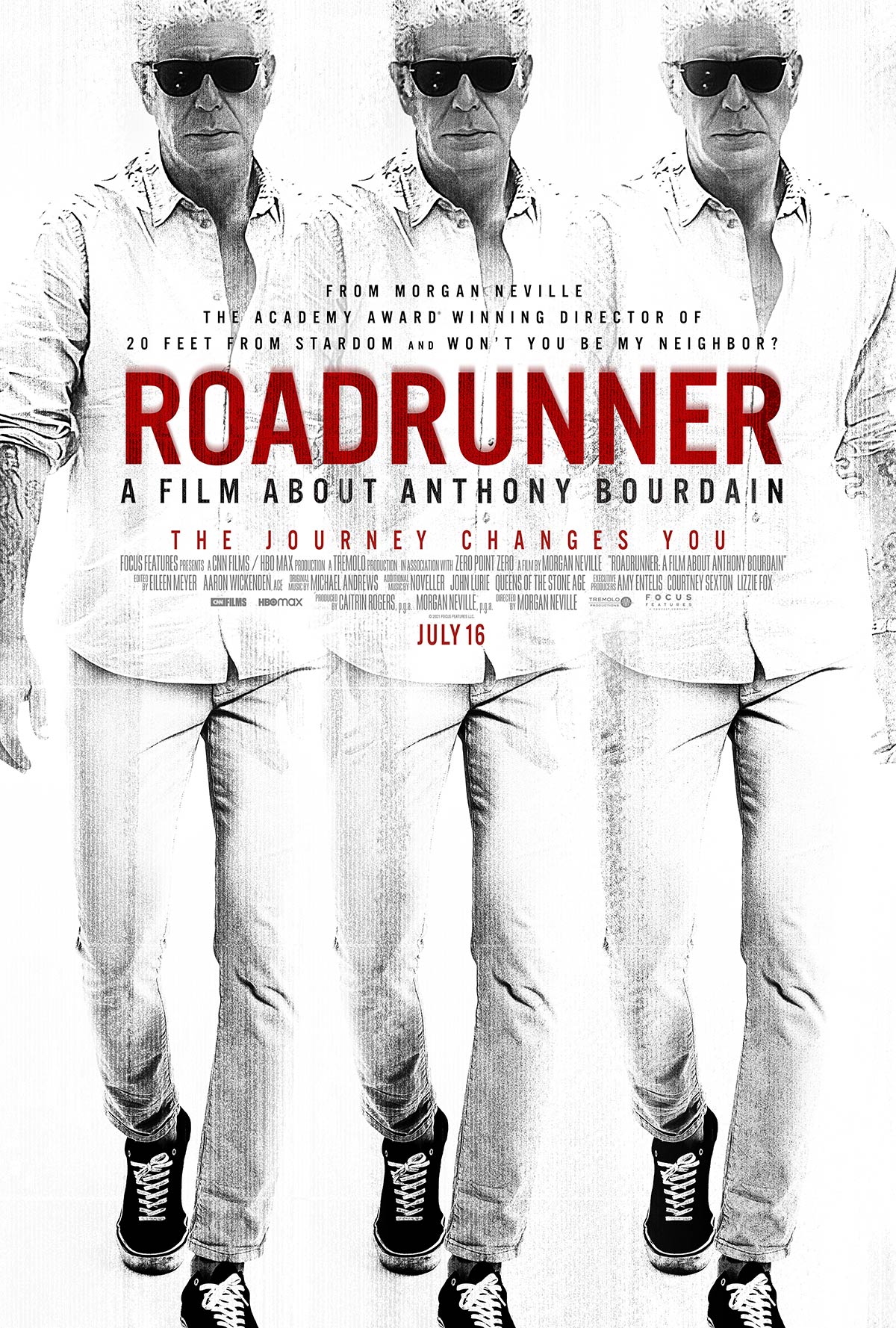

Anthony Bourdain committed suicide on June 8, 2018, by hanging himself in a hotel room in France. Though he had a well-known history of substance abuse—he’d been free of heroine for thirty years—toxicology reports stated that he was perfectly sober at the time of his death. If you are interested in this new documentary about his life, Roadrunner, from documentarian Morgan Neville, you are likely aware of these facts. Bourdain was famous, most of all, for his candidness in all things. Unlike almost everyone, he didn’t seem to see a reason to hide anything he thought, felt, or did in his life. “Confidential,” as in disclosure, was even in this title of his best selling book.

Death is the end of almost every story. We know the curtain will eventually fall on us all. There is mystery beyond the veil. Suicide is as if the performer grabs the curtain, rips it from its runners, wraps it around himself, and disappears. Suddenly, mystery is forced on the audience out of step with the story we thought we were watching. It is always a cataclysm. In Bourdain’s case, given his lifelong practice of full disclosure, it feels exceptionally non sequiter. There’s the challenge of the film. On the one hand, if ever we are going to understand a suicide, it might be Bourdain’s since he told us everything about himself, we think. On the other hand, the death is so out-of-step with Bourdain’s televised and published reality, making sense of it might be as impossible as explaining whatever the opposite of a miracle is.

Still, Morgan Neville tries. Roadrunner is structured as a biopic using the copious amounts of material Bourdain recorded and wrote over the years. Bourdain’s friends, family, and production partners comment on the events of “Tony’s” life. It’s as if they are watching what we are watching. Neville and editors Eileen Meyer and Aaron Wickenden even edit the film as if the interview subjects are looking at the footage. Everyone is trying to make sense of Bourdain’s life and death.

If you’ve ever had a loved one commit suicide, you know that this is ultimately an impossible task. One of the bruising lessons of suicide is that it confronts us with the knowledge that we cannot know someone completely. It feels as if we didn’t know them at all, and now we never can. There are some injustices, some tragedies, some wrongs and evils in life that we will never comprehend.

Roadrunner knows this. Right in the middle of the film, the interview subjects recount an experience Bourdain and his crew had in Beirut while filming an episode of No Reservations in 2006. They find themselves in the midst of war. They escape with other refugees. They see the horrors of war. Bourdain’s work, ostensibly, is traveling the world, meeting people, eating their food, and transcending boundaries. The work is guided by a belief that the table is the great leveler. Bourdain’s experience in Beirut qualifies that faith. Some evil seems insurmountable. Bourdain refused to neatly package that experience for television.

Roadrunner resists the urge to neatly package Bourdain’s life and death as well. It is a bold move, in accord with Bourdain’s example, and it’s undercut only slightly by the statement that this is what “Tony” would have wanted. If the preceding two hours had taught us anything, it’s that we shouldn’t presume about what Anthony Bourdain desired. He thrilled to challenge the expectations of everyone he loved, worked with, and entertained. Like all of us, we are fully known not even to ourselves. We are known fully only to the One we meet beyond the veil. I pray Tony was well met.

Anthony Bourdain committed suicide on June 8, 2018, by hanging himself in a hotel room in France. Though he had a well-known history of substance abuse—he’d been free of heroine for thirty years—toxicology reports stated that he was perfectly sober at the time of his death. If you are interested in this new documentary about his life, Roadrunner, from documentarian Morgan Neville, you are likely aware of these facts. Bourdain was famous, most of all, for his candidness in all things. Unlike almost everyone, he didn’t seem to see a reason to hide anything he thought, felt, or did in his life. “Confidential,” as in disclosure, was even in this title of his best selling book.

Death is the end of almost every story. We know the curtain will eventually fall on us all. There is mystery beyond the veil. Suicide is as if the performer grabs the curtain, rips it from its runners, wraps it around himself, and disappears. Suddenly, mystery is forced on the audience out of step with the story we thought we were watching. It is always a cataclysm. In Bourdain’s case, given his lifelong practice of full disclosure, it feels exceptionally non sequiter. There’s the challenge of the film. On the one hand, if ever we are going to understand a suicide, it might be Bourdain’s since he told us everything about himself, we think. On the other hand, the death is so out-of-step with Bourdain’s televised and published reality, making sense of it might be as impossible as explaining whatever the opposite of a miracle is.

Still, Morgan Neville tries. Roadrunner is structured as a biopic using the copious amounts of material Bourdain recorded and wrote over the years. Bourdain’s friends, family, and production partners comment on the events of “Tony’s” life. It’s as if they are watching what we are watching. Neville and editors Eileen Meyer and Aaron Wickenden even edit the film as if the interview subjects are looking at the footage. Everyone is trying to make sense of Bourdain’s life and death.

If you’ve ever had a loved one commit suicide, you know that this is ultimately an impossible task. One of the bruising lessons of suicide is that it confronts us with the knowledge that we cannot know someone completely. It feels as if we didn’t know them at all, and now we never can. There are some injustices, some tragedies, some wrongs and evils in life that we will never comprehend.

Roadrunner knows this. Right in the middle of the film, the interview subjects recount an experience Bourdain and his crew had in Beirut while filming an episode of No Reservations in 2006. They find themselves in the midst of war. They escape with other refugees. They see the horrors of war. Bourdain’s work, ostensibly, is traveling the world, meeting people, eating their food, and transcending boundaries. The work is guided by a belief that the table is the great leveler. Bourdain’s experience in Beirut qualifies that faith. Some evil seems insurmountable. Bourdain refused to neatly package that experience for television.

Roadrunner resists the urge to neatly package Bourdain’s life and death as well. It is a bold move, in accord with Bourdain’s example, and it’s undercut only slightly by the statement that this is what “Tony” would have wanted. If the preceding two hours had taught us anything, it’s that we shouldn’t presume about what Anthony Bourdain desired. He thrilled to challenge the expectations of everyone he loved, worked with, and entertained. Like all of us, we are fully known not even to ourselves. We are known fully only to the One we meet beyond the veil. I pray Tony was well met.

Elijah Davidson is Co-Director of Brehm Film and Senior Film Critic.

Ruth Schmidt reviews a documentary about the landmark concert no one has been talking about for sixty years.