In the beginning was the word in The French Dispatch, Wes Anderson’s long release-delayed ode to the literary magazine ideal and the commitment to artistry that both informs and sustains publications like The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and The Paris Review. Anderson’s fictional literary magazine was started many years ago when a Kansan in need of a more well-rounded worldview ended up in Ennui, France—I laughed out loud every time the film reminded me of the name of Anderson’s fictional French burg—on a holiday that never ended.

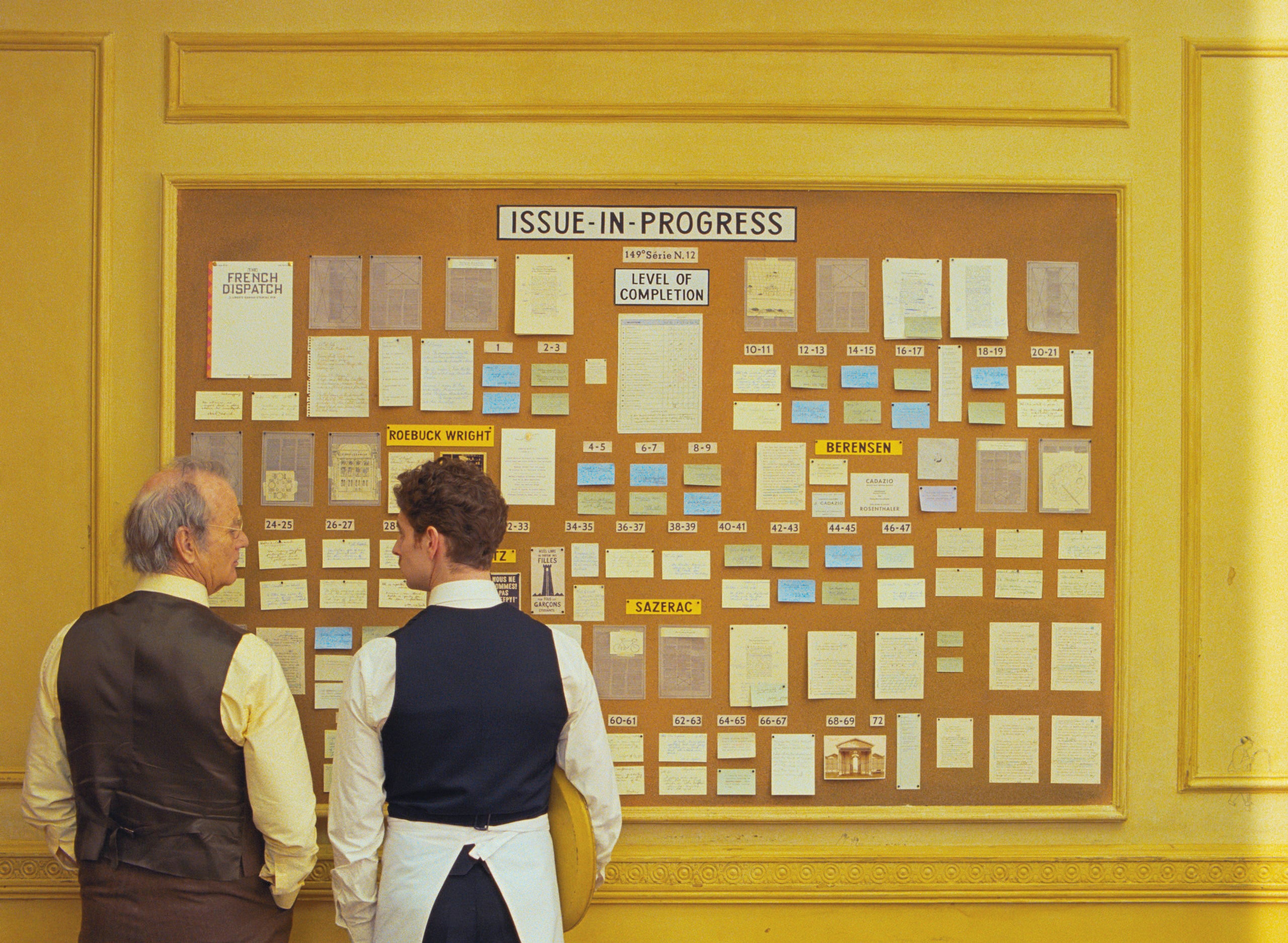

Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (a barely seen Bill Murray) began sending home missives about Ennui life for his publisher father’s readers. He gathered a few more American literary minds around him in the ensuing years, folks with a similar commitment to the majesty of the written word, and kept the publication humming along until his death. The French Dispatch is a sorta anthology film of little stories gathered on the occasion of Howitzer Jr’s death, as if we are reading the final issue of the titular magazine. So there is a touch of sadness to this record of happenings in Ennui. It is a memorial to the glory of the way things were and will not be again.

Nostalgia has long been a key element of Anderson’s films. Then are soaked in 1960s and 70s cinematic conventions and music. Anderson moves fluidly between visual styles in The French Dispatch, covering French New Wave verve, Filmnation animation styles, Jacques Tati’s kind of composed-frame comedy, and Anderson’s favored Rankin/Bass-inspired stop-motion techniques. The general temperament of his characters has always been that of someone who read Dale Carnegie or David Schwartz when they were young and are disappointed that merely believing you can isn’t enough to make the world be as you want it to be – late-60/early ‘70s disillusionment played on an minor key calliope.

Howitzer Jr. and his staff’s dogged commitment to their artistic ideals—a commitment we see echoed in the characters in the stories they tell—as well as, perhaps, their willingness to be estranged from their home—all the artists in their stories are also alienated in one form or another—is perhaps all that sustains their art. It’s a sobering assertion for those of us engaged in literary pursuits, but perhaps it’s a tonic we need as the literary industry is being hollowed out from the inside.

When all the people on staff at The French Dispatch finally gather together, we want to be in that room. There is no greater tribute to their editor’s life and work than their continued work even in his absence. We are not really allowed to be in that room though. Creative communities don’t really allow for onlookers. You have to sink your hands into the materials and get to work. So The French Dispatch may not be circulating any longer, but that doesn’t mean we can’t still gather and create. In the beginning was the word, and the word will persist in one form or another, as long as we keep speaking it, or, in this case, writing it. No darkness, not even the darkn

In the beginning was the word in The French Dispatch, Wes Anderson’s long release-delayed ode to the literary magazine ideal and the commitment to artistry that both informs and sustains publications like The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and The Paris Review. Anderson’s fictional literary magazine was started many years ago when a Kansan in need of a more well-rounded worldview ended up in Ennui, France—I laughed out loud every time the film reminded me of the name of Anderson’s fictional French burg—on a holiday that never ended.

Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (a barely seen Bill Murray) began sending home missives about Ennui life for his publisher father’s readers. He gathered a few more American literary minds around him in the ensuing years, folks with a similar commitment to the majesty of the written word, and kept the publication humming along until his death. The French Dispatch is a sorta anthology film of little stories gathered on the occasion of Howitzer Jr’s death, as if we are reading the final issue of the titular magazine. So there is a touch of sadness to this record of happenings in Ennui. It is a memorial to the glory of the way things were and will not be again.

Nostalgia has long been a key element of Anderson’s films. Then are soaked in 1960s and 70s cinematic conventions and music. Anderson moves fluidly between visual styles in The French Dispatch, covering French New Wave verve, Filmnation animation styles, Jacques Tati’s kind of composed-frame comedy, and Anderson’s favored Rankin/Bass-inspired stop-motion techniques. The general temperament of his characters has always been that of someone who read Dale Carnegie or David Schwartz when they were young and are disappointed that merely believing you can isn’t enough to make the world be as you want it to be – late-60/early ‘70s disillusionment played on an minor key calliope.

Howitzer Jr. and his staff’s dogged commitment to their artistic ideals—a commitment we see echoed in the characters in the stories they tell—as well as, perhaps, their willingness to be estranged from their home—all the artists in their stories are also alienated in one form or another—is perhaps all that sustains their art. It’s a sobering assertion for those of us engaged in literary pursuits, but perhaps it’s a tonic we need as the literary industry is being hollowed out from the inside.

When all the people on staff at The French Dispatch finally gather together, we want to be in that room. There is no greater tribute to their editor’s life and work than their continued work even in his absence. We are not really allowed to be in that room though. Creative communities don’t really allow for onlookers. You have to sink your hands into the materials and get to work. So The French Dispatch may not be circulating any longer, but that doesn’t mean we can’t still gather and create. In the beginning was the word, and the word will persist in one form or another, as long as we keep speaking it, or, in this case, writing it. No darkness, not even the darkn

Elijah Davidson is Co-Director of Brehm Film and Senior Film Critic. Find more of his work at elijahdavidson.com.

No Time to Die is an admirable farewell for Daniel Craig’s take on Bond. The movie is maybe a little long, but it’s long in the way that a dinner with friends stretches into the evening when you don’t really want it to end.