as a means of Christian mission.

The first section of this essay explores an overview of contemporary challenges for Christian mission in India, as well as the corresponding need for new practices and approaches to interaction between Hindus and Christians. Following this, the second section surveys the historical backdrop of Hindu-Christian relations over the centuries. This history continues to impact engagement between these two religious groups today. Of particular importance is the legacy of Western colonialism and its association with Christianity, as well as the debates over the nature of conversion and the implications for understanding Indian identity. The third section offers a summary of significant changes in Christian views of Hinduism during the last two hundred years. Such change in perception has opened up a deeper understanding of Hinduism and enabled Christians to offer a visible witness of the gospel in ways understandable to those in Hindu cultures. The final section of this essay recounts firsthand experiences of interfaith relationships with Hindu scholars and leaders and highlights the possibilities of informal dialogue to create space where the gospel of Jesus can receive an open hearing among Hindus.

The first section of this essay explores an overview of contemporary challenges for Christian mission in India, as well as the corresponding need for new practices and approaches to interaction between Hindus and Christians. Following this, the second section surveys the historical backdrop of Hindu-Christian relations over the centuries. This history continues to impact engagement between these two religious groups today. Of particular importance is the legacy of Western colonialism and its association with Christianity, as well as the debates over the nature of conversion and the implications for understanding Indian identity. The third section offers a summary of significant changes in Christian views of Hinduism during the last two hundred years. Such change in perception has opened up a deeper understanding of Hinduism and enabled Christians to offer a visible witness of the gospel in ways understandable to those in Hindu cultures. The final section of this essay recounts firsthand experiences of interfaith relationships with Hindu scholars and leaders and highlights the possibilities of informal dialogue to create space where the gospel of Jesus can receive an open hearing among Hindus.

I. The Cultural and Religious Landscape of India

The Key Changing Landscapes of Global Christianity2

Throughout the history of Christianity, missiological challenges have always been significant, but how the Church responded to them made the difference. In a sense, the future of Christianity is determined by how well the Church articulates her response to the contemporary challenges, even as the Church itself is radically changing. At the beginning of the twentieth century, approximately 66 percent of all Christians lived in the historical Christian heartland, with 24 percent in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Oceania.3 However, in 2000, David Barrett’s research revealed that the majority of Christians were found in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Oceania.4 He estimated that at least sixty percent of the world’s Christians are now found outside of Europe and North America. Therefore, the reality, perceptions, issues, and challenges of the Christian mission moved from primarily being Euro-America centric to Asia-Africa and South America centric.

India, though still considered a country with a small Christian minority, has emerged as a nation with an increasing number of people claiming to be Christian.5 Even the opponents of the Christian faith in India agree that the number of Christians is increasing in India and they predict that this trend will pick up strong momentum in the near future. 6 In the wake of such predicted changes, Christian mission in India will have to be prepared to face and respond to the challenges in a new and strategic way.

Significant Changes in India

Sociocultural and Economic Changes

While talking about the missional challenges in India, we have to take into consideration the context. With its 4,635 distinct people groups and numerous linguistic groupings, India has been one of the toughest nations in the world as far as evangelization is concerned. With more than two centuries of modern Christian missionary work, we have seen a breakthrough among at least three hundred people groups, primarily among the Dalit (outcastes) and tribal people, but have also seen the reality of India’s resistance to the gospel.7 The stronghold of traditional Hinduism, casteism, Brahminical supremacy, linguistic complexity, and many other issues presented formidable challenges to Christian mission.

However, in recent decades, India has been going through a subtle but certain transformation. This transformation is certainly affecting every aspect of Indian life. With the introduction of the open market economy, the process of globalization has dawned on us and there are sufficient signs that it will stay with us for a long time. Without arguing about the pros and cons of these changes, we are aware of the fact that these are affecting India positively and negatively. The increasing influence of information technology, with its fast and easy modes of communication, has made people aware of what is happening around and beyond their world. India, therefore, is emerging as one of the indisputable powers of the world. Increasing literacy and compulsory primary education significantly adds to the pool of educated and skilled workers. This information explosion coupled with easy global information access makes people aware of the knowledge and opportunities available beyond their traditional boundaries. While regional languages remain important, recognizing English as one of the major languages of communication makes India one of the top English-speaking nations, with the second largest pool of scientists and engineers in the world.8 As India’s population crossed the billion mark, India became one of the youngest nations in the world with regard to the average age of the population. One estimate states that there are more Indians aged 6 to 19 than there are people in the United States.9 All of these, along with many other complex factors, are contributing to the amazing transformation of India.

However, in recent decades, India has been going through a subtle but certain transformation. This transformation is certainly affecting every aspect of Indian life. With the introduction of the open market economy, the process of globalization has dawned on us and there are sufficient signs that it will stay with us for a long time. Without arguing about the pros and cons of these changes, we are aware of the fact that these are affecting India positively and negatively. The increasing influence of information technology, with its fast and easy modes of communication, has made people aware of what is happening around and beyond their world. India, therefore, is emerging as one of the indisputable powers of the world. Increasing literacy and compulsory primary education significantly adds to the pool of educated and skilled workers. This information explosion coupled with easy global information access makes people aware of the knowledge and opportunities available beyond their traditional boundaries. While regional languages remain important, recognizing English as one of the major languages of communication makes India one of the top English-speaking nations, with the second largest pool of scientists and engineers in the world.8 As India’s population crossed the billion mark, India became one of the youngest nations in the world with regard to the average age of the population. One estimate states that there are more Indians aged 6 to 19 than there are people in the United States.9 All of these, along with many other complex factors, are contributing to the amazing transformation of India.

The Transition from Foreign to Indigenous Mission

India is on the threshold of a new era for mission. The post-independence era, beginning from the early 1950s, although considered the sunset for foreign mission, proved a blessing in disguise. The departure of foreign missionaries and structures cleared the way for the Indian church to think through the realities in fresh ways. A significant indigenous missionary movement with hundreds of indigenous missionary societies and thousands of missionaries emerged. A new breakthrough has been reported among different people in various parts of India and especially in the north and northwest of India. What is important to note is that these breakthroughs were reported not only among the traditionally receptive segments that are on the periphery of Indian society, but also the Other Backward Communities (OBCs), and the urban lower and middle classes. Several segments of Indian society previously resistant to the gospel are now showing signs of openness toward the message of Jesus. Several high-caste Hindus—secular but educated and upwardly mobile, from the middle classes—show signs of openness to change. This openness has in some cases turned into receptivity in certain parts of India, resulting in the formation of new churches mostly house churches. Though the authentic number of these churches is yet to be verified, there is some indication that a new and vibrant church is emerging in India among the people once considered nonreceptive.

The Rise of Hindu Fundamentalism

The Rise of Hindu Fundamentalism

However, the increasing influence of Christianity and the growing Christian population have alerted the fundamentalist groups. In some cases, the right-wing political parties together with the fundamentalist groups have brought about systematic persecution and harm upon the Christian community. Cases of severe atrocity have been reported in different parts of India, especially in the areas where the growth of the Christian Church is reported. Several laws and bills have been enacted to prevent conversion to Christianity. Various militant and fundamentalist groups have begun to challenge the spread of Christianity, taking aggressive measures to curtail the increasing influence of Christianity in India. These measures include systematically attacking Christian leaders, demolishing church buildings, intimidation, production of anti-Christian literature, and forceful re-conversion.10 In addition, there is an increase in the production of Hindu apologetic literature aimed to attack Christian faith at an academic level and challenge the foundational beliefs upon which Christianity is built.11 This aggressive fundamentalism is an indication of the growing awareness among the educated caste Hindus about the threat Christianity might pose to their traditional religion.

II. Historical Reactions, Opposition, and Misperceptions of Christianity12

Christianity never had smooth sailing in India. It often faced opposition from different segments of the Hindu community. Opposition from the Hindus was frequently based on partial truths, or no truth at all. Whatever their objections, Hindus found it difficult to understand and accept Christianity as a foreign missionary religion. Numerous misconceptions about Christianity still exist in the minds of the Hindus today.

Christianity: A Western Religion

One of the most often discussed and debated objections to Christianity is that it was introduced to India by Western tradesmen and missionaries, growing “under the pelf and patronage of foreign rulers.”13 To support this argument, many point out that Portuguese and British rulers were instrumental in spreading Christianity in India. The gospel came to India—so most Hindus think—basically through the Western, white colonialists; therefore it has been fiercely opposed by the Hindus as the religion of the imperialists.

Further, Hindus believe that the Portuguese and the British rulers, at least to some extent, were sympathetic toward the Christianization of India. This led to a confirmation of their suspicion that these foreign rulers had been using Christian missionaries for spreading their own religion in India.14 In the minds of the Hindus, Christianity and Western rule went hand in hand. Therefore, to them, becoming Christian meant strengthening the hands of the British in India. This led the Hindus to develop a negative attitude toward Christianity.

Christianity: A Threat to Caste and National Integrity

Historically, conversions to Christianity, especially in central and northern India, brought divisions among Hindu society, castes, and families. By becoming Christian, people sever relationships with their family, caste, and society. They cut themselves off from their own people and relatives. This uprooting from a convert’s social, cultural, and religious traditions is strongly objected to by the Hindus. This allegiance to another social group is perceived to be a threat to national integrity. Staffner is right when he observes that conversion to Christianity is often looked down upon as a social act rather than a spiritual act. It signifies “the change over from one social community to another.”15 When Christianity is perceived to be a dividing factor in the society, it is no wonder that most Hindus shun it.

Under such circumstances, if anybody becomes a Christian, that person is ostracized from the caste and all of their relationships are severed. That person is declared to be an outcaste. Being declared an outcaste, especially for the Hindu, is perceived as a great punishment.16 Such expulsions are considered to be a great social stigma; therefore, rarely does a Hindu take any step that will disassociate oneself from his or her own caste associations. Such persons, in the eyes of the Hindus, have alienated themselves from society, consequently from the nation. By giving allegiance to a foreign religion like Christianity, a person is perceived to have become a threat to national integrity.

The Problem of Conversion

An underlying theme in the above-mentioned misperceptions of Christianity is related to the nature and dynamics of conversion. Specifically, what happens to Indian identity when Christianity is introduced to the life of a person and a community? Is it possible to be Indian without being Hindu, or is there something essential about Hinduism to Indian identity? Questions like these point out the importance of examining some misconceptions about Christian conversion.

Conversion as Unnecessary

Conversion as Unnecessary

Hindu society has never felt comfortable with the idea of religious conversion, and has raised serious objections to it. Conversion is difficult for a Hindu to comprehend. From the standpoint of Hindu religious orthodoxy, it is pointed out that religious conversion is not always genuine and lasting; in any case, it is unnecessary and futile. It is not genuine because Hindus hold that there can be no such radical change in religious convictions as to compel a convert to change over from one religion to another. The Hindu may not question the validity of the conversion experience, but he seriously doubts whether converts from Hinduism to Christianity experience such a total and conscious change of convictions as to take this decisive step of breaking completely away from their ancestral faith—especially because such a migration is unnecessary, according to him.17

One can continue to be a Hindu while believing in other religions; hence there is no need to change religions. Many Hindus admire Jesus as a great teacher, saint and even god, but as one of many gods. To a Hindu “the essential nature of Ultimate Reality is unknowable. It can only be partially apprehended in human experience. Therefore no absolute claims for Truth can be made by any religious community.”18 For the Hindus to acknowledge Jesus as the God and the Savior is to nullify the divinity of the other gods and goddesses of Hindufold. Therefore, “to claim one’s own way as the only right way is seen as spiritual arrogance of the highest order.”19 Change of religion also amounts to looking down on one’s traditional religion, society, caste, and family.

Christians Convert by Unfair Means

For many Hindus the only possible explanation for conversion to Christianity is the unfair means of coercion and persuasion. It is often said that the poor and the needy were the main targets of Christian missionaries, and that these people responded to the welfare programs provided to them. The large percentage of those who became Christians were from the lower or the lowest strata of the society; therefore they are frequently said to have become Christian for material reasons. They are often referred to as “Rice Christians.”

Historically, it can be proven that some Western powers of the eighteenth century encouraged conversions of Hindu subjects by force. Hindus hold that undue pressure, bribes, force, and other unfair means are part of the conversion strategy of the Christian missionaries. So, in the opinion of most Hindus, what Christianity has to offer is only a new materialistic way of earthly living, with added formalities, platitudes, ostentation, and pretension.20

Conversion Defiles

To a Hindu, his religion is pure and holy and admirable. Defecting from it, one becomes impure, polluted, and defiled.21 Hindus perceive Christianity as a religion of lower moral and ethical standards. Therefore, they not only resist conversion but even oppose it.

There are historical reasons for this perception. Julian Saldanha, in his book Hindu Sensitivities towards Conversion, says, “The roots of this opposition to conversion reach back into the mission history of the colonial era and have to do with the manner in which Christianity was introduced in India. The missionaries were identified with the beef-eating, alcohol-drinking foreigners.”22 These foreigners, largely the Portuguese and the British, were in India basically for purposes of trade. Their lifestyle was rarely up to Christian standards. When the Hindus found that these white traders called themselves Christians, they perceived all Christians in the same manner: “It is not surprising that the missionaries and their converts soon came to be called Firangis and Mlenchhas, contemptuous terms connoting barbarians and irreligious persons.”23 Such terms exhibited a certain attitude toward Christianity. This is how most Hindus perceive Christian converts. Thus, Hindus normally keep themselves aloof from such a religion.

Each of these Hindu views of Christianity and objections to conversion must factor in to how Christians interact with their Hindu neighbors. The historical roots of the Christian presence in India do not permit historical amnesia. Christians must identify areas where they sense an openness to the person of Jesus while being mindful of these deep-seated objections and aversions to Westernized Christianity.

III. Christian Attitudes toward Hinduism

There is no single Christian attitude toward Hinduism. Most Evangelical approaches, however, have been based on the assumption that Jesus is the only way of salvation and that all other religions are inadequate in their approach to God. An evangelical attitude has dominated in India.

Evangelical Attitudes

Since most early Protestant missionaries came to India as a result of what is called the Evangelical Awakening, they all had similarities in their assumptions, doctrines, and attitudes. There was a unanimous belief among the Evangelicals that all humankind is fallen due to sin and rebellion against God and therefore is under the condemnation of God. However, through repentance and faith in Jesus, everyone has an opportunity to be saved. Conversion of souls by preaching the gospel was considered to be the primary duty of the missionary in India.

These missionaries often confused the external forms of Hindu religion with its real spiritual message. In the writings of the early missionaries, the evils of the caste system, cow worship, female infanticides, child marriage, and idolatry were often referred to as an inevitable part of Hinduism. Often, practices were misinterpreted or misrepresented by the missionaries. “These very well suited their purpose of showing the moral superiority of Christianity.”24 Their exaggeration was usually done out of ignorance, but occasionally it was also done deliberately.

Missionaries stood firm in their commitment to defuse Christian knowledge, primarily by starting educational institutions, translating the Bible, and publishing books, tracts, and periodicals. However, much of the literature published was polemic in character and reflected their negative attitude toward Hinduism. Vehement criticism of Hindu beliefs and practices was undertaken to expose their evils. Missionaries did everything they could to eradicate the influence and practice of the Hindu caste system. By opening their educational institutions to all castes, they waged war against traditional caste restrictions.

Change in Attitudes

A change of attitude took place gradually among Evangelical missionaries. Several contextual factors contributed in bringing about this change in attitude toward Hinduism. Theologically, a new wave of liberal thinking emerged, which began evaluating Christianity’s unique claims. Additionally, the emergence of Indologists, who presented a less-biased cultural picture, brought to light a brighter side of India and Hinduism. Attempts were made by some Indologists to translate ancient Hindu literature into English. This evoked some enthusiasm among the people of the West. A new look at India as a land of ancient culture, religion, and philosophy began to take shape, forcing many to look at Hinduism more objectively and positively.

Another significant contribution to this shift in views of Hinduism was made by Swami Vivekananda in 1893. His series of lectures on Hinduism at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago aroused great interest in the West. The World Missionary Conference held in Edinburgh in 1910 also played a role in helping shift Christian views of Hinduism. Documents from the conference asserted several positive things about Hinduism and emphasized the need of changing the traditional missionary attitude toward it. As a result, the “older attitude of contempt and hostility toward Hinduism had disappeared from missionary propaganda in India.”25 This new group of Christian missionaries showed more sensitivity toward Hindu culture, religion, and practices. Other religions, including Hinduism, were considered to contain certain elements of truth. Therefore, some began advocating for Christians to engage in interfaith dialogue. A good Christian was expected to listen patiently to what people of other religions were saying. Through this process, it was believed, we may be able to unveil the hidden Christ, who is already present in other cultures and religious communities. Therefore, the responsibility of Christians is to affirm other religions, even to learn from them. People of all religions are considered valuable and credible, since God accepts their devotion as well. This approach took one more step toward a positive understanding of other religions. It has encouraged Christians to seek a fuller and more comprehensive understanding of these religions.

This development of openness to finding and learning from those aspects of goodness and truth in Hindu cultures is a significant shift in Christian witness among Hindus. Nevertheless, this change in perception is good but incomplete. Thoughtful dialogue must take place within the Christian community on how to address the contemporary challenges and opportunities for new forms of interaction between Hindus and Christians. This essay will conclude with a personal example of how I have attempted to navigate these challenges while creatively building on areas where there has been openness to the person and work of Jesus among my Hindu friends.

IV. My Journey towards Informal Dialogue

It was my very first year of church planting and pastoral ministry in the central Indian city of Nagpur. My denomination, Christian and Missionary Alliance, had initiated pioneer church planting ministries in key cities of India, and I was appointed as a fresh seminary graduate to initiate church planting ministry in Nagpur. While our first initiative was primarily focused on the rural migrant workers in the western part of Nagpur, our second initiative proved to be more productive among the educated and medical professional people in south Nagpur. After making some initial contacts with the nurses, paramedics, and dentists in the medical college area, we sensed a need for a place where we could gather regularly for worship services and nurture.

We began to search for a facility and came across an ideal facility that was located right across the Nagpur Medical College. This building belonged to Maharashtra Educational Society, whose president was Mr. Deoba Deotale. He lived in the western part of the city where many elite and upper-caste people made their residence. I made an appointment and went to his residence to meet him and to get permission to use his college building for our worship services. I rang the bell and waited for the response.

Soon the door was opened by a tall middle-aged man. I greeted him and introduced myself. Having heard my name, he looked perplexed because probably he expected a Westernized person with an English name who spoke in broken Marathi. Because I wore Indian kudta, spoke in fine Marathi, and my name was very Indian, he seemed confused as to who I was. He invited me to come inside and asked the reason for my coming. I had already composed myself. So I said, “I am a follower of Jesus Christ”—I purposely did not say that I am a Christian because of its stereotyped connotation. I continued, “I teach the teachings of Jesus Christ to a group of followers of Jesus.” He nodded with positive affirmation. “To provide regular teaching to this group of people,” I said, “I am searching for a hall, and your college hall is an ideal place for us to meet.” I tried to present my case straightforwardly. As I waited for his response, he threw a question at me. He said, “Are you a worshiper of Jesus Christ?” I said “yes.” To my delight and surprise, he said, “I am also a worshiper of Jesus Christ.” This came as a real shock since there was no indication that he was a Christian. He then stood up and invited me to come into the inner room of his house. I was rather hesitant, but followed him into his Puja ghar (worship room); he led me to the center of that small room and, pointing his figure to the framed picture of Jesus Christ, exclaimed, “I just worshipped Jesus this morning.” To prove his point he showed a bunch of fresh flowers offered in front of the picture of Jesus.

That was the beginning of our long friendship. He not only gave me permission to use his college hall for our regular worship services, but also began inviting me to give a series of lectures to his college students about the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. For a number of years, I, along with a team of young people from our church, were invited to present the message of Christmas and Good Friday to the college faculty, staff, and students. On one occasion, he invited me to give a lecture on the biblical view of consuming alcoholic drinks. He also introduced me to his network of Gandhians who regularly meet to reflect on Gandhi’s teachings, which inevitably included the sections from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. On another occasion, he even invited me to address a group of devotees of Saint Tukdoji Maharaj. I deliberately wore a white Indian kudta and pyjama, and I sang Marathi Bhajans (an Indian way of devotional singing primarily used by the Hindus in their temples) and gave a short devotional message on the teachings of Jesus, which were all received reverently by those present.

Over a period of five years that I was in that city of Nagpur, Mr. Deotale became a great friend of mine and spent numerous hours with me discussing informally various aspects of teachings of Jesus Christ. Never once did we argue or fight over our faiths. Through his friendship and contacts, I had numerous opportunities to present the message of Christ to hundreds of his students, staff, and faculty. And as a result, we developed a very cordial and positive atmosphere to listen to each other’s views. This paved the way for me to establish a very positive rapport with a segment of his college faculty and students and provided me a platform to present Christ and his teachings to them in a non-confrontational manner. It must be noted, however, that Mr. Deotale disagreed with me on a few occasions, but because of the kind of rapport and respect we had established with one another, that disagreement never became a point of tension or clash.

Throughout my ministry in Nagpur, I tried to carefully and consciously conduct myself among my Hindu neighbors in ways that did not feed into their stereotypes of Christians and Westerners and certainly not as an attacker who is hostile to Hindu society. Realizing that a large segment of educated urban Hindus are neutral if not sympathetic towards Christ and his teachings, I chose to use that common ground to initiate dialogue and build rapport with them. This required discernment and careful observation, but it was worthwhile in taking the time to discern this and then focus on those who demonstrated a positive orientation towards Jesus Christ. This provided numerous opportunities for me to share Jesus with people who were open and neutral towards Christianity. Often this allowed them to ask pertinent questions about Jesus and his teachings, and my response to such queries was also received positively. It left behind a positive impact and to a large extent changed their stereotyped perceptions about Christ and Christianity. Through this I learned a very valuable insight: never assume that all Hindus or people of other faith are hostile towards Christ and Christianity; rather, most of them are quite open to hearing about the gospel—if presented in a more informal and non-confrontational manner.

Today, Indian Christians—and especially Evangelical Christians—have a great opportunity to develop a non-confrontational dialogical approach to mission that creates a more positive atmosphere and cordial relationships with people of other faiths, in order to communicate the message of Jesus Christ effectively.

Endnotes

1Bob Robinson, “Christian-Hindu Dialogue – Are There Persuasive Biblical and Theological Reasons for It? A Critical Assessment,” Dharma Deepika 24 (10), January–June 2006, 10.

2Atul Aghamkar, “Contemporary Mission Challengesin India,” paper given at the Center for Missiological Challenges in India,” paper given at the Center for Missiological Research Colloquium at Fuller Seminary, Pasadena, CA, Spring 2011.

3Wilbert R. Shenk, “After Bosch: Toward a Fresh Interpretation of the Church in the Twenty-First Century,” UBS Journal 2, no. 2, September 2004, 8.

4David Barrett and Todd Johnson, “Annual Statistical Table on Global Mission,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 22, no. 1 (January 1998): 2627.

5A. P. Joshi, M. D. Srinivas, and J. K. Bajaj, Religious Demography of India (Chennai: Centre for Policy Studies, 2003).

6Such predictions are based on the data collected from census reports, contemporary trends, and the socioreligious moods of people.

7Although there seems to be no consensus as to how many people groups have been reached with the gospel thus far, looking at the traditional and contemporary breakthroughs among specific people, the estimated number could easily come to about 300.

8Thom Wolf, “The Wrinkled/Wired Elephant: Firsts, Facts and Facets of India,” paper presented at New Delhi on February 23, 2005.

9Anand Giridhardas, “In India Some Don’t See Billion as Too Many,” International Tribune Herald, May 4, 2005.

10Dasarathi Swaro, The Christian Missionaries in Orissa: Their Impact on Nineteenth Century Society (Calcutta: Punthi Pustak, 1990); Angana P. Chatterji, Violent Gods: Hindu Nationalism in India’s Present; Narratives from Orissa (Gurgaon: Three Essays, 2009); Prafulla Das, “VHP, Bajrang Dal Men Storm Orissa Assembly,” The Hindu (17 March 2002); “VHP Orchestrates Mass Reconversion in Orissa,” Deccan Herald (2 May2005).

11Arun Shourie, Missionaries in India: Continuities, Changes, Dilemmas (New Delhi: ASA Publications, 1994); Arun Shourie, Harvesting Our Souls: Missionaries, Their Design, Their Claims (New Delhi: ASA Publications, 2000); Sitaram Goel, History of Hindu-Christian Encounters, AD 304 to 1996 (New Delhi: Voice of India, 1996); Sita Ram Goel, Catholic Ashrams: Sanyasins or Swindlers? (New Delhi: The Voice of India, 1988); Shripaty Sastry, A Retrospect Christianity in India (Pune: Bharathiya Vichar Sadhana, 1983); Subramanian Swamy, Hinduism under Siege: The Way Out (New Delhi: Har-Ananda, 2006).

12Atul Y. Aghamkar, “Traditional Hindu View and Attitudes toward Christianity,” Global Missiology English 2, no. 5 (2008), http://ojs.globalmissiology.org/index.php/english/article/view/244.

13Ebenezer Sunder Raj, The Confusion Called Conversion (New Delhi: TRACI, 1986), 2.

14Paul D. Devanandan, “Modern Hindu Attitude toward Christian Evangelism,” Union Seminary Quarterly Review 12, no. 3 (1957): 65–80.

15Hans Staffner, The Open Door (Bangalore: Asian Trading Corporation, 1987), 63.

16Julian Saldanha, Hindu Sensibilities towards Conversion (Bangalore: Asian Trading Corporation, 1981), 9.

17Devanandan, “Modern Hindu Attitude toward Christian Evangelism,” 68.

18Paul D. Devanandan, Preparation for Dialogue: A Collection of Essays on Hinduism and Christianity in New India (Bangalore: Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society, 1961), 7.

19Newton H. Malony and Samuel Southard, eds., Religious Conversion (Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press, 1992), 13.

20K. V. Paul Pillai, India’s Search for the Unknown Christ (New Delhi: FAZL Publishers, 1979), 167.

21A person who leaves the Hindu fold and joins another religion is normally considered an outcaste and thus polluted and defiled.

22Saldanha, Hindu Sensibilities, 4–5.

23Saldanha, Hindu Sensibilities, 5; cf. Pillai, India’s Search, 167.

24Sushil Madhav Pathak, American Missionaries and Hinduism: A Survey of Their Contacts from 1813 to 1910 (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharial Oriental Publisher, 1967), 81.

25Pathak, American Missionaries, 235.