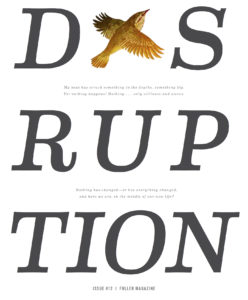

+ Years after its founding, Fuller’s campus moved to the location where it would spend the next seven decades. Above, bulldozers demolish part of Oakland Avenue to create Arol Burns Mall and what became affectionately known as “the Elbow,” the unofficial entrance into Fuller Seminary’s Pasadena campus at the corner of Oakland and Ford Place.

Disruption is not new to Fuller: the ethos of the seminary has been influenced by it throughout the life of the institution, from its beginning. While maintaining an unswerving commitment to the gospel of Jesus Christ, the intention to become a convening place of different points of view has built Fuller into the largest multi-denominational seminary in the world. Fuller’s trajectory has widened in 70 years from a small set of distinctions to an increasing diversity of denominations, countries, theological perspectives, inclusion and equity for women and persons of color, and more. This, in the ongoing intention to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly in our pursuit of knowing God.

Perhaps the most pronounced of these disruptions—the decision to move Fuller’s campus to Pomona—was set in motion by the Board of Trustees after much deliberation on May 21, 2018, when the vote was confirmed to sell the historic Pasadena campus. At that meeting, a poem by Wendell Berry was read that compares the life of faith to walking toward the sun: a light so bright that it obscures and reveals. Looking back, “the very light that blinded us shows us the way we came,” the poet says, orienting us toward an unknown future. We, “by blessing brightly lit, keep going toward / The blessed light that yet to us is dark.” That dual movement between uncertainty and grace is familiar territory to Fuller.

Looking backward can stabilize concerns about a future we could not have anticipated. By remembering the vision and risk, passion and mistakes, joy and courage of those who have given their lives to building the seminary, we can see the grace that lit their own steps—and ours in this new season. It is in this spirit that we begin this issue on “disruption.” On the following pages you’ll find three letters from President Mark Labberton, originally posted online at fuller. edu/future, that discuss the seminary’s future and decision to move to Pomona. Interwoven with these are brief memories of a few critical moments in Fuller’s history, to remind us that, as we take this next faithful step, we must follow an institutional tradition of facing disruption with creativity and conviction.

Founding the School

+ Fuller Seminary’s founding faculty and leadership stand at the Cravens Estate, the original site planned for the campus. Left to right: Harold John Ockenga, Charles E. Fuller, Everett Harrison, Harold Lindsell, Wilbur Smith, Arnold Grunigen, Carl Henry (c. 1947)

With a passion to train people “to become steeped in the Word, so as to go out bearing the blessed news,” Old Fashioned Revival Hour radio broadcaster Charles E. Fuller—through his Fuller Evangelistic Foundation— purchased the Cravens estate on Pasadena’s “Millionaire Mile” in 1947 for a new seminary. He promoted Fuller Seminary on his radio program and enlisted faculty from around the nation. When the city refused to change the zoning to allow teaching at the Cravens estate, Charles’s son, Dan Fuller, stood at its driveway entrance on the morning of the first convocation, directing the 39 new students to Lake Avenue Congregational Church where classes were held for the next six years. “We members of that first class will never quite forget the incongruity of hearing Carl Henry’s insights into the theory of religious knowledge while sitting on kindergarten chairs,” Dan remembers (Give the Winds a Mighty Voice, 208). It wasn’t until 1951 that the seminary bought new property a few blocks east of Pasadena City Hall where, as President Harold John Ockenga put it, the seminary could operate “in the midst of the throb and tumult of this teeming life” (Reforming Fundamentalism, 131).

Founding a School of Psychology

+ The Pasadena Community Counseling Center (pictured c. 1964) was the precursor to the School of Psychology. In 1986, the school received its own home on the corner of North Oakland and Walnut, with the relocation of Stephen Hall and construction of Travis Auditorium and the School of Psychology building.

“Black Saturday could be called Good Saturday,” H. Newton Malony, professor emeritus of psychology, says, since on that 1962 day Fuller’s trustees also decided to pursue establishing a school of psychology (Psychology and the Cross, 15). Yet some theology faculty argued that importing an entirely new discipline through the new school would distract students from confessional faith and the life of the church. The proposed school also uncovered new thorny questions of how to understand the connective tissues between psychology and theology. Some believed that Fuller should promote an “overlay” approach, with students taking psychology classes at a neighboring school and overlaying a theological framework from seminary courses. Others suggested a unique “theo-psychology” that could replace psychology as an academic discipline. Still others suggested an integration model that would emerge as faculty and students wove their Christian commitments and therapeutic practices together—an approach that disrupted churches who were suspicious of therapy and an academic discipline often dismissive of faith. Siding with this third way, President Hubbard said, “We must launch this school on a scope of largeness,” and in 1964–1965, with the vital support of C. Davis and Annette Weyerhaeuser, the Pasadena Community Counseling Center followed by the School of Psychology were established, founded on a principle of thoughtful integration that continues today.

Changing the Name of the School of World Mission

+ Charles Fuller announces the launching of the School of World Mission in 1965.

After September 11, 2001, Fuller’s School of World Mission was becoming more passionate about interfaith dialogue and engaging the Muslim world. “We were expanding our efforts in this area since it was of such global importance,” Doug McConnell, the dean at the time, remembers. At the same time, changes in government policies and visa requirements made it difficult for the school’s alumni to reach the communities where they were called to minister, and countries wary of foreign influence would deport them as soon as they saw the words “World Mission” on their diplomas. In many cases, alumni faced threats to their lives, and in one instance, an alum was encouraged to start a training institute in an Arab country, only to have it revoked when he submitted his credentials and given 24 hours to leave. Changing the name of the school was both a way to respond to the changing world, and part of an unexpected identity crisis. After many months of faculty gatherings and deliberations, the school reached a decision to change its name to the “School of Intercultural Studies” in 2003. Many graduates were elated and asked for ways to change their diplomas; others felt the name change would erode the mission of the school. “We felt like we needed a name that would engage with the social contexts that people were going into,” McConnell remembers. “It was an adaptive change to the world we live in.”

Debate Over Biblical Authority

+A Fuller student exits Payton Hall, c. 1972–1979. (Recognize him? Email us at [email protected]!)

With political and theological issues pressing in on all sides, the trustees’ “ten-year planning conference” of December 1962 quickly fractured into what is now known as “Black Saturday.” For years, debates about scriptural inerrancy and the identity of the next resident president fomented, boiling over in this trustee meeting into a struggle for the seminary’s future. With President Harold Ockenga leading in absentia from Boston and David Allan Hubbard under scrutiny for coteaching a Westmont College class that didn’t square with Fuller Seminary’s prevailing fundamentalism, the presidential candidates and views of Scripture aligned into two distinct camps. After bitter arguing—so heated that one trustee walked out and never returned—Ockenga was chosen, but soon after, a “mystical experience” led him to step down. Hubbard became president by default, faculty and trustees left in the fallout, and the debate on scriptural inerrancy at Fuller continued—to the point that founding faculty member Harold Lindsell wrote a scathing chapter on the seminary in his 1976 book Battle for the Bible. Hubbard responded with a special issue of Theology, News and Notes, clarifying Fuller’s position regarding Scripture as “the only infallible rule of faith and practice.” Hubbard wrote, “None of us denies the infallibility of the Bible; none of us claims the infallibility of our faculty. We are not perfect. We do not have to be. We have God’s sure word to guide and correct our steps; we have Christ’s sure grace to forgive our errors; we have the churches’ continued goodwill as, for the glory of God, we fulfill our mission and theirs.”

Demands for the Inclusion of Women

+Fuller students enjoy the Arol Burns Mall, c. 1972–1979. (Recognize them? Email us at [email protected]!)

On April 26, 1976, six women staged a two-day sit-in at Provost Glenn Barker’s office to pressure the seminary to support female students in a more direct way. While women could attend some seminary courses as early as 1948 and had gained increased access to degree programs over the following years, by the mid-1970s, women were still vastly underrepresented across the seminary community. Looking back on the sit-in, participant Karen Berns (MDiv ’84) says, “Today we have an illustrious panoply of women faculty at Fuller. Then, we were looking for full time, tenure-track women faculty in the School of Theology as there were none at that time and for a new office that could be a nurturing advocacy for women’s students. We weren’t going to leave Dr. Barker’s office until there was action toward that,” she remembers. “It was not a tense experience for me, and he was amenable to what we were demanding. We stayed until we heard from him that this was going to happen.” Soon after, the seminary responded by establishing the Office of Women’s Concerns under the leadership of Libbie Patterson. Only two years later, the seminary and the Evangelical Women’s Caucus co-sponsored the “Women and the Ministries of Christ” conference that over 800 women from around the world attended. “We made it clear that women are welcome, and they started to show up,” the late trustee Max De Pree remembers. “That was a great message to the church. If you were a woman and you felt called to ministry, you could go to Fuller.”

Collision of Theological Views

+ A Los Angeles Times story covers the height of the campus controversy, 1986.

In 1982, when C. Peter Wagner, professor of church growth, began teaching the course “MC510: Signs, Wonders, and Church Growth,” with the assistance of John Wimber, a founding leader of the Vineyard Movement, the class had a simple format: the first half was for lectures on the biblical and theological foundation for miracles, and the second was devoted to an optional “ministry time” where teachers and students alike would be prayerfully open to the Holy Spirit in their midst. The class grew rapidly as reports of healings, speaking in tongues, and exorcisms spread through campus. “It became so popular we had to post people at the door to keep out those who were not enrolled,” Paul Pierson, then-dean of the School of World Mission, says. “I even got calls from people asking if they would be healed if they went to the course. It became very sensational, and it was perceived as unhealthy by some.”The School of World Mission faculty voted to discontinue the course to avoid further tension with the theology faculty, and, and a task force was created to reflect on its theological, psychological, and missiological implications. Wagner later recalled: “During the first few meetings emotions were high. Fear, anger, suspicion, skepticism, and even distrust were evident. But all was bathed in prayer” (Signs and Wonders Today, 8–9). The topics of the Signs and Wonders class were eventually integrated into other courses. “I really believe that missiology gained when we opened the door to the fact that God does things that go beyond our normal way of thinking,” Pierson remembers. “Renewal always starts on the periphery and never in the center. The Holy Spirit is not done with his creativity—he still has a lot up his sleeve!”

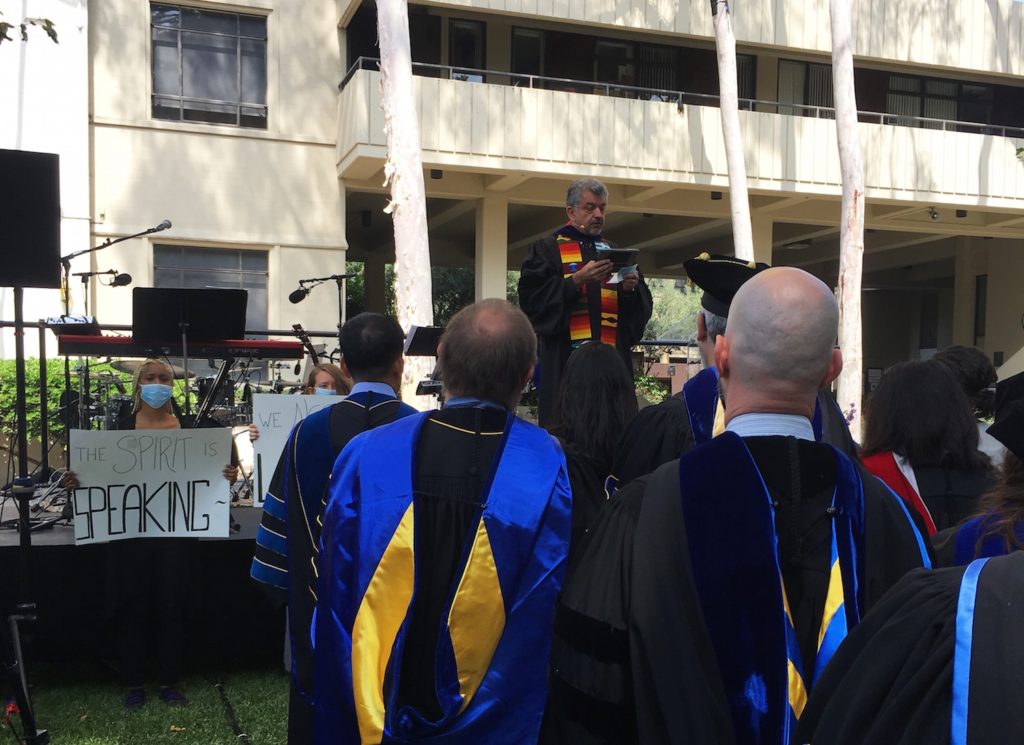

Protest for Inclusion and Equity

During Fuller’s 2018 Baccalaureate service, a group of students and alumni emerged from the prayer garden wearing surgical masks, pulling IV bag stands, and holding signs protesting racial inequality they had experienced at the seminary. Juan Martínez, professor of Hispanic studies and pastoral leadership, members of the chapel team, and other faculty members also wore masks while students stood throughout the audience for the rest of the program. As the service continued, the speakers acknowledged and received the protest, embodied in the call and response at the close of the service: “The Spirit is speaking” and “We need to listen.” The protest was a difficult disruption for some, a galvanizing moment for others, and a clear call to action for the leadership of Fuller. It illustrated the depth of disappointment among many Black students at Fuller, intolerance for “just words” that might prove empty, and demands for change. “Today’s protest at Baccalaureate was a ‘painful gift’ that bears witness to injustice suffered by our African American students,” said President Mark Labberton. “We are at a crossroad: Change must happen.”